A 20-year partnership among the Boston Housing Authority, public housing residents, and academic researchers eases some of the health hazards born of poverty.

Every few months, Willie Mae Bennett-Fripp and her neighbors went to war with the roaches. It was the 1970s, and Bennett-Fripp, a young African-American woman, was living in a hulking, brick-and-concrete three-story walk-up in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. The public housing development was called Orchard Park—after the trees that once grew there—and its residents had learned the hard way that spraying one apartment at a time simply sent the hardiest roaches scurrying to other units.

“We’d pick a Saturday when everybody could go away for the day, and before we left, we’d set off roach bombs to fog everybody’s units and the hallways,” recalls Bennett-Fripp, 62, who now leads the Committee for Boston Public Housing, a tenants-rights group.

The simultaneous attacks beat back the pests, for a while. Soon enough, though, the insects would return—swarming under cabinets and stoves, climbing onto the ceilings and dropping onto dinner plates—until the residents could coordinate another assault. For years, similar battles raged across Boston’s public housing developments. Every so often, a thick pesticide fog would hit an open flame, such as a stove’s pilot light, triggering explosions that blew out windows.

Public housing residents knew they were losing this war, and others as well. They also faced rodents, dust mites, and mold spreading from leaky pipes. Secondhand cigarette smoke seeped through cracked walls. Apartments were overheated or unheated. Fumes from stoves used for heating wafted in the stagnant air with little ventilation.

Boston Housing Authority (BHA) leaders were also deeply troubled

by the problems. “We couldn’t be the typical landlord. We needed to partner with residents to correct these problems,” says Sandra Henriquez, who led the BHA from 1996 to 2009. “I didn’t want us to be the enemy, because we weren’t.”

So it was no surprise to either the residents or the BHA when, in the late 1990s, researchers from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston University, and Tufts University contacted them, suggesting links between their housing and chronic illnesses—notably asthma, which was an epidemic among the nation’s urban poor. The ambitious research partnership that followed was ground-breaking—in every sense of the word—and became a national model for cooperation between scientists and housing authorities.

At first, though, the researchers needed to overcome deep skepticism among those most directly affected by the effort. “The residents said, ‘They ain’t going to prove nothing that we don’t already know,’” recalls Bennett-Fripp. “‘We live this every day. We already know: Raggedy houses make people sick.’”

Leap of Faith

But actually proving—with objective data—what people already knew took more than a decade. It meant men and women from very different worlds had to overcome stereotypes and mutual suspicions as they worked toward a common objective of healthier housing.

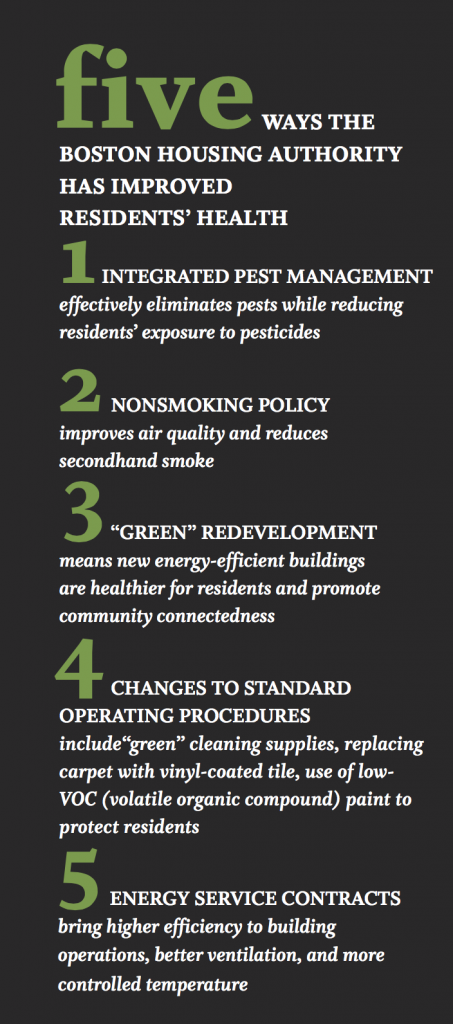

The alliance of residents, researchers, and housing managers became known as the Healthy Public Housing Initiative, and it has racked up an impressive string of achievements. First, the collaborators found a way to fight roaches more effectively and with less toxicity. Then they banned smoking. Finally, they transformed entire developments into “green housing” that’s both energy-efficient and healthier. As a result, asthma rates in Boston public housing plummeted.

