Bill and Lori Housworth uprooted their young family from Louisville, Kentucky, and moved to Siem Reap, Cambodia, to cultivate top-quality medical care in one of Asia’s most impoverished areas

By sunrise at Cambodia’s Angkor Hospital for Children (AHC), the crowd of people waiting for care had packed the waiting room and spilled out into a grassy courtyard. Many had arrived the previous night, after traveling hundreds of miles by car, motor scooter, and even oxcart to reach this hospital in the bustling city of Siem Reap, a few miles from the 12th-century Angkor Wat temple complex. Mosquito nets, borrowed from the hospital, hung over benches that people had pushed together for makeshift beds. As the morning light grew stronger, some families migrated to the hospital’s kitchen, where they cooked rice, vegetables, and a bit of fish (all donated by the hospital) into a breakfast porridge.

At 6:30 a.m., the nurses started making their way through the crowds, triaging patients. Within half an hour, it was 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and the noise had become so clamorous that one of the nurses needed a bullhorn to call out the names of those who were next in line to be seen by a doctor. The hospital’s executive director, Bill Housworth, MPH ’06, began making rounds. Tall, with short-cropped gray hair and prominent features, and walking briskly in his favored cowboy boots, Housworth paid a visit to each of the hospital’s departments.

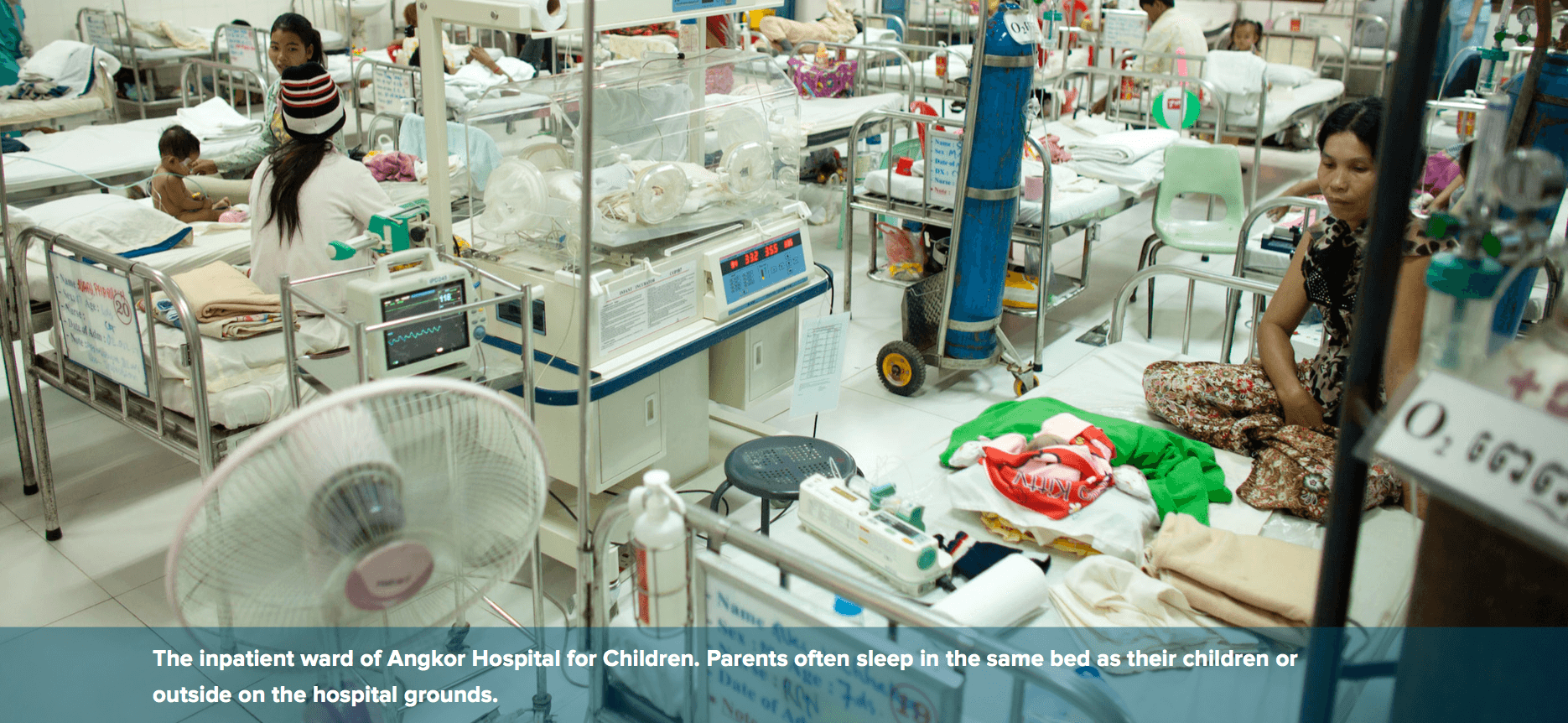

He started with the neonatal intensive-care unit, which was always full with half a dozen babies on ventilators and full life support, a level of care available nowhere else in Cambodia. Next, Housworth would check on the inpatient ward, asking the doctors and nurses there how their patients had fared overnight. Each of that department’s 40 beds was filled with a child sweating through bouts of pneumonia, receiving intravenous fluids for waterborne diarrheal illnesses, or recovering from surgery to remove cancerous tumors or repair congenital heart defects.

Known here as Dr. Bill, Housworth had moved to Cambodia from Louisville, Kentucky, with his wife, physician Lori Housworth, MPH ’06, and three small kids (a fourth would be born in Cambodia). While Lori, whose round face often manages to look both cheerful and steely-eyed, held no official title at AHC, her presence was felt everywhere—from mentoring the hospital’s young doctors and nurses to consulting on complex cases.

