Front Page

For many immigrants, U.S. health care is a maze without a map

What America’s most diverse square mile teaches us about health care access

How to reverse the decline in U.S. maternal health

Moms need help navigating a bewildering system of specialists.

Public health reformers need better communication tools

Strategic communication helps turn untested ideas into forces for real change.

Why every campus should have a student director of public health

University policies often don’t reflect what students actually need.

Snapshots

Bite-sized views of big ideas in public health

Environmental Health

A farewell to HPH readers

The last story for a magazine that looked at what worked in public health, what didn’t, and why.

The new kind of volunteer firefighter

How a brigade of locals became a key force in helping protect people from the L.A. wildfires

Hope as a catalyst for change in Climate Futures

How public health can move from doomscrolling to action

Equity

A farewell to HPH readers

The last story for a magazine that looked at what worked in public health, what didn’t, and why.

Why Black patients are less likely to get life-saving kidney transplants

Innate bias, residential segregation, and the high cost of donation are all barriers.

The neurological impact of being Black in the U.S.

A new theory about how racism may lead to faster aging

Global Health

Can traditional medicine help solve Kenya’s diabetes crisis?

The science says yes. Now Kenyan policymakers can provide a model for other low-income countries.

To meet demand, blood donation should not rely solely on volunteers

A misalignment between supply and demand especially hurts people in low-income nations.

What’s working in the 19 countries on track to help end AIDS

Lessons from Botswana, Cambodia, Zambia, and Malawi

Mental Health

A farewell to HPH readers

The last story for a magazine that looked at what worked in public health, what didn’t, and why.

