November 19, 2012 — In Bangladesh, workers wade into muddy, parasite-infested waters near the Sundarban mangrove forests to catch baby shrimp that will later be processed for export. Elsewhere in rural South Asia, they toil in locked buildings, weaving luxury carpets on filthy, ramshackle looms.

These workers, many of them children, often work 14 or more hours a day. They are bonded laborers—essentially, slaves.

According to Siddharth Kara, six out of every 10 slaves in the world—between 18.5 and 22.5 million people—are bonded laborers. Kara, a fellow on forced labor at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) and a fellow on human trafficking at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, says these slaves work in a wide range of industries: rice, tea, frozen fish and shrimp, carpets, cigarettes, fireworks, construction, brickmaking, minerals and stones, gems, and apparel.

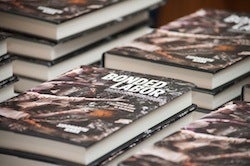

An expert on contemporary slavery, Kara read from his new book, Bonded Labor: Tackling the System of Slavery in South Asia, and answered questions at a reception celebrating the book’s publication, at HSPH on November 7, 2012. The new book is the second of three Kara is writing about modern slavery. The first, Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery, was named co-winner of the prestigious 2010 Frederick Douglass Award at Yale University for the best nonfiction book on slavery.

Bonded laborers: always in debt

Bonded laborers are those who wind up working in highly exploitative conditions for years and years trying to repay debts—for food or shelter or personal emergencies—to those who provide the credit in exchange for pledged labor. Paid meager wages, and often charged exorbitant interests rates and assessed myriad penalties, they can never make enough money to pay back their debts. Their bondage can pass from generation to generation; if a person can’t work off a debt during his lifetime, it gets passed on to his children.

Bonded labor is considered a form of slavery that is prohibited both by international conventions and the domestic laws in several South Asian countries. Yet the practice persists because of poverty, absence of alternative credit sources for the poor, a lack of justice and rule of law, and social acceptance of the exploitation of minority castes and ethnicities that has been prevalent in South Asia for hundreds of years. According to Kara, the bonded labor system generates billions in profits every year.

“You’ve got social acceptance of the condition that these people often find themselves in,” Kara said in an interview. “There’s a refrain through South Asia that the alternative—destitution, homelessness, or forced prostitution—might be worse for people. But that’s not a good enough reason not to do anything. It just means we have to provide a better alternative.”

Another big reason that bonded labor persists is that global industry continues to demand low-wage workers, Kara said.

To conduct his research on bonded labor, Kara traveled throughout South Asia and beyond, interviewing and comprehensively documenting the cases of more than a thousand former and current slaves of all kinds. He has witnessed firsthand some of the deplorable and violent conditions in which slaves work. At times, when he attempted entry into factories where he suspected there were bonded laborers, he was turned away at gunpoint.

How to fight bonded labor

In his book, Kara suggests a number of ways to decrease the prevalence of bonded labor, such as ensuring that employers meet minimum wage requirements for poor workers; strengthening laws regarding bonded labor and punishing exploitative employers more severely when they break the law; and providing support and training to help people get out of bonded labor.

“In the book I call for a transnational forced labor and bonded labor intervention force,” Kara said. “I envision hundreds of trained law enforcement officials with a specific mandate to find, identify, liberate, and re-empower these individuals—and to punish the exploiters.”

Also key, Kara said, is getting the word out, based on reliable data, about all of the products that are tainted by bonded labor. “We have to trace the supply chains of many of the products produced by bonded laborers—the carpets, the rice, the shirts—and quantify the extent to which they’re tainted,” Kara said. “For instance, roughly a third of the hand-woven carpets coming from South Asia are tainted by child labor and bonded labor. The biggest market for these carpets is the United States. So you take that information and leverage it into consumer awareness campaigns, industry pressure campaigns and, at the top level, government-to-government negotiations.”

photo: Aubrey LaMedica