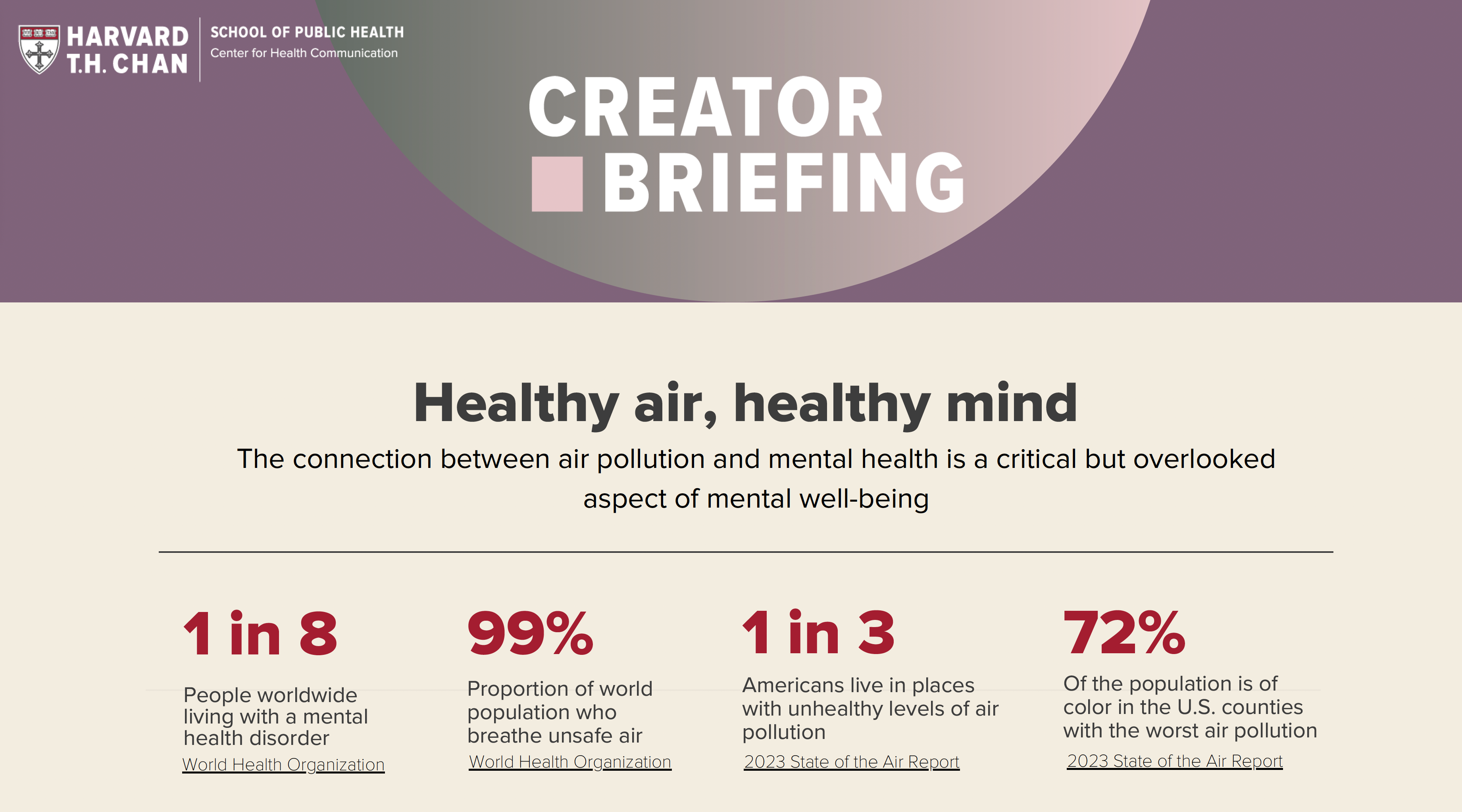

Ahead of World Mental Health Day, YouTube and the Center for Health Communications (CHC) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health held an exclusive briefing session for public health creators. The briefing focused on the overlooked connection between air quality and mental health. It was part of the center’s “Creators Summit series,” which connects scientists and creators to make sure people find evidence-based public health information on the social platforms they use every day.

