May 25, 2018 — A series of 18 portraits of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health community members was installed recently in the Kresge Atrium. The individuals featured in the project, called “Facing Forward,” include faculty, staff, students, and academic appointees. Each print is paired with a narrative written by the subject, describing their struggles, inspirations, and journey into public health (see below for gallery).

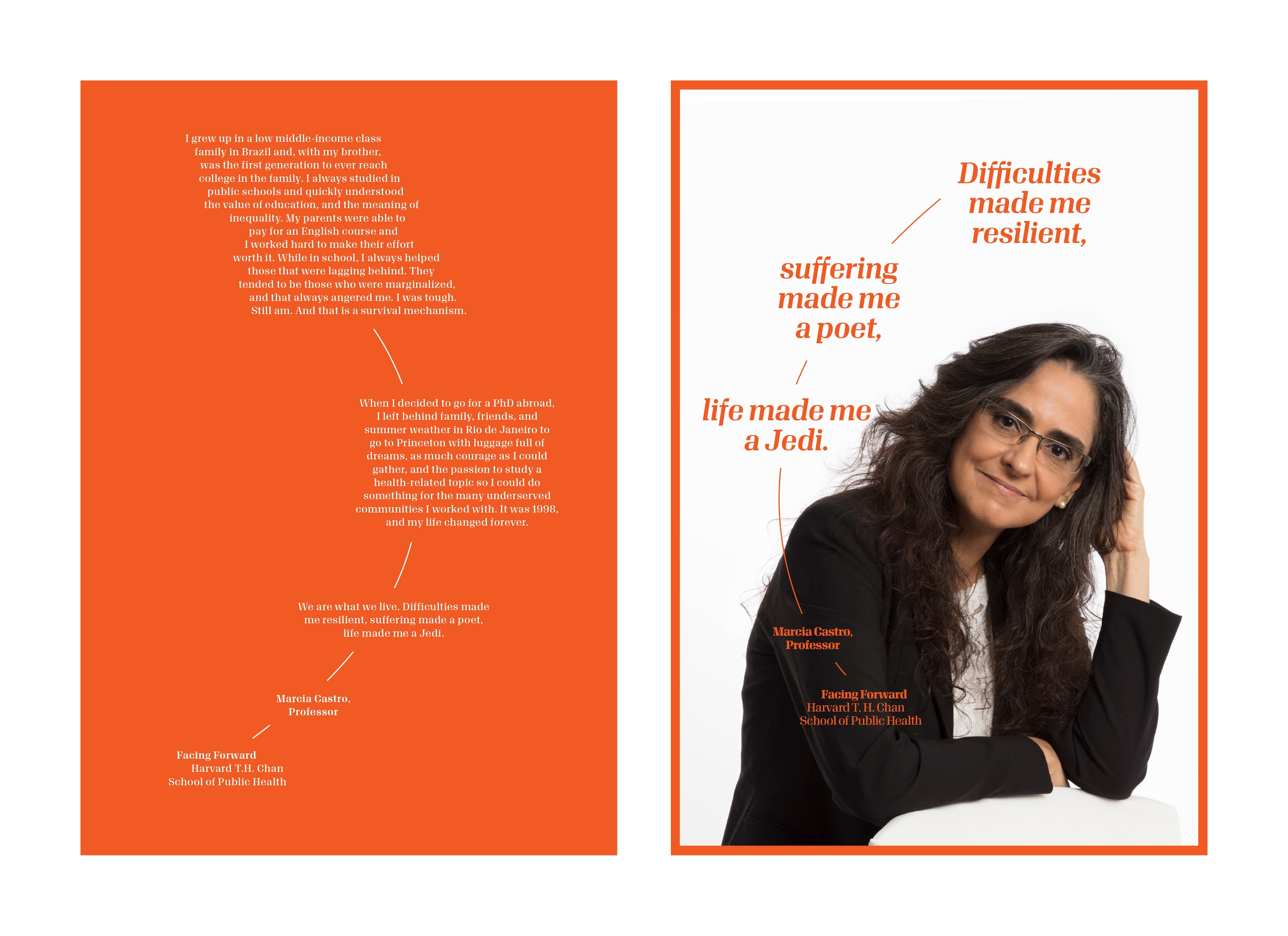

In her narrative, Marcia Castro, professor of demography, wrote, “We are what we live. Difficulties made me resilient, suffering made a poet, life made me a Jedi.”

