Are electronic cigarettes one of the biggest health hazards since tobacco—or the best chance to get smokers to quit? Without the research needed to answer that question conclusively, public health officials and regulators are in a fix.

At a gas station just across the river from Harvard Square, a bright yellow billboard trumpets “E-Cig and Vaping Specialists.” Advertisements for all of the major e-cigarette brands are plastered on the walls of the station and even the gas pumps. Prominently displayed inside behind the counter, e-cig brands Blu and Njoy—in regular, menthol, cherry, and vanilla flavors—push the Marlboros and Newports to the side.

A mile down the street, Eastern Vapor occupies a second-floor space in a brick office building in the college-kid section of Allston-Brighton. There, the young clerks will gladly show off a $50 starter kit that, with its gleaming, precision- milled metal cylinders, looks as if it was plucked straight from one of Harvard’s nearby science labs. Behind the counter, cartridges of liquid nicotine neatly line the shelves, along with a chalkboard menu that advertises designer flavors, from Tropical Toucan (guava and citrus) to Gorilla Guts (butterscotch and banana).

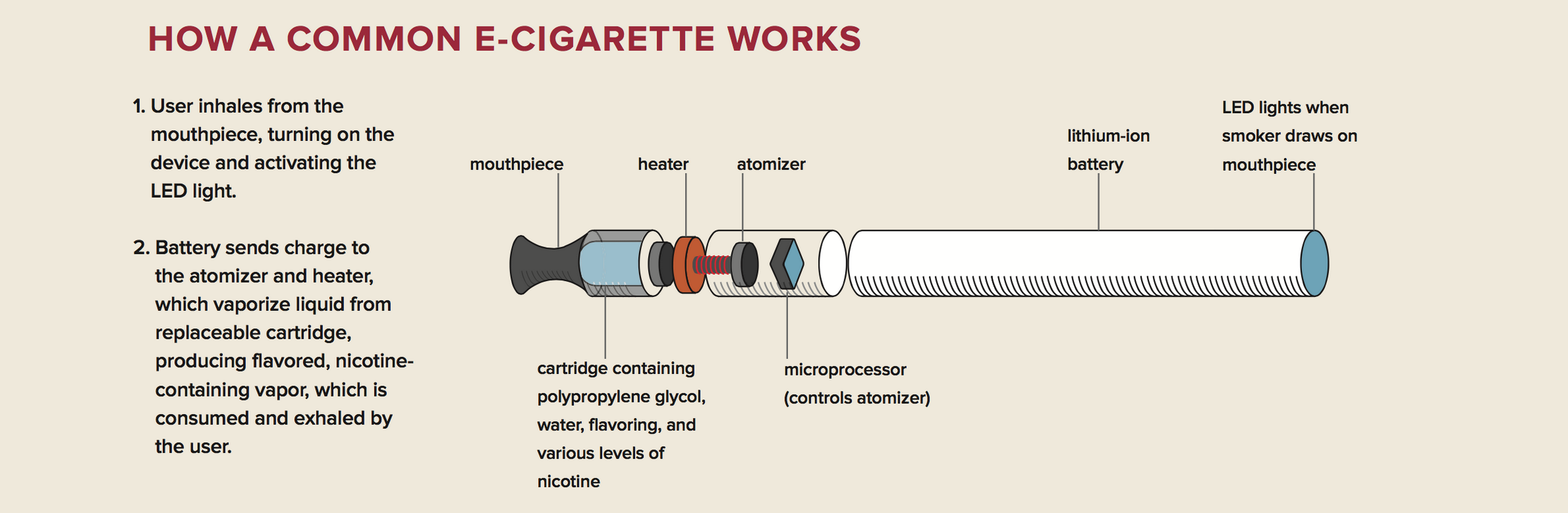

It was only eight years ago that electronic cigarettes—battery-powered devices that heat up a liquid nicotine solution into an inhalable vapor—hit the United States market. Today, annual global sales total upwards of $2 billion (though reliable sales figures are hard to come by, in part because online sales are not recorded in retail surveys). E-cigarettes command a devoted following among ex-smokers, who rely on them to get their nicotine fix while avoiding the harmful side effects of tobacco smoke. Online message boards are full of testimonials by hardcore smokers who have sucked on Marlboros or Camels for decades, only to finally quit with the help of e-cigs. “Vaper” conventions draw converts from around the country to compare the newest nicotine delivery systems and compete to see who can blow the biggest cloud of steam. And e-cigarettes have gone mainstream, starring in Super Bowl ads and dangling from the lips of celebrities, from Katherine Heigl to Leonardo DiCaprio.