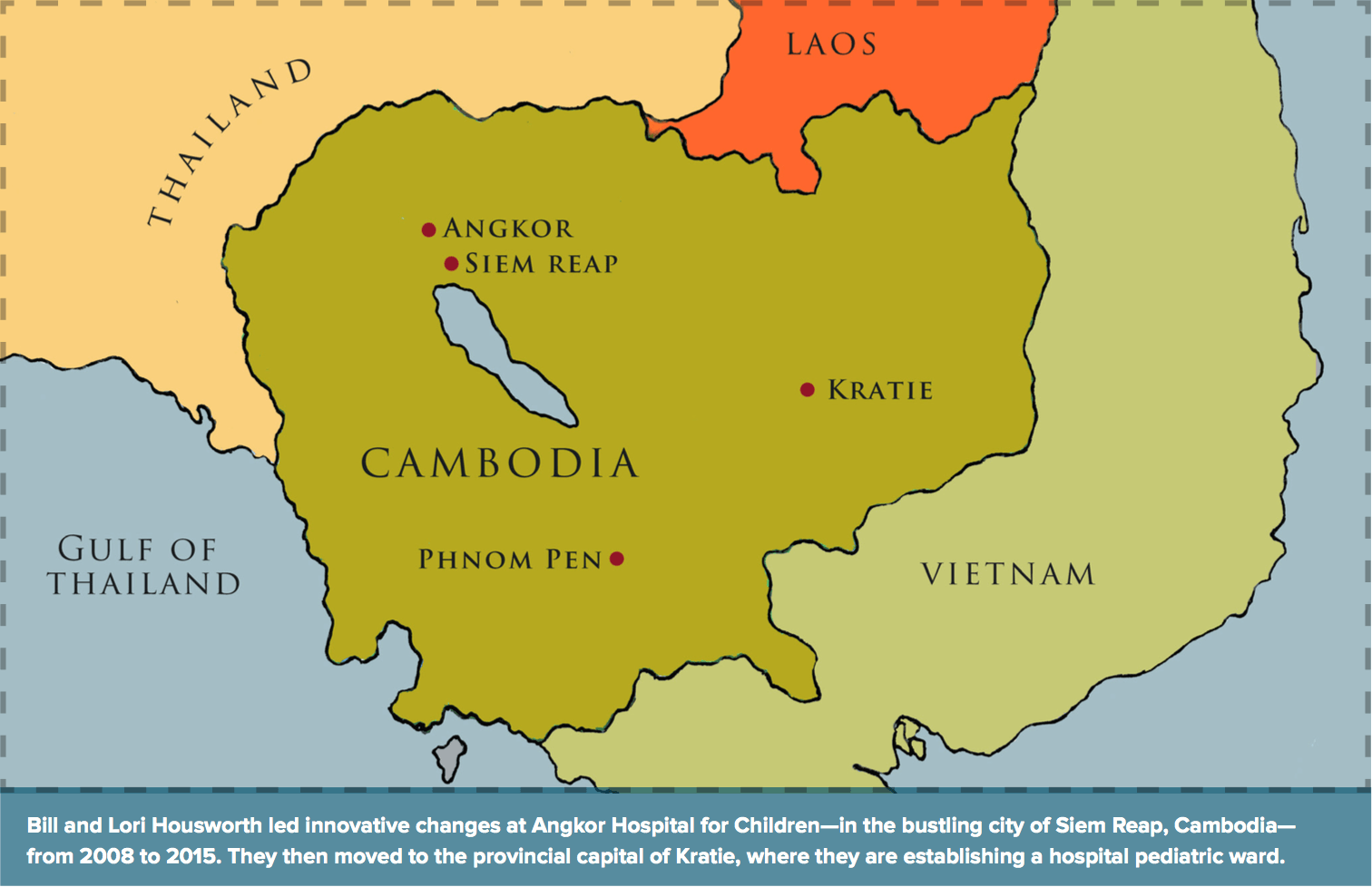

Bill led Angkor Hospital for Children from 2008 until earlier this year, when he handed the job over to Cambodian leadership and the family moved on to another hospital posting in a more impoverished area of northeastern Cambodia.

In both locales, the couple’s immediate priority has been to provide high-quality medical care to a nation in which nearly a third of the population lives on less than $2 a day, about 40 percent of children are malnourished, and the infant-mortality rate is more than five times higher than it is in the United States. And they say their time at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health prepared them for a larger mission: to empower Cambodians to achieve the same high level of pediatric medicine nationwide.

BUILDING A PREMIER PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL

When the Japanese photographer Kenro Izu came to Cambodia to photograph Angkor Wat temples in the mid-1990s, he was so moved by the many children he met who were stunted by malnutrition, disfigured by birth defects, and mutilated by land mines that he committed himself to building a pediatric hospital for Cambodia. He started a nongovernmental organization (NGO) called Friends Without a Border, which raised money for a dedicated medical facility.