“People often talk about health disparities in the abstract,” says Gary Adamkiewicz, MPH ’02, assistant professor of environmental health and exposure disparities at the Harvard Chan School and a longtime leader in public housing research. “But I can walk into somebody’s house and see peeling lead paint, or mold clinging to the walls. Or maybe it’s a neighborhood without green space, next to a highway choked with rush-hour traffic, or down-wind from a refinery with the pollution blowing into open windows. These problems are not at all abstract. And many can be fixed.”

Asthma Alarms

In the mid-1990s, Boston pediatricians grew frustrated by how often poor kids with asthma showed up in the emergency room gasping for air, despite having the medications and inhalers that usually kept severe attacks at bay.

Nationwide, asthma rates jumped 75 percent between 1980 and 1994, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and they have remained elevated ever since. The biggest increases were among children, poor people, and minorities. At the same time, a growing pile of studies linked asthma with allergens such as mold, dust mites, and cockroaches. In the case of roaches, the bugs’ saliva, feces, and shedding skin are all allergy triggers.

Boston Medical Center doctors came to the depressing suspicion that young patients might be allergic to their own homes. At BHA developments— which today shelter about 25,000 Bostonians, nearly three-quarters of whom are Latino or African-American, with an average household income of about $14,000—asthma rates were more than twice the citywide average.

The hospital hired a lawyer versed in city housing code to join its pediatric department and cosign letters with doctors telling patients’ landlords to clean up their properties. Megan Sandel, now medical director of the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, was among the pediatricians who joined the effort.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, she wrote countless letters to the BHA, demanding that families be moved into apartments that wouldn’t make children cough, wheeze, miss school, and end up in intensive care.

“I’d write doctor’s orders for a pest-free home,” Sandel recalls. The response from many BHA property managers was, in essence, “We don’t have any of those.”

Toxic Homes

Henriquez concedes that Boston’s public housing stock was toxic for residents. The BHA oversees more than 60 developments, many built in the 1930s and ’40s. By the late 1970s, the buildings suffered from years of deferred maintenance. The surrounding neighborhoods had crumbled too, eroded by rising drug abuse, homelessness, and crime.

When Henriquez started, the BHA was just a few years removed from a decade of court-appointed receivership, imposed after tenants sued over housing conditions. Back then, the turnaround on routine maintenance calls averaged three months (today, it is 24 days). Because of the delays, minor problems often became major disasters.

Henriquez remembers one particular meeting at a housing development early in her tenure, after which she took a walk around the property, alone. When she returned, she looked shaken. An assistant asked if she was OK.

“I said, ‘In Massachusetts, land-lords can be jailed for not keeping up their property,’” she recalls. “‘Based on what I’ve seen here, they should take me to jail for the rest of my life. And when I die, they should come get my children and put them in jail.’”

A Tentative Alliance

In 2000, Jack Spengler, now the Akira Yamaguchi Professor of Environmental Health and Human Habitation at Havard Chan, joined two environmental health professors—Patricia Hynes at Boston University and Doug Brugge, MS ’88, at Tufts—to study asthma and other health issues in public housing. Their work began with health surveys, coupled with home inspections and air samples.

Before getting started, Hynes and Brugge had approached the BHA for its blessing, if not its cooperation. It was a tough sell. The authority was just emerging from the tenant lawsuit, and these studies would likely connect housing conditions with chronic disease, missed work, and hospitalized kids.