At the same time, teens and young adults—many of whom have never taken a drag on a combustible cigarette—are “vaping” just for kicks. Youth are a key target market for e-cig companies, which lean heavily on social media advertising. One company, Blu eCigs, has created an e-cig with a carrying case that glows blue with another vaper using the same brand is nearby.

Side by side, these trends present a big dilemma for public health.

Doubt is a powerful product.

For decades, tobacco companies did everything they could to convince smokers that cigarettes weren’t killing them—insisting the jury was still out on the science despite dozens of studies that linked smoking with lung disease and cancer. As one tobacco executive famously wrote in 1969, “Doubt is our product…the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the minds of the general public.”

In the case of e-cigarettes, however, the jury really is still out, with scant scientific studies about whether they are a salvation for hard-core smokers, a potential scourge for young novelty seekers—or something in between.

Surgeon General Vivek Murthy says health officials are “in desperate need of clarity” to help guide policies on electronic cigarettes.

Which is why, for public health, the sudden explosion of e-cigarettes into mainstream culture has created a quandary. On the one hand, they represent a potential game changer for smoking-cessation efforts—giving new hope to long-time puffers who have tried unsuccessfully for years to quit. On the other, they introduce an untested, potentially dangerous product that could not only spawn a whole new generation of nicotine addicts, but also serve as a gateway to regular cigarettes—just as U.S. smoking rates have hit an all-time low.

A Scientific Haze

In February 2015, the new U.S. Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, said health officials are “in desperate need of clarity” on electronic cigarettes to help guide policies.

We know what substances in cigarettes do the most harm. According to the American Cancer Society, the smoke produced by burning dried tobacco leaves and other additives contains a complex mixture of more than 7,000 chemicals, including more than 70 known to cause cancer and, in some cases, heart and lung disease. Among these deadly substances are cyanide, benzene, formaldehyde, methanol, tar, and poisonous gases such as carbon monoxide. Smoking accounts for at least 30 percent of all cancer deaths in the United States.

We know less about exactly how dangerous nicotine—the addictive and psychoactive substance in cigarettes and e-cigs—is. Surprisingly, few large-scale studies have examined nicotine addiction separate from cigarette smoking. Some studies on nicotine replacement therapy (such as patches and gum) during pregnancy have found adverse effects on fetal development and an increase in preterm labor, though at rates lower than those linked to cigarettes.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nicotine, which stimulates the plea- sure and reward pathways in the brain, is as addictive as heroin, cocaine, and alcohol. It causes blood vessels to constrict, raises blood pressure, and can trigger abnormal heart rhythms. One of the biggest questions in the current e-cig debate is whether nicotine harms neurological devel- opment during adolescence, a critical period for brain growth. And according to a CDC study, the number of calls to poison centers nationwide involving e-cigarette liquids containing nicotine rose from one per month in September 2010 to 215 per month in February 2014.

Is E-Cig Vapor Benign?

While e-cigarette vapor has far fewer hazardous components than cigarette smoke, it is not benign, according to a small but growing body of scientific literature. A January 2015 health advisory from the California Department of Public Health noted that, “Chemicals in the aerosol are absorbed through the bloodstream and delivered directly to the brain and all body organs.” It added that, “E-cigarette emissions also contain volatile organic compounds and fine/ultrafine particles. These ultrafine particles can travel deep into the lungs, where they get trapped and may lead to tissue inflammation.” Among the ingredients in e-liquids, the advisory said, are “flavoring agents, propylene glycol, and toxic chemicals known to cause cancer, birth defects, and other reproductive harm.”