AHC opened its doors in 1999 as a small outpatient facility. It has grown into Cambodia’s premier pediatric hospital, with units dedicated to emergency care, inpatient treatment, neonatal intensive care, physical therapy, and surgery, among others. It is also Cambodia’s only pediatric teaching hospital, training the country’s next generation of doctors and nurses.

The most common ailments here—tuberculosis, malnutrition, cholera, and insect-borne tropical diseases such as malaria and dengue fever—are often linked with poverty and a lack of basic amenities, such as clean water. Yet many children come here with complicated needs: heart surgery, long-term cancer care, or antiretroviral treatment for HIV/AIDS. Every day, about 450 new patients, ranging in age from newborns to teenagers, arrive at AHC, where the care is free for those who cannot pay.

“To be able to serve and to see the world through the eyes of people who have been through more than we can imagine, who have suffered more than we can imagine—for us, it’s been a huge blessing,” says Bill. “The strange thing is that you will never fit in again where you come from. And that’s OK. We don’t completely fit in in Cambodia or back in the States. But in exchange, we’ve had an experience that is deeper than words can describe.”

A SENSE OF DOOM

One recent evening, while driving back to Siem Reap from a medical conference in the city of Battambang, a Cambodian colleague remarked to the Housworths, “You see that sunset you expatriates think is so beautiful? For us, the older Cambodian generation, even the most beautiful of sunsets still bring us a sense of doom, for that is when the killing always began.”