“We agonized over it,” Henriquez says. “The fear was that we were going to open ourselves up and give people lots of fodder to go into housing court and rake us over the coals.” But she decided that the BHA had to come to grips with the problem and join the effort to find a solution. As Spengler puts it, “Sandra Henriquez was courageous to open up and allow academics to do research in public housing that might reflect badly on her agency. She understood that public housing need not just provide shelter but could also promote health.”

“We agonized over it,” Henriquez says. “The fear was that we were going to open ourselves up and give people lots of fodder to go into housing court and rake us over the coals.” But she decided that the BHA had to come to grips with the problem and join the effort to find a solution. As Spengler puts it, “Sandra Henriquez was courageous to open up and allow academics to do research in public housing that might reflect badly on her agency. She understood that public housing need not just provide shelter but could also promote health.”

Residents were already mobilizing against asthma when the researchers showed up. Still, the tenants were wary of partnering with academics. According to BU’s Hynes, “Early on, a lot of the public housing residents were suspicious that this was just about getting data for papers that would help researchers gather more funding to get more data someplace else.”

“My perspective,” says Bennett- Fripp, “was that residents had to be at the table, and that everybody was equal. No one was more intelligent or valuable to the project than anyone else.” Although some residents had just a grade-school education, “they were sitting with people who have multiple doctorates,” she points out. “So for the residents to think they’re equal was a lesson to them, and a total shocker for the universities, especially Harvard.”

Spengler admits he was taken aback by the number of tense and often contentious community meetings needed to forge a resident-researcher partnership. “After one of these meetings, I said to Mae, ‘Why do I get the sense that everybody here is mad at me?’” he says. “She said, ‘Jack, you have to realize, when you’re poor, sometimes all you have is your pride.’”

More than Minimum Wage

Equality didn’t just mean mutual respect. It also meant money. The researchers wanted tenants to help interview residents, inspect apartments, and collect air and surface swab samples to be analyzed in the lab. At first, researchers proposed that residents earn $5 for each completed survey. “One researcher said residents should be grateful that we’re trying to come in and save their children’s lives,” Bennett-Fripp remembers.

She rejected that deal, as well as a proposal to pay residents minimum wage. “I said, ‘Is anybody at Harvard getting minimum wage?’” she recalls. “‘Nobody’s going to talk to you unless people in the community get hired and paid decently.’”

The researchers eventually offered $13 an hour for the job of community-health advocate, which later grew to $18 an hour. Residents also made sure survey questions were in plain English (and plain Spanish). Bennett-Fripp and other community partners went on to coauthor the resulting journal articles, and the scientists regularly updated interested residents on research progress.

“The tensions we had are not unique in community research collaborations—it’s just not something people usually talk about,” says Tufts’ Brugge. “But the fact that the work has continued for so long and ultimately been successful, academically and for residents, suggests it was worthwhile to push through the challenges we faced early on.”

A PowerPoint Slide Launches a Career

Growing up in Queens, New York, the youngest child in a working-class family of four, Gary Adamkiewicz stood out for his early love of science.

“I saw firsthand some of the issues I study today,” he says. “But I would never put my experience side by side with what somebody in public housing has gone through.” Still, he says, when you live in a place like New York City, where millionaires and panhandlers share sidewalks, “there’s no way to be blind to the fact that people of different means go home just blocks from each other to very different realities.”

“I saw firsthand some of the issues I study today,” he says. “But I would never put my experience side by side with what somebody in public housing has gone through.” Still, he says, when you live in a place like New York City, where millionaires and panhandlers share sidewalks, “there’s no way to be blind to the fact that people of different means go home just blocks from each other to very different realities.”

After studying chemical engineering as an undergraduate, Adamkiewicz earned a doctorate at MIT with a dissertation that modeled air pollution at the scale of cities.

Almost immediately after graduating, however, he veered in a different direction. Shortly after receiving his master’s from Harvard Chan, he heard about the Healthy Public Housing Initiative, which he joined as research associate in 2003.