According to a 2014 review published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), e-cigarettes contain varying levels not only of nicotine, but also of potentially harmful nitrosamines, aldehydes, metals, volatile organic compounds, phenolic compounds, and other substances. “Various chemical substances and ultrafine particles known to be toxic, carcinogenic and/or to cause respiratory and heart distress have been identified in e-cigarette aerosols, cartridges, refill liquids and environmental emissions,” the researchers noted. Other studies have found that e-cigarettes produce high levels of nanoparticles, which can trigger inflammation and have been linked to asthma, stroke, and heart disease.

This past January, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine found that exposure to the carcinogen formaldehyde—produced when the propylene glycol and glycerol in e-cig solutions are heated, sometimes at upward of 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit—could reach levels five to 15 times higher than formaldehyde levels in cigarette smoke. In February, a study published in PLOS One found that mice exposed to e-cig vapor suffered impaired immune defenses against bacteria and viruses in the lungs, and that the animals were more susceptible to influenza. The immune-system effects of e-cigarette exposure, the authors concluded, “are similar to those observed after exposure to cigarette smoke.”

Other studies have found that the nicotine in e-cig vapor penetrates the bodies of bystanders at levels comparable to those of people exposed to secondhand cigarette smoke. And propylene glycol, one of the main base ingredients in e-liquid, is known to cause eye and respiratory irritation.

Yet scientists don’t know how this worrisome laundry list of potential problems plays out across populations over years or decades of use. “E-cigarette products are so new, the long-term effects are unclear,” says Kasisomayajula “Vish” Viswanath, professor of health communication at the Harvard Chan School, who has been involved in crafting a policy statement on e-cigs for the American Association for Cancer Research, released jointly with the American Society for Clinical Oncology. “For example, we don’t know what happens when people ingest nicotine combined with propylene glycol,” which carries both the nicotine and the flavor solutions.

“They are by design definitely less dangerous than cigarettes, but they are not a healthy alternative to smoking—quitting is the healthiest alternative,” notes Constantine Vardavas, a former research scientist in the School’s Center for Global Tobacco Control, now at the University of Crete. He was lead author of a 2012 study in the journal Chest that found that inhaling e-cig vapor damages lung function—though the long-term or clinical health impact is unclear.

So what kind of research would clear the air? Public health investigators would like to see studies that clarify how and under what circumstances people are using e-cigarettes; long-term studies of health effects; clinical trials that show how effective e-cigarettes are compared with conventional cessation approaches in helping people quit smoking; and targeted laboratory studies that analyze the harmful constituents of e-cigarettes.

Public Health Rifts

With so much not known, the ambiguity about health risks and health benefits has created a rift within the tobacco- control community. “There has been a genuine and perceptible disagreement among people who are very committed to tobacco-control research,” says Viswanath. “You cannot question anyone’s motives here.”

Conflicts within public health aren’t new, of course—consider the lingering controversies over saturated fat or mammograms. But it is surprising to see this dispute play out in a community where previously the only disagreement about cigarettes had been over which regulations were needed and how quickly. “It has split tobacco researchers into two groups: those for and against,” notes Vardavas. “It’s horrific to watch—it’s almost like a civil war.”

Viswanath agrees, adding: “There are clearly two sides, or three sides if you include those like me in the middle trying to figure out what the heck we are talking about.”

Yet other Harvard Chan researchers sense that over the past year, the public health community may be moving toward a tentative agreement on the potential benefits of e-cigarettes. According to Vaughan Rees, interim director of the School’s Center for Global Tobacco Control and an expert on substance abuse and dependence, the field is coalescing around the idea that, if regulated properly, e-cigs could bolster overall harm reduction by helping smokers quit tobacco cigarettes or helping them smoke less. The trick will be regulation, he adds. “Harm reduction can only work in a regulatory environment that encourages complete switching among current smokers or tobacco users, and discourages use among adolescents.”

Rees’ suggestion for achieving this net harm reduction may sound counterintuitive and even risky: Make e-cigs more addictive, by raising their nicotine levels. His rationale is that low-nicotine e-cigs are both less likely to deliver the kick that will enable smokers to completely switch and, because of their mild flavor, are more likely to hook young people on nicotine. “We’re eager to find the sweet spot,” says Rees, “where we support switching away from tobacco cigarettes without unintentionally increasing an individual’s nicotine dependence.”