From 1975 to 1979, Cambodia endured the genocidal rule of the Khmer Rouge, a radical regime that tried to impose a Communist, agrarian-based society and killed millions, specifically targeting doctors and other educated people, whom they suspected were “counter-revolutionary.” Years of civil war had preceded the Khmer Rouge rule, and while a Vietnamese invasion toppled them from power, the Khmer Rouge persisted as an insurgency well into the 1990s. Cambodia still suffers the legacy of that terror, rampant destruction, and mass murder. It is one of the poorest Southeast Asian nations, with the lowest levels of literacy and life expectancy and highest rates of infant mortality.

When the fighting ceased, there were only a few dozen doctors in the entire country who had not fled or been murdered. Hospitals had been leveled; medical supplies were virtually nonexistent. The public health fallout from years of devastation includes tens of thousands of children and adults maimed by the land mines and unexploded bombs that remain hidden in the countryside, rampant posttraumatic stress, and a childhood malnutrition rate of 40 percent.

The Khmer Rouge’s bloody legacy also left a less-visible mark on Cambodia’s public health, says Bill: it sowed a pervasive mistrust. “If you lived through something like the Khmer Rouge—where your survival depended on lying, and you knew that everyone else was lying—that mindset lives on,” he says. This deep unease keeps medical staff from different hospitals from communicating about a patient’s medical history. It also deters Cambodians from seeking routine medical care, even for ailing newborns. As a result, the essence of public health—preventing diseases before they take hold—is undermined.

A MARRIAGE ROOTED IN ADVENTURE

The Housworths didn’t know about AHC when they first visited Cambodia in 2001. They came for a short stint of volunteering with an NGO focused on clean water and sanitation. They had married a year earlier, following a courtship that began during their medical residencies at the University of Louisville Hospital.

“To do this kind of work, you have to be adventurous. That was the quality that initially drew us together,” says Lori. Cambodia was just the most recent in a series of international volunteering trips the Housworths had made, individually and as a couple, often to clinics and disaster-relief efforts in impoverished places such as Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.

These overseas assignments taught the couple that the grief of a parent over a dying child transcends borders—the only difference being that in the developing world, the children often don’t stand a chance of survival.

“We’ve both always had the desire to live our lives outside the box,” says Lori. “Bill is the visionary, and I am good at laying out the details of a plan to make it happen.”

Their first trip to Cambodia convinced them that if they wanted to have a lasting impact, their physician training wasn’t enough. “The medical challenges in Cambodia were really public health challenges,” says Bill.

Most Cambodians lived in rural areas without reliable access to clean water, electricity, or routine medical care. Like many of the places the Housworths had volunteered in, Cambodia relied heavily on NGOs and couldn’t train its own doctors and nurses in sufficient numbers, because the medical and educational infrastructure had been gutted by the Khmer Rouge.

So the Housworths shifted their goal from delivering front-line care to helping developing nations build their own robust health care systems. That led them, in 2004, to Harvard Chan. They moved their young family into a tiny Beacon Hill apartment and focused on humanitarian studies and international health. Supporters from their evangelical church in Louisville covered their tuition.

LEARNING LEADERSHIP AT HARVARD CHAN

Bill and Lori say what made their education at the School unique was how it taught them leadership skills—not just to understand disease from a public health perspective but also to work with NGOs, funders, and government officials to improve conditions. “Lots of public health schools can teach you epidemiology and statistics,” says Bill. “But only a place like Harvard can combine that hardcore knowledge with the worldly wisdom that allows you to step out and accomplish something.”

At Harvard, he learned how donor funding and donor control work in the public health sphere. Bill quotes a biblical phrase to explain what he means. “You must be wise as a serpent, yet innocent as a dove,” he says, “which means that to make the right thing happen for the people you are there to serve, you have to understand that others may not have the best motives. On the other hand, you personally have to have the best motives. You have to keep your own motives pure, even when working with the power structures around you.”

