Fellowship program spurs midcareer pros to solve big problems.

On many Mondays during the 1980s, Uche Amazigo took time off from teaching at the University of Nigeria to travel into her country’s rural villages and talk to women. A biologist and tropical disease specialist, Amazigo taught them about hygiene and nutrition and listened to their many health concerns.

On one of these trips she met a young pregnant woman named Agnes, who was suffering from a debilitating and disfiguring rash. The cause, Amazigo would discover, was the parasitic disease onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness. Abandoned by her husband because of her scars, Agnes was unable to afford the treatment that would stop her unrelenting itching and save her sight. Amazigo was not only moved to help this desolate victim, but she later joined what would become a more than 20-year campaign against a common but neglected infection that brings immense hardship for some of the world’s poorest people.

And the success of Amazigo’s river blindness control campaign is partly due to a decision she made at a key point early in her research: to step away from her fieldwork and spend a year (1991–92) as a research fellow in the Takemi Program in International Health at Harvard School of Public Health, supported by a grant to the Takemi Program from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. She credits that time—researching, taking courses, and discussing policy issues with the tight-knit and interdisciplinary community of fellows from around the world—with dramatically expanding the scope of her mission.

“The Takemi Program helped me put together my research findings in such a way that the scientific community would appreciate its importance,” Amazigo says. “It moved me from being a national scientist and researcher to an international health practitioner who is more effective on my own continent.”

Refocusing and recharging careers

For 30 years, the Takemi Program has offered midcareer professionals from health, economics, and policy fields “protected time” to take advantage of Harvard’s resources and the flexibility to pursue their own scientific questions. The goal is to develop leaders who will apply what they’ve learned to improve health in their home countries. Takemi Fellows have gone on to become health ministers, academic deans, heads of nongovernmental agencies, and social entrepreneurs around the world.

During her fellowship year, Amazigo focused her research on the burdens and social stigma caused by onchocerciasis skin lesions and itching—a cruel aspect of the disease ignored by treatment programs at the time. Her work helped spur the launch in 1995 of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s African Program for Onchocerciasis Control, which she joined and later led. During her time with the WHO, she was instrumental in developing and scaling up a community-directed strategy for distributing the antiparasitic drug Mectizan to the remote areas most at risk for the disease.

Amazigo was driven to ensure that those suffering from the disease had a voice in finding solutions. “I don’t think I would have had the courage to speak for them at international organizations if I had not passed through Takemi,” she says. “The program taught us that you must be able to argue for those who are not there but who deserve to be heard.”