Regulating E-Cigarettes Will Take Time

How shall officials regulate e-cigarettes? “The key issue is: What is the public health cost of a nicotine addict compared to that of a smoking addict?” says John Quelch, professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard Chan School and the Charles Edward Wilson Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

“Obviously, the goal is to get e-cigarettes regulated as quickly as possible, so we can advance the possible benefits of e-cigarettes while minimizing any harm,” says Howard Koh, professor of the practice of public health leadership at the Harvard Chan School and former U.S. assistant secretary of health.

But Koh adds that federal rulemaking is highly delib- erative and notoriously time consuming. “There is going to be a period of uncertainty until all of the regulatory policies are put in place,” he says.

Feds Need Data to Act

Without being able to cite robust studies, the FDA and the European Union’s Tobacco Control Directive have been caught flat-footed, unsure of how to regulate e-cigarette use. A 2014 FDA proposal recommended restricting sales to minors, mandating disclosure of ingredients, and requiring warning labels that state nicotine is an addic- tive substance. But these measures fall short of curtailing advertising, banning flavors, or reducing vaping in public. According to Vaughan Rees, with e-cigarettes quickly evolving to deliver more nicotine, there is a desperate need for regulations that both require product standards about nicotine content (so that smokers get enough nicotine to quit) and eliminate exposure to potentially toxic chemicals.

One hurdle is that the FDA is required by law to base regulations on scientific studies—with the possibility of legal challenges by e-cigarette companies if regulators overreach. “The emphasis on data is very strong,” says Koh. “With attempts at regulation there is always the threat of litigation, so the FDA is moving with all deliberate speed to make sure the decisions they are making will withstand scrutiny.”

The agency has called for long-term prospective studies on the effects of e-cigarettes, supported by a call for proposals by the National Institutes of Health to support such research. But given the slow pace of regulatory action, it may be one or two years before the research is launched, and at least three years before public health conclusions can be drawn from the first longitudinal studies. That lag may give the new products more than enough time to establish a foothold in the market.

That’s too long, e-cigarette opponents say. The government already has enough evidence to move on e-cigs and should err on the side of caution, they claim, in case the hot new products turn out to be a health menace. “E-cigarettes are a double-edged sword,” notes Koh. “While they could potentially advance smoking cessation, currently they are a disruptive product of unknown safety and efficacy.”

Critics are convinced that e-cigarette companies prefer to do business in what has often been characterized as a “regulatory Wild West.” “They’re operating in a completely unregulated environment right now, and it’s enabled the e-cigarette industry to go from virtually zero to billions of dollars a year over the past five or six years,” says Rees. “Who wouldn’t want to operate in a completely unregulated environment where profit is concerned?”

State and Local Regulations Quicker

In the absence of federal action, states and localities—which are empowered by law to move more quickly to regulate public smoking—have begun clamping down. Today, four states—Arkansas, New Jersey, North Dakota, and Utah, as well as the District of Columbia—have placed e-cigarettes under the purview of existing laws that prohibit smoking in public, and more states have passed narrower laws forbidding vaping in schools and other specific locales. And nearly 300 cities and counties—including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco—have banned e-cigs in restaurants, bars, work- places, and casinos.

Both Harvard University and the Harvard Longwood Campus include e-cigarettes in their smoke-free policies.

Distracting from the Tobacco Threat

Constantine Vardavas worries that evolving trends in public smoking could lead to a new acceptance of both electronic and tobacco cigarettes, particularly among dual users. “We’ve spent millions of research dollars and all the tobacco-control efforts of the past decades to denormalize smoking in public places, and a nod of approval to e-cigarettes passes along a message to youth that it’s OK,” he says. “Whatever smoking rules exist for conventional cigarettes should exist for e-cigarettes, so you are reducing smoking and not renormalizing it.”