For example, some of the outside medical institutions that partnered with AHC pushed for high-end diagnostic tests that weren’t needed at the hospital. Other institutions offered what Bill calls “quid pro quo arrangements” that clearly benefited them more than AHC. And occasionally, foreign medical researchers tried to skirt the ethical restrictions of their home countries by testing unproven treatments at AHC or sought Cambodian patient data for their own research while offering little funding or training for AHC staff in return.

“Setting priorities for the organization from the Cambodian leadership perspective, and sticking to those priorities despite outside pressures to drift, were some of the most important things we did,” Bill says.

A year after graduating, the Housworths learned about the executive director opening at AHC, and Bill decided to apply. The decision wasn’t easy. Both Lori and Bill had well-paying jobs in Louisville hospitals. They also had three young children. Most of their medical colleagues thought the idea of moving halfway around the world was reckless.

A CHOICE TO NOT BE SAFE

Bill understood the doubts. He felt them himself. “My wife has always had more faith than me,” he says. “I remember the night that I finished my last shift in the emergency room in Louisville. I went over to our little house that

we were giving up in order to take some final objects and boxes out of it. I was there, alone, late at night. I remember falling to my knees in the upstairs bedroom that didn’t have any furniture in it anymore and crying. I cried hard, thinking, ‘What am I giving up? Why am I relinquishing a successful practice, security, and a known future for something that is very, very risky—careerwise, safetywise, and possibly from my children’s perspective?’”

But for Lori, the choice was obvious. “We could play it safe, put our children in the best schools, and maintain our comfort and security. Or we could step out in faith and try to make a difference. I kept remembering a mother I had met in Cambodia. She had been removed from her shanty along Lake Tonle Sap and transported to a relocation area with no water and no sanitation. She lived in a tent in a dry, dusty field. One day she brought me her baby, who was sick with pneumonia, to see if I could help. Her face stayed in my mind. Certainly she and her family were not ‘safe.’ In the end, we did what we were called to do.”

Once the couple began working in Cambodia, Lori continues, the everyday risks became more apparent: “A snake in the kitchen, dangling power cords everywhere, filthy water flooding our neighborhood during the seasonal monsoons, a man raising crocodiles in the backyard of the house we were renting. You quickly realize that life is not fully under your control. But that’s true no matter where you are.”

CONFRONTING CULTURAL TABOOS

Among her responsibilities, Lori oversaw the hospital’s sexual abuse clinic. Child sexual abuse is epidemic in Cambodia, yet Cambodian physicians are uncomfortable talking about it. That reticence reflects not only a taboo around the problem itself but also the lack of rule of law in Cambodia, which causes physicians to be worried that their own practice or reputation could become quickly impugned by becoming involved in sexual abuse cases. Sometimes, such cases involve powerful families, leading to a “tit-for-tat accusation game,” in which kin of the accused claim that clinicians are taking money from the accusers or are simply incompetent, says Lori. Cambodia is also a popular destination for sex tourists who target children. And many cases of abuse involve older children, often teenagers, who harm younger relatives when left on their own by parents who must travel long distances, sometimes out of the country, to find work.

Lori recalls a 7-year-old girl whose mother was away working in Thailand and who was left in the care of her grandmother for months at a time. The grandmother also cared for a teenage grandson whose parents had died in an accident.

“They lived in a tiny hut, and the grandson and the 7-year-old slept in the same bed. And this is where the abuse occurred,” Lori says. “So many medical problems we see stem from difficult social situations born of dire poverty. Addressing the immediate medical needs is always tied to addressing the underlying social challenge.”

With the help of several engaged donors, the Housworths established the first hospital-based social-work program in Cambodia, training social workers and clinicians to spot and refer sexual abuse cases. In turn, AHC became a nationally recognized center for the detection and prevention of sexual abuse.

RAISING THE STANDARD OF CARE

During the Housworths’ tenure, AHC added a cancer care center and an ophthalmology center. The hospital also opened a much-needed heart surgery unit, after the Housworths realized that a large number of Cambodian children with easily mended congenital heart defects were going untreated, suffering prolonged illness, and frequently dying. In 2008, when the Housworths arrived, the hospital was able to diagnose heart conditions in patients but couldn’t provide the corrective surgery.