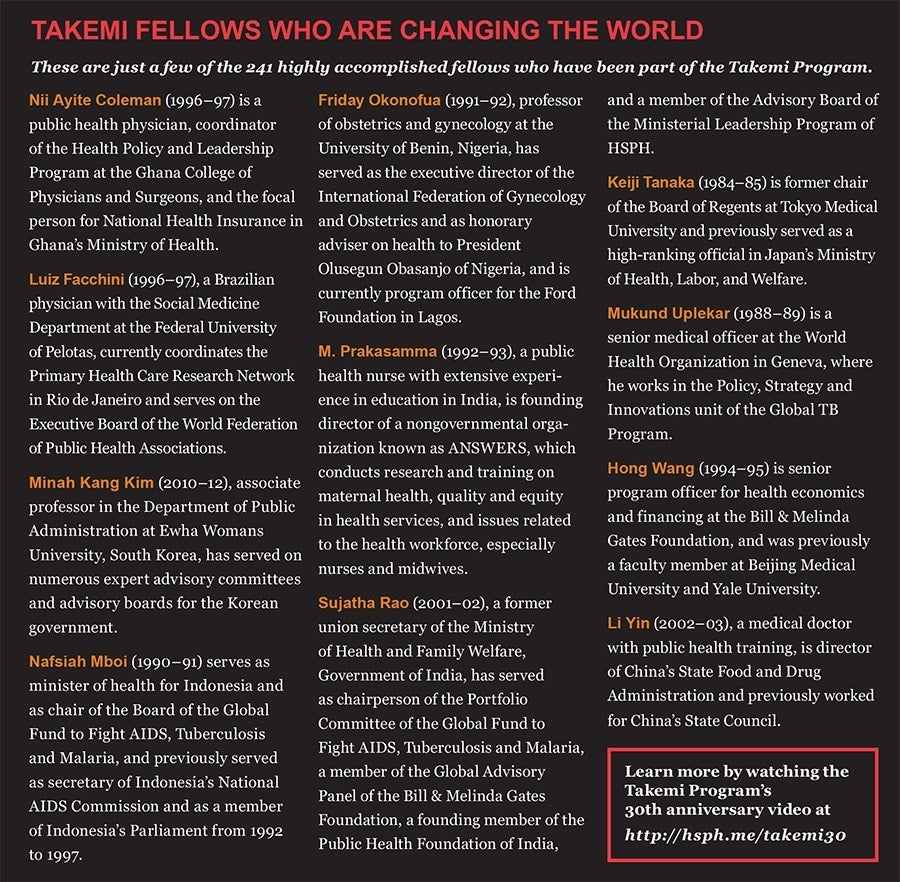

The Takemi Program was launched in 1983 by former HSPH Dean Howard Hiatt and by the late Taro Takemi, who at the time was president of the Japan Medical Association (JMA). Since then, 241 Takemi Fellows from 51 primarily low- and middle-income countries have taken part in the program. The JMA has been a key partner to the Takemi Program for many years.

The Takemi Program was launched in 1983 by former HSPH Dean Howard Hiatt and by the late Taro Takemi, who at the time was president of the Japan Medical Association (JMA). Since then, 241 Takemi Fellows from 51 primarily low- and middle-income countries have taken part in the program. The JMA has been a key partner to the Takemi Program for many years.

“There really is no other program like it in the world,” says Michael Reich, the program’s director and the Taro Takemi Professor of International Health Policy. Participation in the Takemi Program “moves people from a focused research perspective to the frontiers of knowledge and policy and gives them the confidence to produce change in their own institutions and in their own lives.”

Keizo Takemi, a politician, academic, and son of the program’s founder, used his time as a Takemi Fellow to collaborate with Reich and other Harvard faculty members on developing key content for Japan’s global health proposal at the G8 summit in 2008. The work helped shift the focus of global health policy toward strengthening health systems, both in Japan and worldwide, Reich says.

Changing how Japan thinks about health

The program is also changing the way Japan thinks about public health, adds Keizo Takemi. As Japanese fellows have returned home and taken on leadership roles in the public health community, they have been promoting an interdisciplinary approach to health policymaking.

For example, Marika Nomura-Baba, a current fellow sponsored by the JMA, has pursued both academic and fieldwork in public health at Japan’s Juntendo University and in Yemen. Now she’s using her fellowship year to analyze trends in global nutrition policy and how it might be moved up higher on Japan’s development agenda. Another fellow, Maryam Farvid, an associate professor at Iran’s Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, is eager to absorb all the latest research from HSPH’s Department of Nutrition, which she will apply back home in her work on food policy.

Fellows Shinichi Tomioka, a Japanese physician, and Tae-Jin Lee, a professor of public health at Seoul National University, are gaining perspective on their own countries’ health systems by exploring what does and doesn’t work in the United States and elsewhere. From courses and weekly seminar presentations by HSPH faculty to informal discussions with other fellows to following the ongoing debate over the Affordable Care Act, the experience has been illuminating, says Tomioka. “Takemi is like a candy store. There are so many things we can do and experience.”

The Takemi name carries prestige in global health circles, Reich adds, and fellows maintain their connections with the program and with each other after they leave. Nearly 80 fellows—about a third of past participants—returned to HSPH last fall for a symposium celebrating the Takemi Program’s 30th anniversary. According to HSPH Dean Julio Frenk, the Takemi Program’s approach—providing protected time for midcareer professionals, creating an interdisciplinary global community of scholars—exemplifies the School’s new strategy for public health education. “The Takemi Program has been hugely important for Harvard School of Public Health.”

And hugely important for public health generally. “Many of the fellows see each other at global health meetings around the world. Sometimes they meet a participant at one of these events and discover that they are both Takemi Fellows,” says Reich. “At almost any major health meeting around the world, you’ll find that those participating in key roles are Takemi Fellows.”

Amy Roeder is assistant editor of Harvard Public Health.

Photos: ©Ocean Photography / Veer.com, Bethany Versoy, Takemi Program, Kent Dayton / HSPH, Aubrey Calo / HSPH

Download a PDF of Time for thinking big