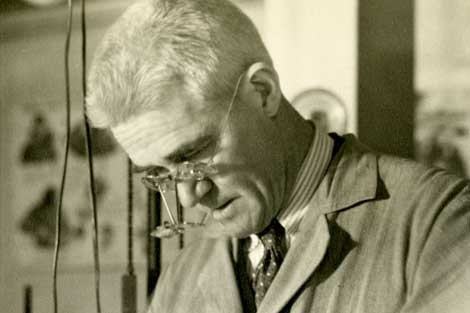

While academic couples are certainly more common than they once were, the two-career scholarly partnership is far from new, as reflected in the lives of Cecil Kent Drinker—who from 1935 to 1942 served as the School of Public Health’s first full-time dean—and his physician-researcher wife Katherine.

“Now we are settled in our apartment near the School, both of us studying medicine and more truly happy and contented than we have been in our lives. It passes all the dreams,” the future dean wrote to his bride shortly after their 1910 marriage, as they dove into their medical studies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The couple’s wedding gifts included $500 from one of Drinker’s aunts to support their research.

The Drinkers arrived at Harvard in 1916. Over the years, their joint projects would include an investigation of radium poisoning among women who painted luminous watch and clock dials. The study, now regarded as a classic in the field, revealed that the common practice of “pointing up”—running the paint brush between the lips to get a smooth point—led to ingestion of minute quantities of radioactive radium that were incorporated into the facial bones, causing necrosis of the jaw. William B. Castle, a distinguished hematologist who served on the faculty of Harvard Medical School, was a third collaborator.

Cecil Drinker assumed the deanship of Harvard School of Public Health at the age of 48. (The previous dean, David Linn Edsall, had divided his time between the Harvard Medical School and HSPH.) Significant milestones of the Drinker deanship included expansion of the School from 50 to 95 students a year, admission of women as degree candidates, and a broadening of the School’s curriculum to include lectures in sociology and a course in medical writing taught by Katherine Drinker, who served as a research assistant and instructor in public health practice. During his tenure, Cecil Drinker also recruited his younger brother Philip, who would go on to fame as the inventor of the iron lung, a device that made it possible for polio victims to breathe normally.

After retirement from teaching in 1947, Cecil Drinker remained intellectually engaged, building laboratories in his homes in Brookline and Falmouth, Massachusetts. But his research interests failed to sustain him after the death of his wife and longtime colleague. He died in 1956, just weeks after Katherine succumbed to leukemia.

Is there an event, person, or discovery in Harvard School of Public Health history that you’d like to read about? Send your suggestions to Centennial@hsph.harvard.edu.