February 26, 2013 — A small girl in Tanzania is getting ready to go to sleep. She is tucked safely in her bed, surrounded by mosquito netting. “Hey mosquito, I hear you, but you can’t get at me,” she says. “My net is treated.”

The girl is featured in a short video clip that’s part of Sesame Workshop’s “Kilimani Sesame” show, produced specifically for Tanzania. The goal is to fight malaria, which each year kills roughly 60,000 in the African country—80% of them children.

Explaining the importance of using mosquito netting treated with insecticide is an example of the kind of health promotion message that Sesame Workshop—the nonprofit that created the children’s public television show “Sesame Street,” featuring Muppets like Elmo, Cookie Monster, and Big Bird—disseminates in locations from Nigeria to Northern Ireland. This and similar efforts were the subject of a February 12, 2013 talk at Harvard School of Public Health by Abigail Bucuvalas, Sesame Workshop’s assistant director of global education. The talk was part of the Health Communication Concentration Speaker Series.

“There’s an enormous number of health issues that we could try to address around the world,” Bucuvalas said. “More and more, we’re seeing that many of the developing countries we work in have a double burden of disease. Infectious diseases like HIV and malaria are still a problem, but increased access to high-calorie foods and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle are causing increases in diabetes and obesity as well.

Since “Sesame Street” first aired in 1969, its producers have promoted early childhood education. They’ve also aimed to include positive messages about health, Bucuvalas said.

Different countries, different messages

Today, there are more than 20 versions of “Sesame Street” that reach millions of children, and Sesame Workshop has a presence in more than 150 countries. Show producers develop messages about health, education, and development specific to each country, Bucuvalas said. For instance, in South Africa’s “Takalani Sesame,” there are segments about HIV/AIDS; in India’s version, “Galli Galli Sim Sim,” there are confident, strong female characters, to broaden young girls’ sense of life’s possibilities; in areas where there’s been conflict, such as Northern Ireland and the Middle East, shows emphasize respect for and understanding of others—even if they come from different backgrounds.

In general, Sesame Workshop works outside the U.S. when invited by a government, nongovernmental organization, or foundation, Bucuvalas said. Shows in each country are locally produced with input from educators and health workers, and health segments are tested on small groups of children for effectiveness. Depending on the country, Sesame Workshop provides whichever forms of media are the most helpful—videos, books, pamphlets, fliers, public service announcements, or digital or mobile phone content.

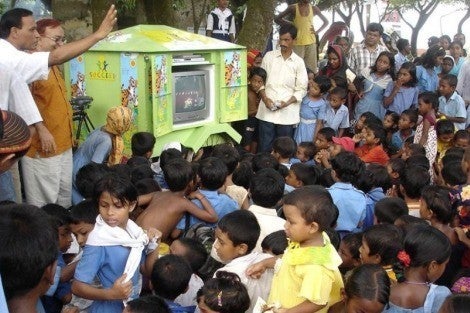

For example, in Bangladesh—where much of the population doesn’t have access to electricity—episodes of “Sisimpur” are shown from a traveling rickshaw outfitted with video equipment.

In the U.S., one focus of “Sesame Street” has been battling the obesity epidemic. Bucuvalas played a short segment for audience members that showed First Lady Michelle Obama talking with Elmo about healthy eating and exercise. Cookie Monster—who in the past ate cookies pretty much all the time—has been “tweaked,” Bucuvalas noted. “Cookie Monster now eats fruits and vegetables most of the time and every once in a while gets a cookie treat.”

photo: TM and © 2013 Sesame Workshop. All rights reserved.