The spark launching his new career, Adamkiewicz remembers, was a single, nagging bullet point in the PowerPoint talks he often gave about his doctoral thesis. His first slide, summarizing the motivations for his research, noted the puzzling rise of asthma in cities. “I got tired of confining that fact to my first slide,” he says. “Asthma was at the nexus of environmental justice, social justice, health justice, and really complicated environmental problems. I loved the idea of using science to figure it out.”

Inspired by Silent Spring

The Healthy Public Housing Initiative’s first surveys and home inspections confirmed the links between roaches and asthma. And where there were roaches, there were also lots of cracks in the walls, dampness and mold, clutter, and residue from several pesticides. Clearly, sporadic visits from BHA exterminators and residents’ DIY roach control were ineffective at best and toxic at worst. Roaches needed to be fought systematically—with prevention, not just poison.

Fortunately, there was a model for smarter pest control—first suggested in Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s 1962 pesticide exposé—which had already been widely adopted by farms and the National Park Service. This intricate alternative approach, called integrated pest management (IPM), combined efforts to snuff out the root causes of infestations with frequent monitoring and sparing use of less-toxic pesticides.

The healthy-housing coalition decided to try IPM in Boston’s public housing stock. With foundation and government funding, the coalition launched a small, intensive one-year IPM pilot project. Teams of researchers, BHA maintenance personnel, and resident community-health advocates visited the apartments of 58 asthmatic kids in two developments. They set sticky roach traps for a baseline assessment, advised families on decluttering and securing food and refuse, and spotted maintenance issues, such as wall cracks and water leaks, that could be fixed.

Then they cleaned the apartments with a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) vacuum. Finally, an exterminator killed existing roaches with gel baits and boric acid powders, which had lower toxicity and were more controlled than spray and fog insecticides.

Cockroach numbers and allergen levels dropped dramatically. Before IPM, nearly 80 percent of kids reported wheezing every week, about 70 percent of them said asthma kept them up at night, and a similar number said asthma shut them out of normal activities. After the intervention, asthma prevalence fell by about half. This success would lead to a much larger IPM “demonstration project” in BHA housing starting in 2006. BHA and its partners also created brochures in eight languages, multilingual posters, and a video to teach residents how to identify pests and protect their apartments.

Learning How to Collaborate

Yet even as the public health collaboration strengthened, researchers still had much to learn about the nonscience part of their roles. According to Bennett-Fripp, tenant leaders would sometimes give a “prep talk” to new researchers before they visited a public housing development.

“You didn’t want families to feel embarrassed,” she says. “If you go into somebody’s house and a roach falls on your foot, you just kick it off and keep on talking. If the couch isn’t clean, you sit your butt down.”

Once researchers, housing managers, and tenants started trusting each other, the partnership’s real power emerged. Researchers helped families spot things that might trigger asthma attacks, such as scented candles or plug-in air fresheners. They also became a resource for families seeking less-toxic cleaning products.

Residents, in turn, told researchers that local bodegas sold pesticides and rodent poison that were either illegal or not meant for household use. In response, the Boston Public Health Commission launched a successful pesticide “buyback” program—akin to gun buybacks in other cities—under the Healthy Pest-Free Housing Initiative.

A Public Health Win

At the start of the IPM demonstration project in 2006, asthma rates in Boston public housing were nearly 24 percent, about the same as for all low-income Bostonians and well above the citywide rate of just under 10 percent. By 2010, asthma rates among BHA residents had plummeted to 13 percent, while rates citywide and among other low-income Bostonians barely budged.

At the start of the IPM demonstration project in 2006, asthma rates in Boston public housing were nearly 24 percent, about the same as for all low-income Bostonians and well above the citywide rate of just under 10 percent. By 2010, asthma rates among BHA residents had plummeted to 13 percent, while rates citywide and among other low-income Bostonians barely budged.

“When we had trained residents all over the city doing IPM with their neighbors and housing managers, and we had colleagues from around the country asking about our pest-control policies, that’s when I felt like: We’ve really got something here,” Henriquez says.