Dean Michelle Williams celebrated the project’s installation in her remarks at the School’s Spring Reception on May 21. She said that Facing Forward joins the Ghost Portraits exhibition—photographs honoring African American and Native American public health notables which were on display in the Atrium for the past year—and the Pride flags recently installed at the School, in honoring the community’s “impressive diversity.”

Facing Forward is displayed on the first and second floors of the Kresge Atrium. The Ghost Portraits will be installed in a new location on the ground floor of Kresge.

Celebrating who we are

The idea for Facing Forward came from Kristina Gravellese, a senior recruiter in human resources, and was launched by the Kresge Atrium Task Force, a school-wide committee organized to rethink this central, communal space. The group solicited nominations for portrait subjects from the community, and chose from approximately 50 entries. They worked with photographer Adam Mastoon and graphic design studio Morcos Key.

Gravellese said that she envisioned the project as a way to break down barriers at the School and “Celebrate who we are.”

The subjects represent a broad cross section of voices at the School, wrote Meredith Rosenthal, senior associate dean for academic affairs and C. Boyden Gray Professor of Health Economics and Policy in an email announcement to the community. They amplify the wide-ranging “interests, identities, and experiences within our community while creating a more inclusive environment for all who pass through the heart of our campus.”

Looking up at his portrait during the reception, security guard Solomon Zerihun deflected compliments. But he smiled as he reflected on the School’s efforts to reflect the diversity of the community. “This project is fantastic,” he said.

Photos: Sarah Sholes (article), Adam Mastoon (gallery)

