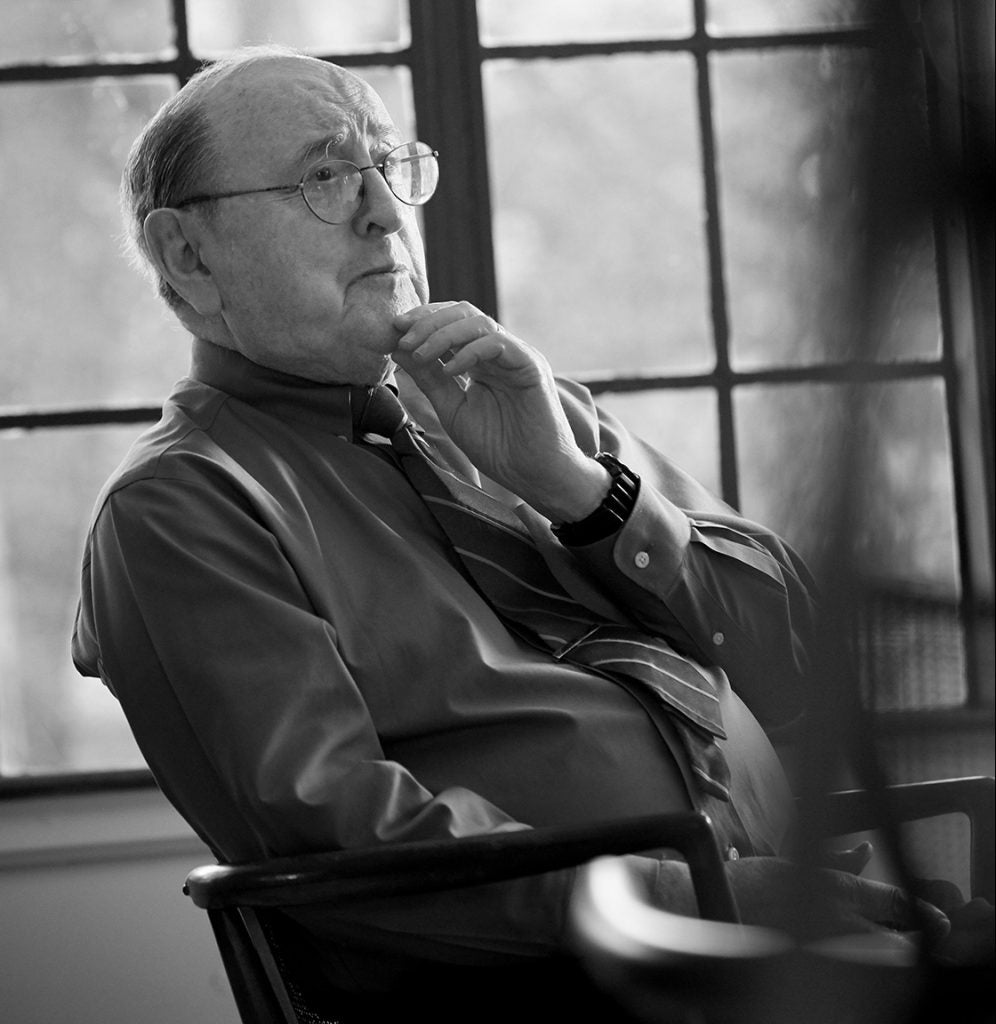

Bernard Lown inspires scholars from developing countries to tackle the root causes of cardiovascular disease

Bernard Lown inspires scholars from developing countries to tackle the root causes of cardiovascular disease

On a December day in 1985, a Russian journalist collapsed from a heart attack during a press conference for two cardiologists poised to accept the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the organization they co-founded, the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW). Without hesitating, Bernard Lown, now professor emeritus at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and his Russian colleague Evgeny Chazov—doctor to Soviet leader Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev—rushed to help the man when he fell out of his chair. Chazov and other IPPNW doctors resuscitated the journalist from what seemed like certain death, and he miraculously survived.

Lown later told those present at the press conference that they had witnessed what it means to be a doctor. “We do not delay treatment to learn the politics or character of the victim,” he said. “The only thing that matters is saving a human life.” And as doctors, he added, they also had no moral choice but to act to prevent the catastrophic threat of nuclear war.

“After the preventable death of a young boy who had to travel to the hospital in a makeshift ambulance, “I could do one of three things: forget this incident ever happened, remember it as a nightmare, or accept this failing as a challenge tobe fixed,” says Pakistani physician and 2018 Lown Scholar Mohsin Ali Mustafa. “I have chosen the latter and decided to dedicate my life to fixing problems in the health care system around me.”

A sense of moral urgency to remedy the world’s wrongs has been with Lown since he left Lithuania at age 14 with his Jewish family to avoid Nazi persecution. It informed his work as a cardiologist, which has focused on preventing sudden cardiac death, one of the most common causes of death in the United States. He pushed the field of cardiology forward technically—notably by revolutionizing care of patients with heart attack through development of coronary care units, and by developing the direct-current defibrillator and heart-monitored exercise testing—while also exploring the root causes of disease and becoming involved in activism for peace.