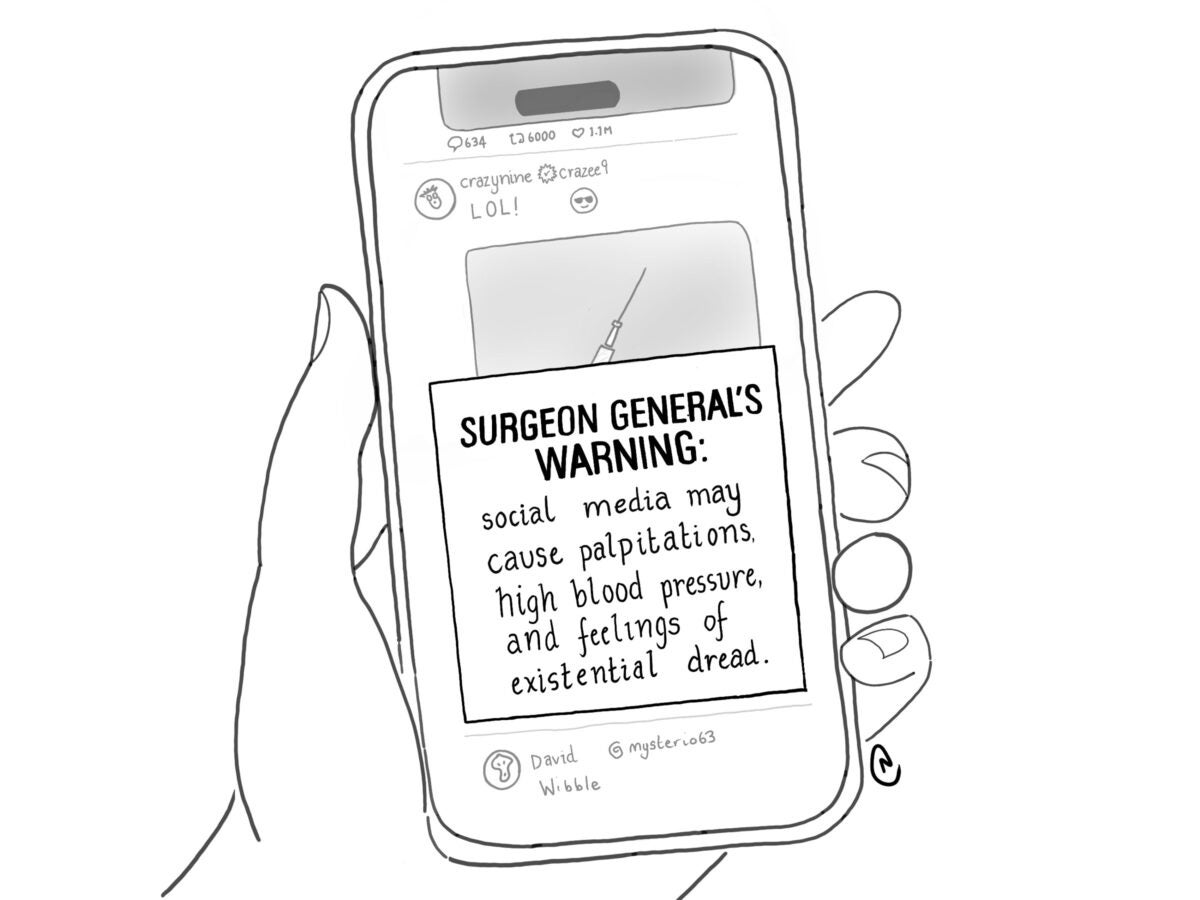

Death by a thousand “likes”

An editorial cartoon by Natasha Loder

Migrant children struggle to express themselves in words. Enter art and play.

Research shows art and play therapy can help children process complex trauma.

Policy & Practice

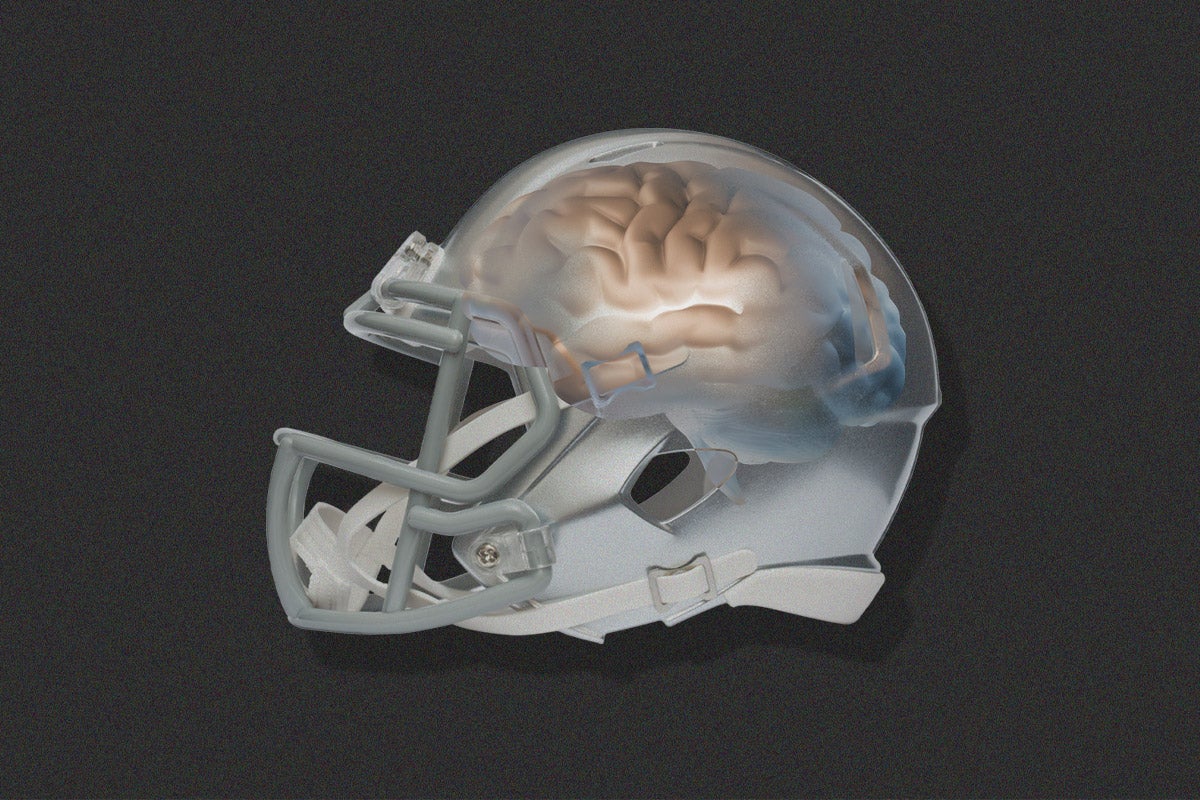

There’s a way to deal with brain injuries in football. It isn’t safety gear.