“Creators know how to communicate in ways and places where people consume information. Scientists and creators must collaborate to scale information and fight misinformation”, says Dr. Joseph Allen, Associate Professor and Director of the Harvard Healthy Buildings Program. With over 45k followers on X, he demonstrates how social media can be harnessed for impactful public health communication. He has supported the CHC’s Creators Program on various occasions. “Joe sets a great example for how public health leaders can use social media to engage people with evidence-based science and policy prescriptions,” says Amanda Yarnell, senior director of the Center for Health Communication (CHC). “We’ve been thrilled to have his support for our new Creators Summit on Mental Health program.”

Co-creating evidence-based mental health information

At the CHC’s Creators Summit on Mental Health in August, Dr. Allen and other public health experts joined the conversation with mental health creators at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. In his keynote, he explained how the air we breathe impacts our mental health and well-being. Additionally, the CHC provided creators with easy-to-use content around the latest cutting-edge research. This spring, the center conducted a field trial on TikTok that showed that creators who received the toolkits were 1) more likely to produce evidence-based content about mental health on TikTok compared to those who weren’t exposed to the information and 2) more likely to share content on mental health. The New York Times highlighted the CHC’s creators program and research: “Harvard Cozies Up to #MentalHealth TikTok.

Hoping to give more creators access to these supports, the CHC and YouTube hosted a virtual creator briefing session and provided a companion toolkit ahead of World Mental Health Day in October. In this exclusive briefing, Joseph Allen and Sasha Hamdani, board-certified psychiatrist and mental health creator, delved into the connection between healthy air and healthy minds. At the Project Healthy Mind’s World Mental Health Festival in New York City, they continued the conversation on stage and live on Sasha’s TikTok, leaving the audience with simple steps to ensure that the air we breathe supports our mental health and cognitive function.

These initiatives underscore the immense potential of collaborations between scientists and creators for public health communication. Trusted and watched by millions, creators working on TikTok and other social media platforms play a critical role in ensuring individuals have access to the health information they seek. Collaborating with creators helps researchers to deliver their message to a broader audience through formats that resonate with people. In the Harvard Public Health Magazine, Sasha Hamdani shares how she became invested in social media: “Initially, I felt it was undignified for a physician to be on TikTok. Now I recognize that the public needs more people to share engaging but research-backed information in an environment not completely saturated by doctor hubris.” During the creator briefing session, she emphasized that since she met Joseph Allen at the Mental Health Creator Summit, she has incorporated (indoor) air pollution into her psychiatric screening.

Healthy air for healthy minds: What the science says

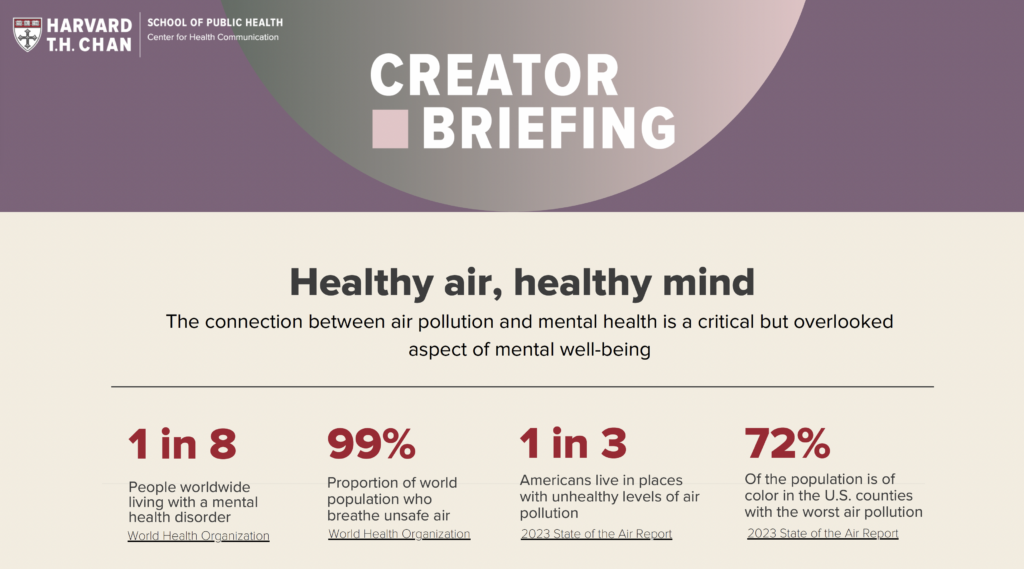

Many people know the effects of outdoor air pollution on heart and lung health. But fewer are aware that the air we breathe impacts our brain and mental health. One key component to measure outdoor air pollution is PM2.5, which is airborne dust. PM stands for “particulate matter.” 2.5 refers to particles 2.5 microns and smaller. Size matters because these small particles can reach the deepest parts of our lungs, causing local and systemic inflammation and oxidative stress [1] [2]. They find their way to our brain through the olfactory nerve and can enter brain tissue directly [3].