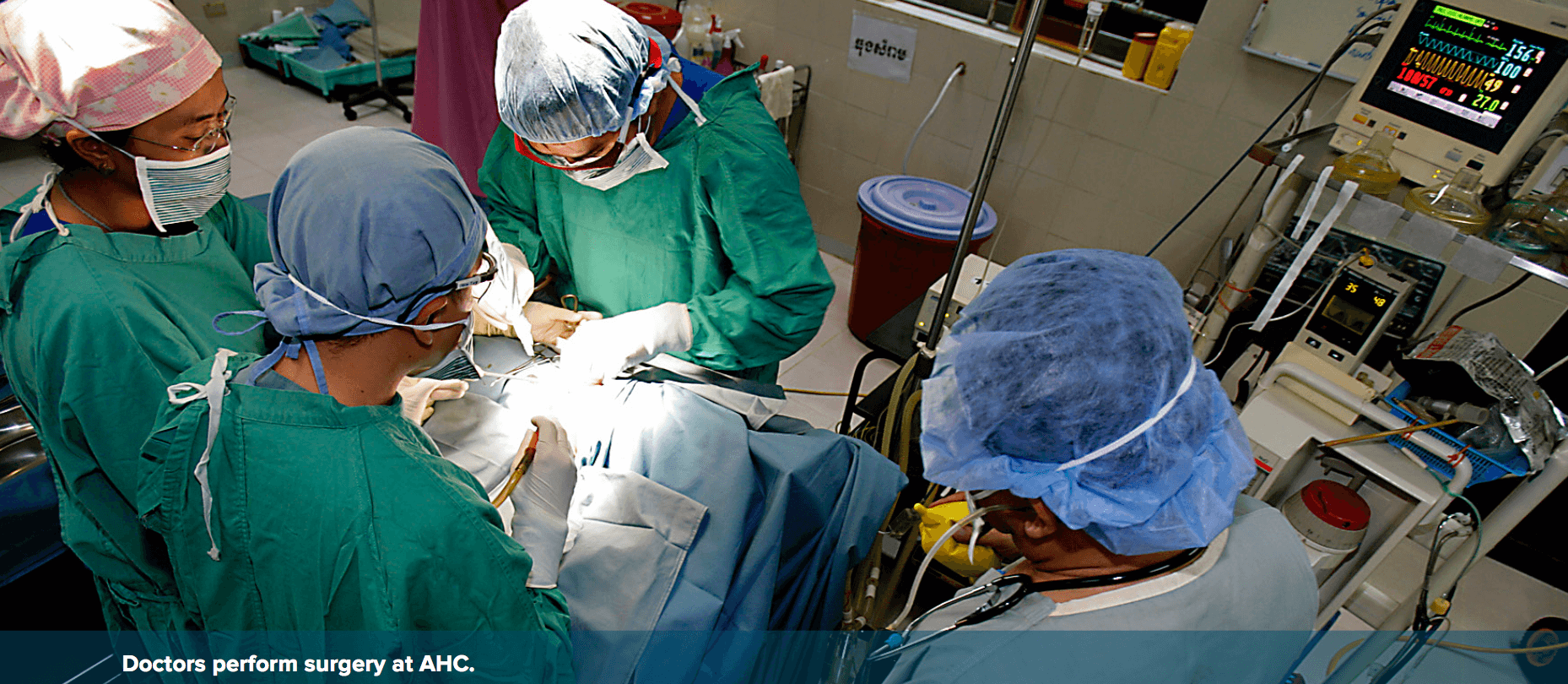

With the assistance of donors and hospitals in Singapore, Australia, and the United States, the Housworths built a treatment program for congenital heart disease. At first, all the operations were performed by visiting foreign surgeons. But by 2013, Cambodian surgeons were doing open-heart surgery unassisted—more than 100 operations per year.

The Housworths have also devoted much of their work to setting up systems—such as mortality reviews and transparent audits of hospital finances—as models for other Cambodian medical institutions, despite a culture where hiding mistakes for fear of blame and harsh retribution was common.