At housing conferences, Adamkiewicz and fellow researchers, along with Bennett-Fripp and BHA staff, gave presentations on IPM, which became the gold standard of pest control for housing authorities nationwide. “Among children, we saw asthma-related outcomes—such as attacks, hospital visits, and school absences—drop by more than half,” says Adamkiewicz. “If somebody invented a pill that could do that, it would be front-page news.”

Next Battle: Secondhand Smoke

In 2003, the Committee for Boston Public Housing surveyed BHA developments and found that asthma rates rose in tandem with smoking. That’s when Meena Carr, of the Washington Beech development in Boston’s Roslindale neighborhood, connected the smoke wafting through wall cavities and under doorways with the asthma that sometimes hospitalized her grandson, Malik, a toddler at the time. “We lived on the first floor. Nobody in my apartment smoked, but you would come in and think we all did,” Carr says.

But antismoking advocates like Carr didn’t have much ammunition until air sampling by Adamkiewicz and others showed that nonsmoking public housing residents breathed in secondhand smoke in concentrations equivalent to living with somebody who puffed one cigarette a day. “Once again,” says Adamkiewicz, “we were in the business of proving the obvious.”

By 2010, a working group of researchers, residents, and BHA staff began exploring a no-smoking policy for all of Boston public housing. Carr remembers confronting one smoker at a community meeting who vehemently opposed a smoking ban.

“I said, ‘Listen, you go right ahead and smoke,’” Carr says. “‘But wait until you have a child who wakes up in the middle of the night and says to you: I cannot breathe, my heart is beating like crazy. Then you will understand what I’m talking about.’”

Eventually, the neighbor dropped his opposition, as did many smokers in her development. In September 2012, the BHA banned smoking systemwide; at the time, it was the largest housing authority in the country to voluntarily go smoke-free. In partnership with the city’s health commission, the BHA offered free, on-site smoking-cessation programs to residents, including nicotine patches. Resident smokers didn’t have to quit, but smoking on BHA property or within 15 feet of the buildings could bring fines up to $250 and possible eviction. The smoking-cessation program remains in effect today.

The public health benefits have been dramatic. A year after the ban, concentrations of secondhand smoke pollutants dropped by half in smokers’ apartments, and by about 20 percent in apartments without smokers. Carr says her grandson, now a teenager, hasn’t suffered an asthma attack since the BHA went smoke-free. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has since proposed a nonsmoking rule for all public housing.

Still, enforcement of the ban has been spotty. A 2015 study by Adamkiewicz and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital found that while 82 percent of residents supported the ban, 51 percent said other residents routinely flout it. Despite anger at the rule breakers, residents were hesitant to report them because they realized that eviction could push people into a shelter or out on the streets.

From the Ground Up

How healthy could public housing be if the BHA could start over from scratch? In 2009, giant excavators ripped down the dark, dingy buildings of the old Washington Beech development. It was one of two BHA developments, along with Old Colony in South Boston, that would be rebuilt from the ground up as “green buildings,” LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design)-certified by the U.S. Green Building Council, thanks to $73 million from a 2008 HUD HOPE VI grant and the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, aka the federal stimulus.

Known for their environmental benefits, green building standards also call for paints, furniture, and carpets made with fewer toxic chemicals. Other potential green health benefits stem from improved heating systems and from tightening buildings to keep outside pollution out while better ventilation removes fumes and mold-causing moisture.

The redevelopments, completed in early 2012, were largely two-and three-story townhouses with graceful architectural touches like bay windows, awnings, and balustrades. The buildings were topped with solar panels, heated with ultraefficient boilers, and designed with both private and public green space and playgrounds. They faced tree-lined streets that stitched the development into the surrounding neighborhoods.