That renormalization applies to marketing as well. Conventional cigarette advertising is prohibited on television and radio, on billboards and public transportation, and in magazines targeted to youth—but no such bans apply to e-cigarettes, which seem specifically targeted to teens. “When you see a magazine ad with a sexy girl in a bikini with the slogan, ‘Slim. Charged. Ready to Go.’—that is not aimed at a 55-year-old who is quitting smoking,” notes Vardavas. “That is made to appeal to adolescents.”

While it’s important to get e-cigarette regulation right, Vardavas adds, it’s not worth advocates’ fighting among themselves only to lose sight of the continued threat of tobacco smoking, especially in countries outside the United States. “If we focus too much on the trees of the e-cigarettes, we risk missing the forest of conventional tobacco use. That risk is still magnitudes more important, and is still going to be a major public health issue around the globe.”

“There is tremendous concern we could reverse our success in denormalizing the addiction of cigarettes,” says Koh. “We could introduce another potentially addictive agent to young people and undermine the progress we’ve made on tobacco control in general.”

If there is a silver lining in the vaping cloud, it may be that the debate on e-cigarettes has pointed the spotlight on the harmful effects of all cigarettes. “Too often the public thinks that the tobacco problem has been solved,” says Koh, “but in the U.S., we still have over 1,000 people dying a day from tobacco addiction. E-cigarettes use can be a means to bring urgent new attention to the ongoing complexity of this tremendous addiction.”

And despite the potential dangers that increased e-cigarette use poses, the public health community is better positioned to deal with the issue than it was decades ago, when tobacco companies intentionally obscured the dangers of conventional cigarettes. Decades passed between the 1964 surgeon general’s report on smoking and health and strong government policies regulating cigarettes, such as higher taxes on the product, laws against smoking in public places, and health warning labels. “The tobacco-control community is much better organized than we used to be,” says Viswanath. “We now know that conventional cigarettes produce very harmful effects over time. We learned our lesson.”

E-cigarette ads, including those that appear in social media platforms, clearly target a youth audience.

Images courtesy of the collection of Stanford University

Teens Perceive Scant Risk in E-Cigarettes

Trends in youth e-cig use are especially worrisome, since they presage behaviors that may be difficult to alter once young e-cig consumers become adults. Are teenagers experimenting with e-cigs on the way to becoming smokers, as a way to transition away from smoking, or both at once—for example, smoking while at home and vaping at the bar? Researchers won’t know for sure until they are able to conduct longitudinal studies that follow the same subjects over years to determine their patterns of use.

“We need to follow a group of adolescents over the next few years to figure out who has experimented with e-cigarettes and why,” says Constantine Vardavas, a former research scientist at the School’s Center for Global Tobacco Control. The implications of such studies will be crucial in settling the debate about whether e-cigs should be tightly regulated as a dangerous hazard or embraced as a therapy for smoking cessation.

