To thousands of Americans stricken with polio, it was a miraculous life saver, making it possible to breathe despite paralysis.

To Harvard School of Public Health professor Philip Drinker, it was that “damn machine,” the almost accidental invention that defined his legacy.

Drinker was in his mid-30s, an assistant professor in the Department of Ventilation and Illumination at the emerging Harvard School of Public Health, when he hit upon the idea of using a respirator on polio victims. The spark for the idea was serendipitous: Drinker had been called to Children’s Hospital to consult on a topic within his field of expertise—a drop in temperature in one of the air-conditioned rooms for premature infants—when he was horrified by the sight of children in polio-induced respiratory paralysis. “He could not forget the small blue faces, the terrible gasping for air,” his sister, the renowned biographer Catherine Drinker Bowen, wrote in her memoir Family Portrait.

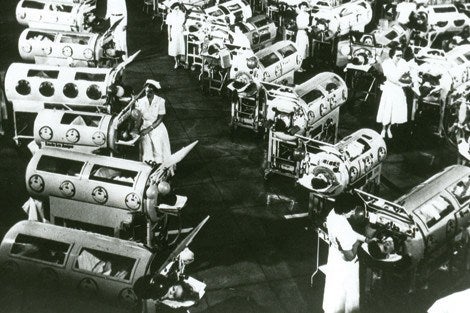

While saving the lives of polio victims wasn’t something he’d ever set out to do, Drinker put his mind to the challenge. The breathing apparatus known as the Drinker respirator—later dubbed the iron lung—underwent its first clinical trial at Children’s Hospital on October 12, 1928 on an eight-year-old girl. On the brink of death due to respiratory paralysis, she began to breathe normally within seconds of being placed in the machine. These dramatic results brought overnight fame to Drinker—the younger brother of HSPH Dean Cecil Kent Drinker—and when a polio epidemic swept the northeastern United States several years later, demand for the device skyrocketed.

For all the fanfare, Drinker was always somewhat chagrined about the fanfare surrounding an invention that had come about by chance. “As time passed, Phil began to look on what he called ‘all the fuss about the respirator’ as out of focus,” his sister wrote. “He said that in forty years’ work at the School of Public Health the ‘damn machine’ was only one thing, and it just happened.”

Is there an event, person, or discovery in Harvard School of Public Health history that you’d like to read about? Send your suggestions to centennial@hsph.harvard.edu.