Findings open new window on the biology of the disease, offer inroads to new rapid diagnostic and vaccine approaches

For immediate release: Thursday, September 22, 2016

Boston, MA – Antibodies are one of the body’s first lines of defense against infection, but their role in tuberculosis (TB) has gone largely unstudied. Now, by harnessing a unique technology for rapidly analyzing human antibodies, a team of researchers led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard University has uncovered key differences in antibodies isolated from different groups of TB patients—findings that could spur new diagnostic tools and open a new scientific path towards an effective TB vaccine.

“Our work shatters some long-standing paradigms on TB,” explains co-senior author Sarah Fortune, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard Chan School and director of TB research at the Ragon Institute. “That means we’ll need to think differently about how the body develops natural immunity to the infection and how effective vaccines should be engineered.”

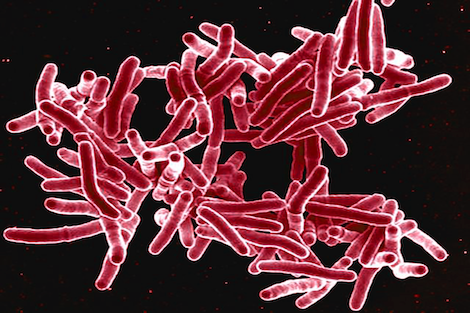

About a third of the world’s population carries the bacteria that cause TB, known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mtb. In 2014, nearly 10 million people worldwide became newly infected with Mtb and 1.5 million died. Although there are drugs that can treat the infection, drug-resistance is a pervasive problem and the most potent tool for long-term TB control—a vaccine—remains an elusive goal.

For decades, scientists have probed the roles of different immune cells in the body, mainly T-cells, in fighting off TB, but relatively little attention has been paid to another key form of immune defense: Y-shaped proteins known as antibodies. Fortune and her colleagues set out to answer a couple simple questions about antibodies in TB: First, are they different in people who are actively sick with TB versus those who can control the infection? If so, do those differences simply reflect disease state or do they play a functional role in shaping the course of TB infection?

Notably, studies of other infectious diseases have recently shown that antibodies exert an array of important functions, via the targets they recognize (using their forked front ends) and the signals they send (through their tails, which can bind to receptors on cells’ surfaces). For example, an innovative method for studying antibodies in a comprehensive, unbiased way shed new light on their roles in HIV. The approach, known as systems serology and pioneered by co-senior author Galit Alter and her colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Ragon Institute, provided a powerful tool for probing the biology of TB.

Fortune, Galit, and their colleagues teamed up with clinical researchers Cheryl Day of Emory University and Blanca Restrepo of the University of Texas in Houston, who contributed patient samples collected from two groups of TB patients: those with so-called latent infection, who are able to naturally control TB, and those with active disease, who lack such control. “The real power of this collaboration is that it allowed us to apply cutting-edge immunological tools to TB,” said Fortune.

By analyzing antibodies from the two TB patient groups and comparing them to each other, the Ragon-Harvard Chan School team was able to home in on some key differences. Although latently infected patients had lower overall levels of antibodies compared to those with active disease, their antibodies carried distinct molecular modifications—specifically unique sugar groups, called digalactose. On its own, the result has important implications because it could lay the foundation for a rapid diagnostic tool that distinguishes patients with active TB from those without.

But these sugary modifications are more than mere decorations; they also appear to boost the antibodies’ power to activate the immune system and propel Mtb-infected cells to kill the bacteria. Although these findings represent an important first step in unlocking the role of antibodies in TB infection, much more work is needed to understand the mechanisms through which these antibodies exert their differential effects.

Even still, the work opens up a tantalizing possibility. “One of the long-standing challenges in generating a TB vaccine is that we don’t really know how to build a vaccine that generates a robust T-cell response,” explains Fortune. “But now, with our findings suggesting an important role for antibodies, it casts light on a path toward TB vaccine development that is much more straightforward. That’s incredibly exciting.”

Other Harvard Chan School authors included co-lead authors Lenette L. Lu and Tracy Rosebrock, Constance Martin, and Vivian Leung.

“A functional role for antibodies in tuberculosis,” Lenette L. Lu, Amy W. Chung, Tracy Rosebrock, Musie Ghebremichael, Wen Han Yu, Patricia S. Grace, Matthew K. Schoen, Fikadu Tafesse, Constance Martin, Vivian Leung, Alison E. Mahan, Magdalena Sips, Manu Kumar, Jacquelynne Tedesco, Hannah Robinson, Elizabeth Tkachenko, Monia Draghi, Katherine J. Freedberg, Hendrik Streeck, Todd J. Suscovich, Douglas Lauffenburger, Blanca I. Restrepo, Cheryl Day, Sarah Fortune, Galit Alter, Cell, online Sept. 22, 2016

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia offerings.

For more information:

Marge Dwyer

617.432.8416

mhdwyer@hsph.harvard.edu

photo: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

###

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people’s lives—not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at Harvard Chan School teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.