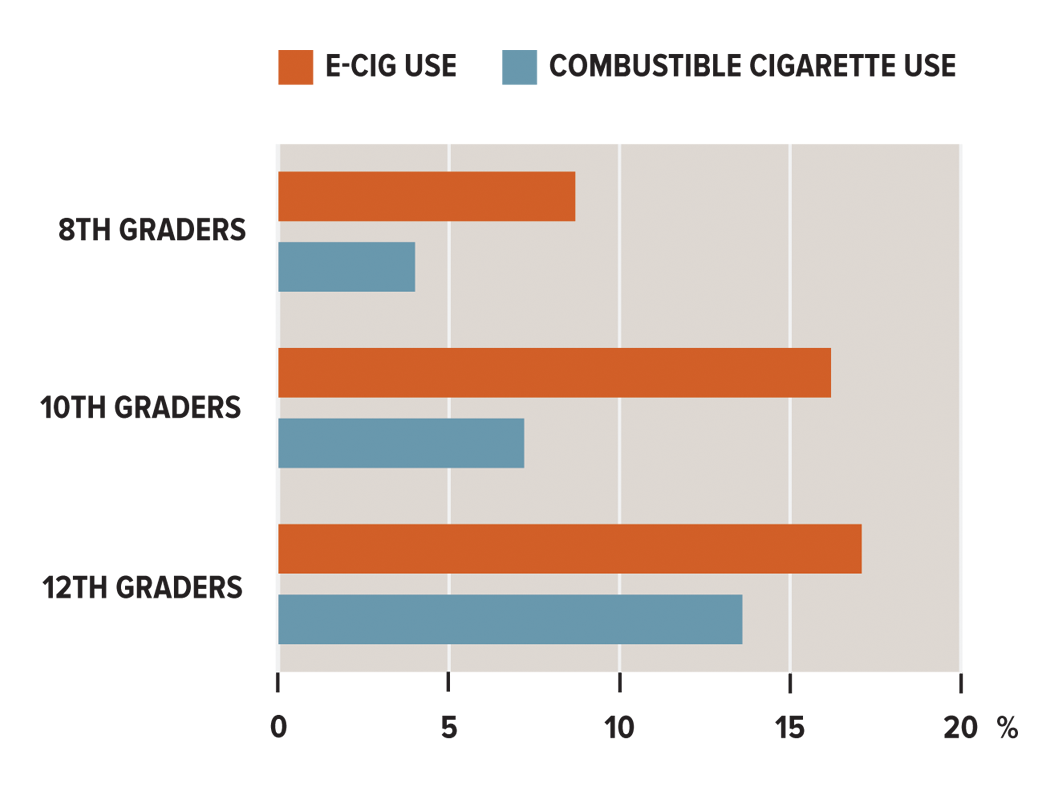

E-cigarettes outpace combustible cigarettes among teens.