Better Health, Strong Community

As residents began moving into the new apartments, Adamkiewicz and Harvard Chan colleagues teamed up with the BHA and tenants to study the health impact of going green. In a 2015 study, they found that people in the green apartments reported better health and lower exposure to contaminants such as secondhand smoke, mold, chemicals, and pests. The residents suffered fewer “sick building” symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, and dizziness, and their children had fewer asthma attacks than did families in conventional housing. The study also found significant energy savings—and thus, cost savings—for water, electricity, and gas.

In anecdotal reports that were beyond the study’s formal scope, both residents and researchers say the new developments’ human scale and ample green space improved people’s sense of well-being and reduced their stress, something increasingly seen as a key ingredient of good health.

“I started talking more to people and getting to know my neighbors,” says longtime Washington Beech resident Westphalie Bruno. “It’s more peaceful. There’s more community.”

The Real Toxic Exposure: Chronic Poverty

Of course, green housing is just a start. Adamkiewicz’s 2015 study revealed that whether they lived in green or conventional housing, residents’ health was generally worse the longer they’d lived in public housing—a likely indicator of exposure to chronic poverty.

Put simply, as successful as targeted public health interventions may be, they can only chip away at social and economic injustice. Smoking rates rise as income drops. Impoverished neighborhoods are more polluted. Poor people own fewer cars to access doctors and have less money for prescriptions. Supermarkets selling affordable healthy food may be multiple bus rides away.

Compounding the problem, public housing in the U.S. is notoriously underfunded. “We don’t have the resources to provide direct services to residents. We’ve had staff cuts and layoffs,” says Lydia Agro, BHA chief of staff. The authority receives about 85 percent of the federal funding that it should be getting, according to HUD’s own funding formula, which is based on resident population, location, and building age.

Compounding the problem, public housing in the U.S. is notoriously underfunded. “We don’t have the resources to provide direct services to residents. We’ve had staff cuts and layoffs,” says Lydia Agro, BHA chief of staff. The authority receives about 85 percent of the federal funding that it should be getting, according to HUD’s own funding formula, which is based on resident population, location, and building age.

Adds John Kane, the BHA’s senior program coordinator, “For the past five years, four out of five residents who moved into BHA housing have come directly out of homelessness. They have complex problems and need a lot of wraparound services. But we’re the housing authority—we provide housing. If somebody comes in who is elderly and disabled, with substance abuse and mental health issues, we house them in our developments. Unfortunately, we don’t have mental health counselors on staff.”

Deconstructing Health Disparities

Adamkiewicz’s goal is to “deconstruct health disparities” and the web of causality that snags everything from individual health behaviors to broad social realities. He plans to continue this work outside of public housing through the new joint BU-Harvard Center for Research on Environmental and Social Stressors in Housing (CRESSH), backed by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In early 2016, Adamkiewicz and fellow CRESSH researchers began meeting with community groups representing Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood and the nearby hardscrabble city of Chelsea, Massachusetts, to recruit households for in-home studies and as part of a broader research agenda. Using a new fleet of cheap, real-time environmental sensors, and bridging health data with satellite mapping to measure things like green space, the researchers hope to discover how the health impacts of air pollution and other chemical exposures are shaped by income and race and modified by nonchemical factors such as temperature, noise, and other neighborhood characteristics.

Bennett-Fripp says that while such research can deliver tangible benefits, it doesn’t begin to address the deeper issues. “When you deal with one problem, it just means you can now attack another. There is always another problem, and then another one, and then another one.”

For his part, Adamkiewicz believes continued collaborations between researchers, citizens, nonprofits, and public agencies—delicate and thorny as these collaborations can be—could flip the script. Every policy and planning choice, he contends, is a chance to boost the conditions for health and well-being. “We need to focus on health disparities every time we talk about urban planning, or housing codes, or regional transportation plans, or how our hospitals are run,” he says. “Everybody has a role to play in solving these problems.”

But Adamkiewicz’s optimism is tempered by realism, and in the end, his words echo Bennett-Fripp’s. “Poverty,” he says, “is the underlying disease that we want to cure.”

Chris Berdik is a Boston-based science journalist.