Tackling two-tier health care

With the creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965, the United States began its first large-scale experiment with a formal national health system. Almost overnight, it began subsidizing medical care for the elderly and poor. But for Alonzo Yerby, who served as a consultant to the Johnson administration during the drafting of the legislation, the policy didn’t go far enough.

“Health care for the disadvantaged … tends to be piecemeal, poorly supervised, and uncoordinated,” he wrote in an address to the White House Conference on Health in January 1966, six months after the legislation was passed. “We can no longer tolerate a two-class system of health care.”

Yerby, who later became head of the HSPH Department of Health Policy and Management, remained troubled by the social injustice he saw within medicine. Creating a successful national health system, he felt, had to begin with addressing the day-today issues of people living in poverty.

An effective health service must “strike not at the symptoms, but at the causes of the health crises of our metropolitan areas,” he wrote in 1965, setting the tone for his tenure at Harvard. “The social environment of the individual … influences his health and potential for recovery from disease.” Providing quality preventive care was essential, in Yerby’s eyes. So too was access to doctors, since long waiting times and frequent travel between specialists placed a heavy burden on the poor.

Yerby died in 1994. His passion for equity and social justice in public health is perhaps his greatest legacy. During his 16 years on Harvard’s faculty, he inspired legions of students and left a lasting impression on his peers—and on his son, Mark, who followed in his father’s footsteps by earning an MD and MPH, and now maintains a private neurology practice in Portland, Oregon, where he adheres to the key principle of his father’s work. As Mark told Harvard Public Health Review in 1997, “He believed that public health was not just the purview of health professionals, but belonged to every physician.”

Bridging AIDS and human rights

Jonathan Mann, physician and advocate, pragmatist and visionary, transformed the way the world looked at AIDS. As the first head of the Global Programme on AIDS for the World Health Organization (WHO), he illuminated the intersection of health and human rights. Mann joined the HSPH faculty in 1990 as a professor of epidemiology and international health. He became the first director of the School’s François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights, which he founded in 1992 with the Countess Albina du Boisrouvray, whose generous $20 million gift made the center’s work possible. Mann died at age 51 in 1998, in the crash of Swissair Flight 111.

In his leadership post at the WHO from 1986 to 1990, Mann forged the approach to AIDS now considered axiomatic: prevention, understanding the social and behavioral dynamics and patterns of sexual transmission, comprehensive surveillance, monitoring, and education, a robust program of biomedical research, and an emphasis on the rights of the individual.

Today, as AIDS becomes a treatable chronic disease in many parts of the world, it is easy to forget the point at which a conscious decision was made to embark on what the Village Voice described as “a condom-based compassionate strategy to slow the spread of AIDS,” instead of opting for the repressive quarantine strategies that had many supporters. Mann “had an edgy agenda and an edgy analysis,” said Jennifer Leaning, the current director of the FXB Center. “He was critical of the pace of progress.”

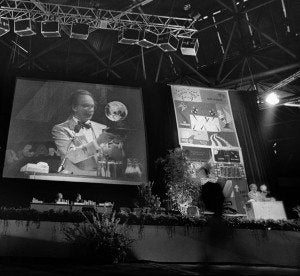

As Mann himself told the Second International Conference for Health and Human Rights, at Harvard University in 1996, “The tectonic plates are shifting, but it is at the intersection of health and human rights that the most radical transformation is occurring, and it is there that the future will lie.”

More than 20 years after her gift, the Countess’s passion hasn’t waned. She remains an active presence in the work of the FXB Center and related activities around the world. “There’s so much to do,” she said. “But as I look at the women and children on field trips, I get the energy to go on.”