Quick Links

Research with real-world impact

Our faculty and students work together to uncover the drivers of health, disease, and inequity — and develop powerful solutions.

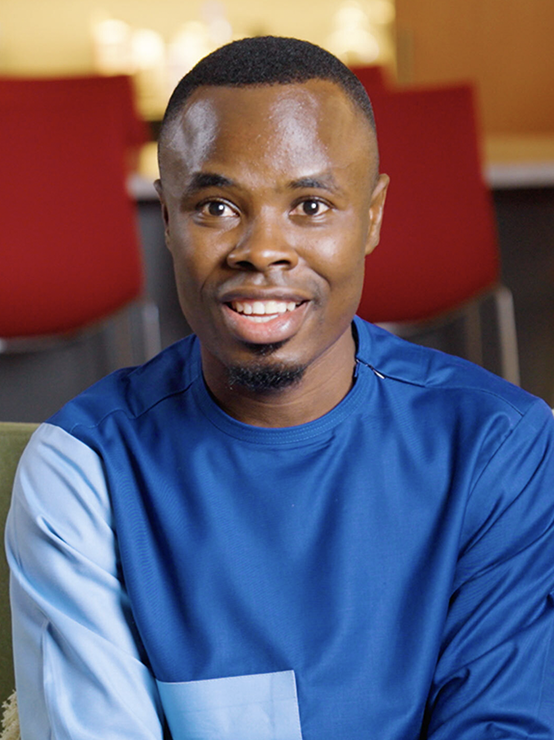

A student experience to match your goals.

Truly global community

Join a powerful network of 16,000+ alumni, including global leaders in health policy, practice, and advocacy at the highest levels.

Programs on campus, online, and in the field

Choose from 35 degree programs and over 150 executive education classes to fit your schedule. Apply your learning in the field with hands-on research and practicum opportunities in dozens of countries.

Accessible faculty and dedicated mentors

Learn from world-class scientists and practitioners, including nearly 500 faculty and more than 100 research scientists. Find mentors who will support you, challenge you, and open doors for you in every field of study.