In 2011, AHC opened a satellite clinic on the grounds of a Cambodian government hospital, in a poor province about 20 miles from Siem Reap. The clinic became the government hospital’s de facto pediatric ward, treating more than 1,000 children a month. It is also a springboard for the hospital’s community health development project, which trains village volunteers to improve local knowledge of nutrition, sanitation, and hygiene and distribute needed supplies such as water purification filters.

GOING ABROAD FOR SPECIALIZED TRAINING

Every year, the hospital also sends a handful of doctors and nurses abroad for specialized training. In 2014, that group included Prak Manila, a registered nurse and the chair of AHC’s local board of directors. Manila was born in Phnom Penh in 1970, the daughter of two nurses. The Khmer Rouge killed two of her brothers, and the rest of the family narrowly escaped.

Manila started working at AHC in 1999. “At the time, 60 percent of the staff were foreigners and there were no Cambodians in leadership,” she says. Today, the only foreigners working at AHC are visiting surgical specialists.

In 2011, AHC sent Manila, initially trained as a midwife, to Bangkok, Thailand, to earn her bachelor’s in nursing, and then again in 2014 for a two-year master’s program in nursing administration. More recently, Manila’s work has focused on training nurses in community clinics and government hospitals rather than direct patient care, helping carry out the vision of AHC as a force for bolstering Cambodia’s homegrown health care system.

“Dr. Bill is a great leader,” Manila says. “He empowered people. He encouraged people to take risks. I’ve become a more creative thinker and more independent because of him. He motivated me to be a leader.”

CEREMONY AND SENSITIVITY

The Housworths, in turn, have been transformed by Cambodia. “I’m an emergency room doctor,” says Bill. “By nature, I’m kind of gruff, and I’m usually thinking about what the solution is or what the next move is. But in a Buddhist culture, and really everywhere in Cambodia, ceremony is very important, and so is being sensitive to what another person is feeling.”

For example, he says, “I wear cowboy boots and I move fast. That shows that I value time and doing things.” But when his good friend Thir Kruy, the secretary of state for Cambodia’s Ministry of Health, asks Bill to join him for dinner, they have lingering conversations about the challenges facing Cambodia. “Kruy doesn’t value time as much as he values relationships,” says Bill. “When I slow down and talk to him in a relaxed setting, that’s when we get things done.”

THE NEXT CHALLENGE

At the end of each day at AHC, families of patients whom the staff could not treat settle in for a night in the courtyard, cooking dinner in an outdoor kitchen and lying on mats under hospital-provided mosquito nets. “Some of them like sleeping in a place like this even better than their own house,” says Manila. “When I walk through there, I can feel a sense of comfort and happiness.”

The Housworths’ ultimate goal was always to help AHC transition to a fully Cambodian staff providing world-class pediatric care. And under their leadership, as the hospital’s training programs took hold, the number of foreign doctors and specialists dwindled. In 2013, Friends Without a Border at last handed over hospital operations to a Cambodian NGO.

This past February, the Housworths moved on to a new challenge: replicating the AHC model in northeast Cambodia, the poorest region of the country. With the support of the Cambodian Ministry of Health, they aim to create a pediatric ward at the hospital in Kratie, a provincial capital on the Mekong River, not far from Cambodia’s border with Laos. There, says Bill, “the neonatal mortality is five times higher than it is in Phnom Penh. It’s 40 times higher than it is in a place like Singapore.”

Once again, the Housworths’ plan is to train, educate, and build up a system of compassionate care that can eventually be handed over to Cambodian doctors and nurses. “So many times, wealthy international donors look at Cambodia and they see it as a poor place that simply needs a handout,” Bill says. He concedes it could take another 10 years for the Kratie facility to become self-administering. “But Lori and I see ourselves here long-term. We believe in Cambodia and Cambodians.”

Chris Berdick is a Boston-based science journalist. Follow him @chrisberdik.

Photos: Sam Chamroeun/ Angkor Hospital for Children; Bernice Wong