Pinpointing Office Worker Exposures to Chemicals in their Office Buildings in 4 Countries by Using Silicone Wristbands

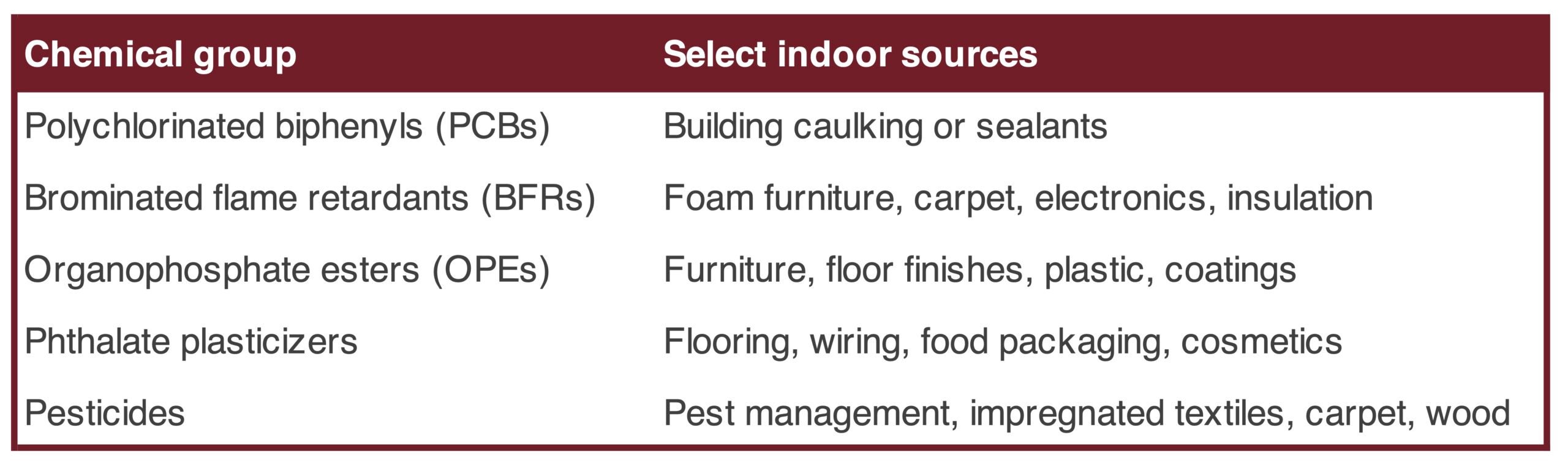

Every day, we are exposed to mixtures of hundreds of chemicals that are present in the materials and products that surround us in our buildings (Table 1). For example, semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) build up in indoor dust and air and get into our bodies through ingestion, breathing, and direct skin contact. Typical office workers spend about one quarter of their week inside office buildings, where SVOCs are often detected at higher levels than in homes. Certain SVOCs are associated with a wide range of health effects including infertility, poor pregnancy outcomes, impaired brain development, thyroid disease, and cancer.

Why silicone wristbands?

Scientists have traditionally relied on blood and urine tests (or “biomonitoring”) to measure chemicals in our bodies. Yet, these tests are often expensive and invasive, and they can’t distinguish between chemicals that get into our body from external sources (such as buildings) versus internal sources (food and drink).

Recently, an old wearable has gained renewed popularity as an alternative sampling tool. Enter silicone wristbands. These are the very same bands made popular by Lance Armstrong’s LiveStrong bracelets. Researchers found that the silicone in the bands traps the chemicals the wearer comes into contact with from air, dust, and products.

The Harvard Healthy Buildings Program recently completed a first-of-its-kind study that used silicone wristbands to pinpoint external exposures to chemicals in the office workplace. We were able to instruct office worker participants to wear their silicone wristband only at work in their office building for four workdays.

What did we find?

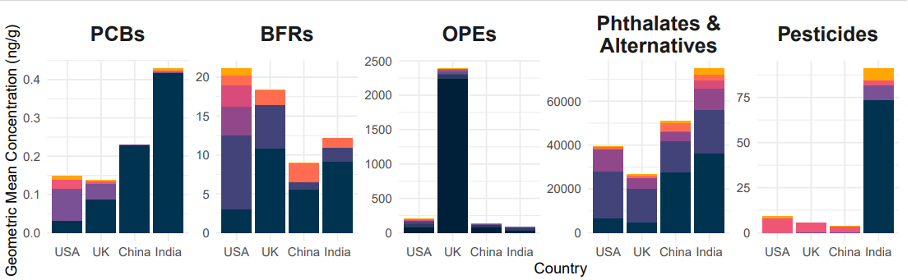

The study included 251 participants across four countries – the USA, UK, India, and China. Exposures were vastly different by country, often reflective of differences in regulations. Ultimately, our findings were concerning enough that we recommend immediate action to reduce indoor chemical exposures to office workers.

Key takeaways:

- Though certain dangerous chemicals, also known as “legacy chemicals,” have been banned or eliminated for decades, we still found measurable amounts in the wristbands of office workers. This was especially evident for office workers exposed to PCBs and certain phased-out BFRs.

- Chemicals restricted or banned in one country are not always banned in other countries. For example, exposures to DDE (a pesticide) were much higher in India, the only country in the study where the parent chemical has not been banned.

- Phased-out chemicals are frequently replaced with similar, and sometimes more harmful, substitute chemicals. We found widespread exposures of office workers to emerging flame retardants and plasticizers used to substitute the traditional chemicals.

- Some regulations, such as stringent flammability standards for foam furniture, have encouraged the use of harmful chemicals. There were higher exposures of office workers to certain flame retardants in countries with these historical standards.

- Office worker exposures were influenced by country, building, and individual level factors. For example, exposures to phthalate chemicals were related to country restrictions, building materials, and personal use of cosmetics.

This study demonstrates that silicone wristbands are an excellent tool to investigate personal exposures to chemical mixtures specifically in the indoor office environment. It also reveals a pressing need for changes in both the free market and public policy to reduce indoor chemical exposures in buildings. The very health of our workers depends on it.

The full paper can be found here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412021003524

“Chemical contaminant exposures assessed using silicone wristbands among occupants in office buildings in the USA, UK, China, and India.” Anna S. Young, Nicholas Herkert, Heather M. Stapleton, Jose Guillermo Cedeño Laurent, Emily R. Jones, Piers MacNaughton, Brent A. Coull, Tamarra James-Todd, Russ Hauser, Marianne Lahaie Luna, Yu Shan Chung, Joseph G. Allen.

Environment International, July 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106727.