The NFL says new equipment works, but science disagrees.

“When you design roads, that is public health.”

Research shows people in the U.S. think traffic deaths are inevitable, but they’re aren’t.

Way Home invites the U.S. to view its homelessness crisis up close

A picture of the unrelenting displacement, danger, and exclusion experienced by the unhoused

Reproductive Health

Battling period poverty in Kenya

“This is what you can do with this position, as a woman in power.”

Hispanic women are less likely to get PrEP treatment. A new intervention could change that.

Latinas make up 17 percent of U.S. women, but 21 percent of those living with HIV.

Adopt-A-Mom wants to eliminate pregnancy disparities in North Carolina

The program responds to racial and insurance-based inequities in maternal care in Guilford County.

Tech & Innovation

A farewell to HPH readers

The last story for a magazine that looked at what worked in public health, what didn’t, and why.

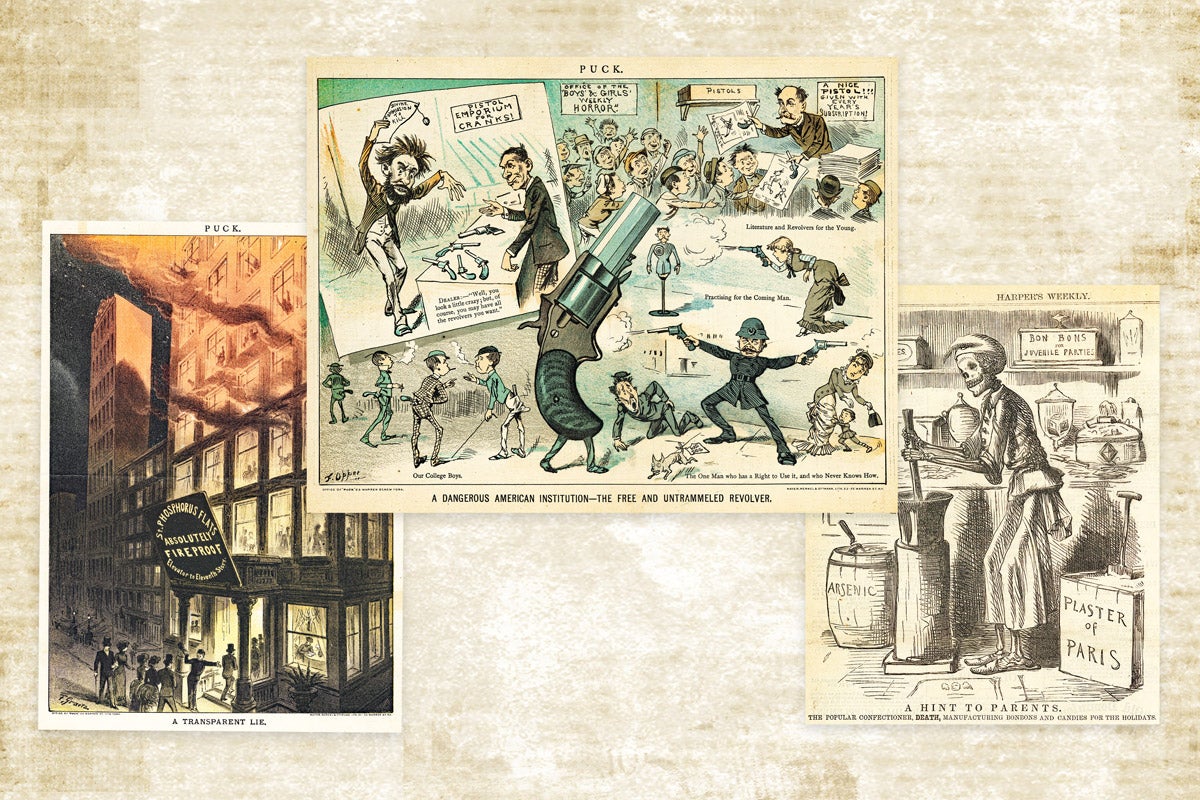

Editorial cartoonists were early U.S. public health advocates

Using caricature and humor to stoke outrage in readers—and change

Social media is the new public health frontline. Let’s treat it that way.

We must give influencers tools and training to deliver accurate health information.