See text versions of the narratives

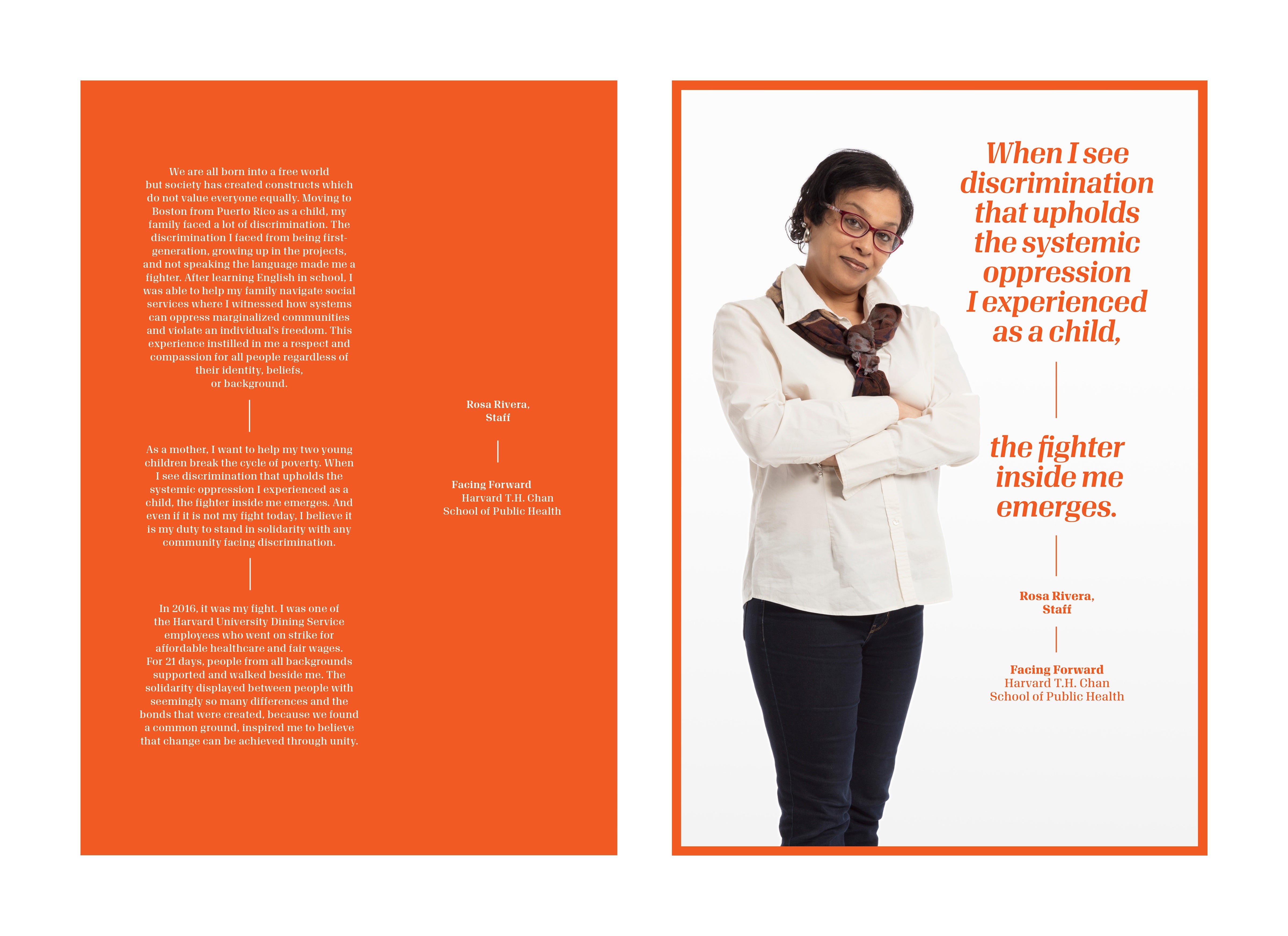

Rosa Rivera

We are all born into a free world but society has created constructs which do not value everyone equally. Moving to Boston from Puerto Rico as a child, my family faced a lot of discrimination. The discrimination I faced from being first-generation, growing up in the projects, and not speaking the language made me a fighter. After learning English in school, I was able to help my family navigate social services where I witnessed how systems can oppress marginalized communities and violate an individual’s freedom. This experience instilled in me a respect and compassion for all people regardless of their identity, beliefs, or background.

As a mother, I want to help my two-young-children break the cycle of poverty. When I see discrimination that upholds the systemic oppression I experienced as a child, the fighter inside me emerges. And even if it is not my fight, today, I believe it is my duty to stand in solidarity with any community facing discrimination.

In 2016, it was my fight. I was one of the Harvard University Dining Service employees who went on strike for affordable healthcare and fair wages. For 21 days, people from all backgrounds supported and walked beside me. The solidarity displayed between people with seemingly so many differences and the bonds that were created, because we found a common ground, inspired me to believe that change can be achieved through unity.