Now 97, Lown remains passionately connected to the world and to his work. Although retired for the past decade, he has kept a hand in the School’s Bernard Lown Scholars in Cardiovascular Health, a training program for mid-career public health scientists and professionals from low- and middle-income countries. Cardiovascular disease has been rising around the world, because of diet and exercise trends, urbanization, smoking, and chronic stress. As Lown sees it, health care systems in developing countries lack the trained workforces needed to deal with the crisis. True to form, he has been on the case.

In 2009, he launched the Lown Scholars program, funding it with what remained in his research budget on his retirement. Since then, the program has recruited 51 Lown Scholars from 20 countries across Latin America, Africa, and Asia, including Argentina, Lebanon, and Nigeria. Each year, the newly admitted group of about a dozen Lown Scholars comes to Boston to attend a four-week summer program. During the program, scholars team up with faculty mentors to craft proposals for cardiovascular disease prevention projects. Current projects include working with women’s self-help groups in the slums of Kerala, India, to lower hypertension rates, and interventions to improve diet and lifestyle among factory workers in eastern Nepal.

Through the program, Lown hopes to remedy some of the “brain drain” of health professionals and researchers from these countries. That’s why he made having a full-time position in a developing country an acceptance requirement. He wants scholars who are already committed to careers in their countries and will take back what they’ve learned from their Harvard mentors.

A multiplying effect

In the past two years, the program included a course led by Harvard Chan School faculty on global cardiovascular disease prevention and weekly seminars on topics such as nutrition and research methods. A highlight was the visit to a neighborhood health center in Central Falls, Rhode Island—a low-tech facet of the U.S. health system that many in the program didn’t know existed.

“The Lown Scholars strive to improve cardiovascular health in developing countries through combining two major roles,” explains Goodarz Danaei, associate professor of global health and the faculty director of the program. “As scientists, they are pioneers in developing new knowledge. As public health professionals, they embody the social responsibility aspect of Dr. Lown’s work to design programs in their countries that help those most in need.”

After honing their proposals over the summer, Lown Scholars have the opportunity to apply to the program for seed money. Those who are funded may be invited to return the following year to present the progress of their projects and mentor the next year’s cohort. All receive ongoing mentorship from Harvard faculty and access to the growing worldwide network of Lown Scholars.

Vilma Irazola returned this year to report on her project—an assessment of the ways that the built environment affects the diet and physical activity of adults in four communities in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Irazola, the director of the Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy in Buenos Aires and co-director of the South American Center of Excellence for Cardiovascular Health, has been working with Harvard Chan School Professor of Demography Marcia Castro.

“Everyone on my team—and the teams we work with—is benefiting from Marcia’s mentorship and expertise,” Irazola says. “The Lown Scholars program has a multiplying effect.”

Reviving community health centers in low-income countries

This year, the program is working for the first time with several of the scholars to develop plans to establish primary health care centers as a social enterprise in Africa. The program is also partnering with two institutions in South Asia to expand their existing primary health care centers. The centers will be located in areas where access to primary care is limited. Lown hopes that through their close ties to their communities, scholars will gain valuable insights into the most effective types of interventions for improving the local population’s cardiovascular health.

Physician Mohsin Ali Mustafa, who was admitted to the program this year, is developing a plan to expand the clinic he established in Karachi, Pakistan, into a network of 10 clinics. Known as Clinic-5, it currently partners with nearby schools, which pay the equivalent of one dollar per child per month in exchange for in-school first aid, health education, and free medical care at the clinic for students and their parents. Mustafa is now scaling up services from two schools to eight.

The idea for the clinic was born during his final year of medical school, when Mustafa was volunteering in a local emergency room. There, he failed to save a young boy who had been forced to travel to the hospital for 12 hours in a makeshift ambulance, because no nearby facilities could treat his respiratory distress.

“I could do one of three things: forget this incident ever happened, remember it as a nightmare, or accept this failing as a challenge to be fixed,” Mustafa told a writer at Aga Khan University, where he earned his medical degree. “I have chosen the latter and decided to dedicate my life to fixing problems in the health care system around me.”

It’s an ambition he later shared with Lown. They agreed that doctors must take on a larger role in society beyond the examining room, Mustafa says. “Dr. Lown strongly emphasized that if you identify a problem somewhere, it is your responsibility to fix it.”

One-on-one with Dr. Lown

Every program scholar has a one-on-one meeting with Lown in his home, and many find it to be a memorable conversation. Lown likewise calls it a highlight of his year, though he adds that he actually does very little talking. “I don’t have an agenda,” he says. “I listen.”

Lown has little interest in touting his own legacy, although he will show an interested visitor a table of “trinkets” including the Nobel Prize, and his wall of photos. “This is my first meeting with Gorbachev,” he says, with the casualness of a man sharing a family travel snapshot. He will, however, allow that he hopes he has served as a good role model for taking a stand on one of humankind’s biggest perils, nuclear war.

Lown also hopes that if Lown Scholars take home nothing else, they learn the art of paying attention to the complexity of people’s lives. Health is not just about cholesterol and blood pressure, he says. It’s about cramped living conditions, garbage in the street, and all of the stresses people experience in their daily lives. “People aren’t used to being listened to,” he says. “Sometimes a listening ear is all it takes to give individual patients—but also concerned citizens anywhere—the power to envision change and to act.”

– Amy Roeder is associate editor of Harvard Public Health.

Photos: Kent Dayton/Harvard Chan School, Nilagia McCoy/Harvard Chan School