Research shows that long-term and short-term exposure to air pollution can have profound and enduring negative effects on mental health. Scientists found that exposure to high levels of air pollution in the past five years can lead to decreased quality of life and an increased risk of depression and suicide ideation [4]. Breathing unhealthy air is also associated with increased anxiety symptoms [5]. Furthermore, exposure to air pollution is associated with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and autism [6] [7] [8]. Children are especially vulnerable as their brains are still developing. When exposed to poor air quality, children and adolescents are at elevated risk of bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, personality disorder, major depression, affective disorders, or suicidal ideation in adolescents and children [9] [10]. A study by the Children’s Hospital in Cincinnati saw increased hospital visits related to psychiatric issues [11].

Poor indoor air quality affects us in other ways, too. Our Global CogFx study showed that PM2.5 is associated with lower cognitive test performance [12]. Moreover, different studies found that children exposed to poor indoor air quality in schools perform worse on math and reading comprehension tests [13].

The dirty secret of outdoor air pollution

Air pollution is not just something that happens outside. Most of the outdoor air pollution we breathe, we breathe indoors. Harmful air pollutants penetrate our homes, schools, offices, and other indoor environments through open doors, windows, cracks, and crevices. Additionally, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) from our stoves and volatile organic compounds (VOC) from cleaning contaminate indoor air. With humans spending 90% of their time indoors, clean indoor air is critical for physical and mental health [14]. The good news is indoor air quality (IAQ) is manageable!

Practical steps to improve IAQ for everyone

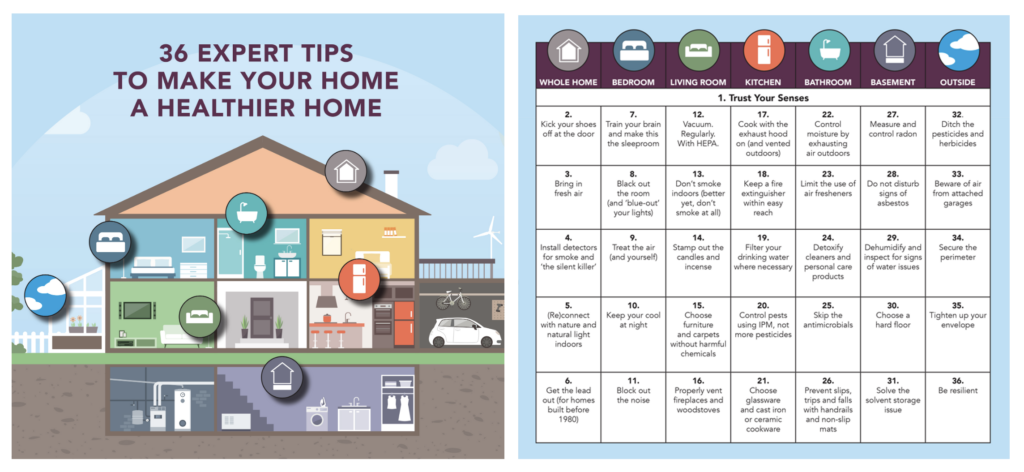

The Lancet Commission Task Force on Safe Work / School / Travel’s guidance, “The First Four Healthy Buildings Strategy Every Building Should Pursue,” suggests the following actions to create healthier indoor environments:

- Give your building a regular tune-up to avoid performance drops.

- Ensure enough clean air comes in through proper ventilation.

- Upgrade air filters to a MERV13 or better.

- Supplement with portable air cleaners where necessary

The Harvard Healthy Buildings Team created the Homes for Health Report with simple, low-cost actions that allow everyone to breathe healthier air indoors.

Furthermore, be aware of the air quality around you and check local air quality indices. Air quality monitors are affordable tools to measure the air you breathe.

Making clean air the new norm

The good news is that the topic has become a priority for the White House, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other decision-makers and standard-setting institutions. Last fall, the Lancet Covid-19 Commission released new health-based ventilation targets. This was followed by the CDC and the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), which defined new IAQ standards based on health targets. Joseph Allen sees the needle moving in the right direction: “Structural change is coming! Relevant institutions and media recognize the issue we have been discussing for years. Until now, strategies for healthy living have revolved around eating well, working out, and quitting smoking. It’s imperative to broaden our perspective and raise awareness about the impact of indoor air on our physical and mental health. Collaborating with creators helps us spread the message that healthy air matters for healthy minds.”