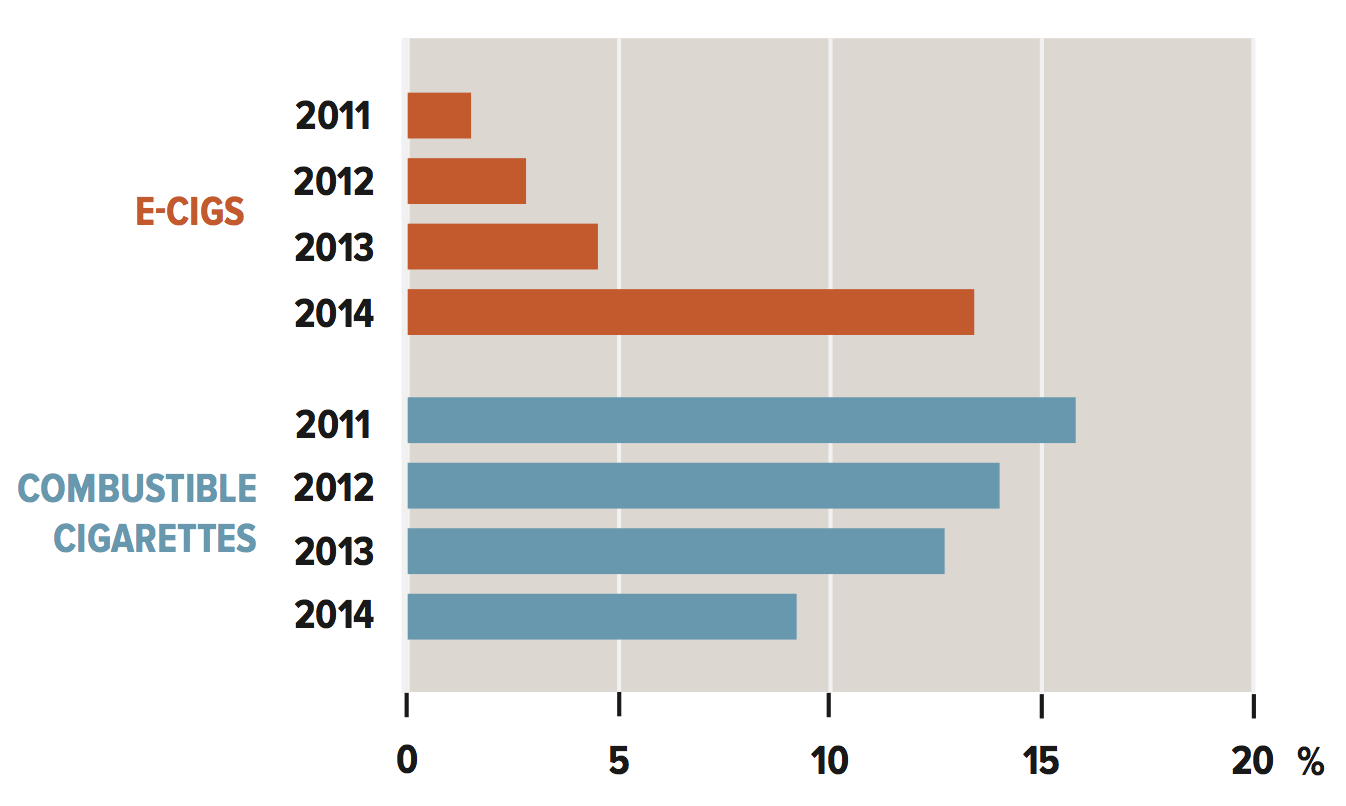

E-cig use is skyrocketing among high school students.

While teen e-cigarette use has soared over the past few years, teen smoking has plummeted to 9.2 percent—the first time that teen smoking rates in the U.S. have ever hit single digits. Many researchers believe that e-cigarettes may be diverting teens away from combustible cigarettes.

Source for both charts: Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E. & Miech, R. A. (2014). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Vaping: One Man's Experience

The first time Ted Read saw an electronic cigarette, four or five years ago, he was volunteering at a film festival. His boss, whom he describes as “sort of a hipster,” pulled out a cigarette that looked just like a tobacco cigarette—only no smoke came out when she puffed on it. “She whipped out one of these ‘cigalikes’ and was kind of smugly smoking it indoors,” he recalls.

The first time Ted Read saw an electronic cigarette, four or five years ago, he was volunteering at a film festival. His boss, whom he describes as “sort of a hipster,” pulled out a cigarette that looked just like a tobacco cigarette—only no smoke came out when she puffed on it. “She whipped out one of these ‘cigalikes’ and was kind of smugly smoking it indoors,” he recalls.

Read, a smoker, wasn’t impressed.

Fast-forward to February 2014. Read had flown from Boston to Portland, Oregon, for a wedding and knew that during a long layover he wouldn’t be able to light up. He picked up a pack of Blu electronic cigarettes—known for the blue LED at the tip that illuminates when a person takes a drag. “In Portland, I was in a rental car driving through a strange city. I needed to smoke,” he explains, sitting in a park near Harvard Square, looking like something of a hipster himself in a fedora, plaid shirt, and Converse sneakers. “But my wife doesn’t let me smoke in the car. So I tried this e-cigarette.” For the rest of the trip, he thought about buying tobacco for the pipe he usually smoked. “But I didn’t,” he says, with some wonderment. “I kept sucking on the e-cigarette with that blue light.”

Read had been a smoker for more than 30 years, starting at boarding school at 14 and continuing through last year as a “beard-stroking pipe smoker” at 46, despite the fact that his wife, a communications professional at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, deplored the habit and asked him to quit every few months. An electronic musician, Read had tried repeatedly to quit, but inevitably some new source of stress would send him back to smoking. “Something would happen,” he says, “and I’d find myself almost subconsciously at the convenience store.”

After the Portland trip, he began researching e-cigarettes, going online to order a thin metal tube known as a “clearomizer.” He pulls it apart to show the hole where he pours in a solution of nicotine and chemicals, mostly propylene glycol (PG)—available in a range of flavors (Read prefers the fruity ones). The other half of the tube holds a battery. When a small button is pressed, it activates a heating coil inside that vaporizes the solution, which Read inhales and then breathes out as clear vapor.

Today, Read has quit smoking a pipe and only occasionally smokes a cigarette, when hanging out with friends in the music scene. And he’s gone from “vaping” a solution of 24 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter of PG to one of 6 mg/mL, and hopes to get that down to 3. “I was breathing better almost immediately,” he says. “My teeth are whiter, and I don’t always smell like smoke.” The biggest benefit, however, has to do with his wife. “She is always looking at me and smiling.”