For more information on the impacts of air pollution on brain health, watch this discussion panel held at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health, where leading experts delve into current regulations and the latest research in this developing field.

Find more information in the companion content toolkit.

Mental Health Toolkit crafted by Healthy Buildings team members Rachel Steiner, Tomi Oyedeji-Olaniyan, Sandra Dedesko, Shivani Parikh, Lauren Ferguson, Joseph Allen, and the Center for Health Communication’s Amanda Yarnell.

Sources:

[1] O. US EPA, “Particulate Matter (PM) Basics,” Apr. 19, 2016. https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics (accessed Oct. 31, 2023).

[2] Kaimeng Liu, Shucheng Hua, Lei Song, “PM2.5 Exposure and Asthma Development: The Key Role of Oxidative Stress”, Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2022, Article ID 3618806, 12 pages, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3618806

[3] Li W, Lin G, Xiao Z, Zhang Y, Li B, Zhou Y, Ma Y, Chai E. A review of respirable fine particulate matter (PM2.5)-induced brain damage. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022 Sep 7;15:967174. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.967174. PMID: 36157076; PMCID: PMC9491465.

[4] Shin, J. Y., Park, J. Y., & Choi, J. (2018). Long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants and mental health status: A nationwide population-based cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0195607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195607

[5] Pun VC, Manjourides J, Suh H. Association of Ambient Air Pollution with Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Older Adults: Results from the NSHAP Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125(3):342-348. doi: 10.1289/EHP494. Epub 2016 Aug 12. PMID: 27517877; PMCID: PMC5332196

[6] Dementia: Zhang B, Weuve J, Langa KM, et al. Comparison of Particulate Air Pollution From Different Emission Sources and Incident Dementia in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(10):1080–1089. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3300

[7] Alzheimers, Parkinson’s and some forms of dementia: Shi L, Wu X, Danesh Yazdi M, Braun D, Abu Awad Y, Wei Y, Liu P, Di Q, Wang Y, Schwartz J, Dominici F, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Zanobetti A. Long-term effects of PM2·5 on neurological disorders in the American Medicare population: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020 Dec;4(12):e557-e565. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30227-8. Epub 2020 Oct 19. PMID: 33091388; PMCID: PMC7720425.

[8] Autism: Lin LZ, Zhan XL, Jin CY, Liang JH, Jing J, Dong GH. The epidemiological evidence linking exposure to ambient particulate matter with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022 Jun;209:112876. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112876. Epub 2022 Feb 5. PMID: 35134379.

[9] Xie, H., Cao, Y., Li, J., Lyu, Y., Roberts, N. P., & Jia, Z. (2023). Affective disorder and brain alterations in children and adolescents exposed to outdoor air pollution. Journal of Affective Disorders, 331, 413-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.082

[10] Khan, A. A., Plana‐Ripoll, O., Antonsen, S., Brandt, J., Geels, C., Landecker, H., Sullivan, P. F., Pedersen, C. B., & Rzhetsky, A. (2019). Environmental pollution is associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the US and Denmark. PLOS Biology, 17(8), e3000353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000353

[11] Cole Brokamp, Jeffrey R. Strawn, Andrew F. Beck, Patrick Ryan. Pediatric Psychiatric Emergency Department Utilization and Fine Particulate Matter: A Case-Crossover Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2019; 127 (9): 097006 DOI: 10.1289/ehp4815

[12] Laurent, J. G. C., MacNaughton, P., Jones, E. R., Young, A. S., Bliss, M. S., Flanigan, S., Vallarino, J., Chen, L., Cao, X., & Allen, J. G. (2021). Associations between acute exposures to PM2.5 and carbon dioxide indoors and cognitive function in office workers: a multicountry longitudinal prospective observational study. Environmental Research Letters, 16(9), 094047. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac1bd8

[13] Shaughnessy RJ, Haverinen-Shaughnessy U, Nevalainen A, Moschandreas D. A preliminary study on the association between classroom ventilation rates and student performance. Indoor Air. 2006 Dec;16(6):465-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00440.x. PMID: 17100667.

[14] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1989. Report to Congress on indoor air quality: Volume 2. EPA/400/1-89/001C. Washington, DC.