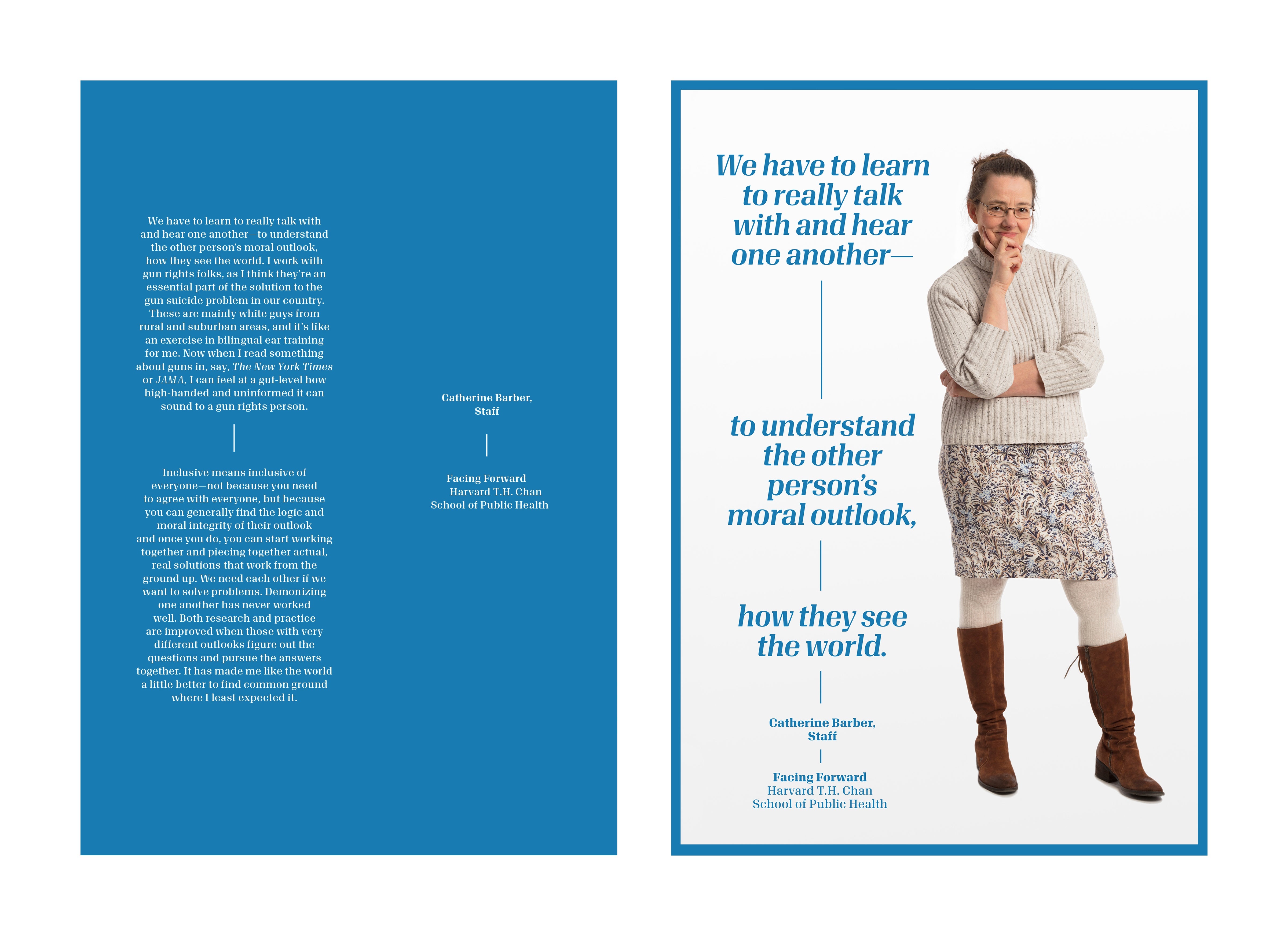

Catherine Barber

We have to learn to really talk with and hear one another – to understand the other person’s moral outlook, how they see the world. I work with gun rights folks, as I think they’re an essential part of the solution to the gun suicide problem in our country. These are mainly white guys from rural and suburban areas, and it’s like an exercise in bilingual ear training for me. Now when I read something about guns in, say, The New York Times or JAMA, I can feel at a gut-level how high-handed and uninformed it can sound to a gun rights person. Inclusive means inclusive of everyone – not because you need to agree with everyone, but because you can generally find the logic and moral integrity of their outlook and once you do, you can start working together and piecing together actual, real solutions that work from the ground up. We need each other if we want to solve problems. Demonizing one another has never worked well. Both research and practice are improved when those with very different outlooks figure out the questions and pursue the answers together. It has made me like the world a little better to find common ground where I least expected it.

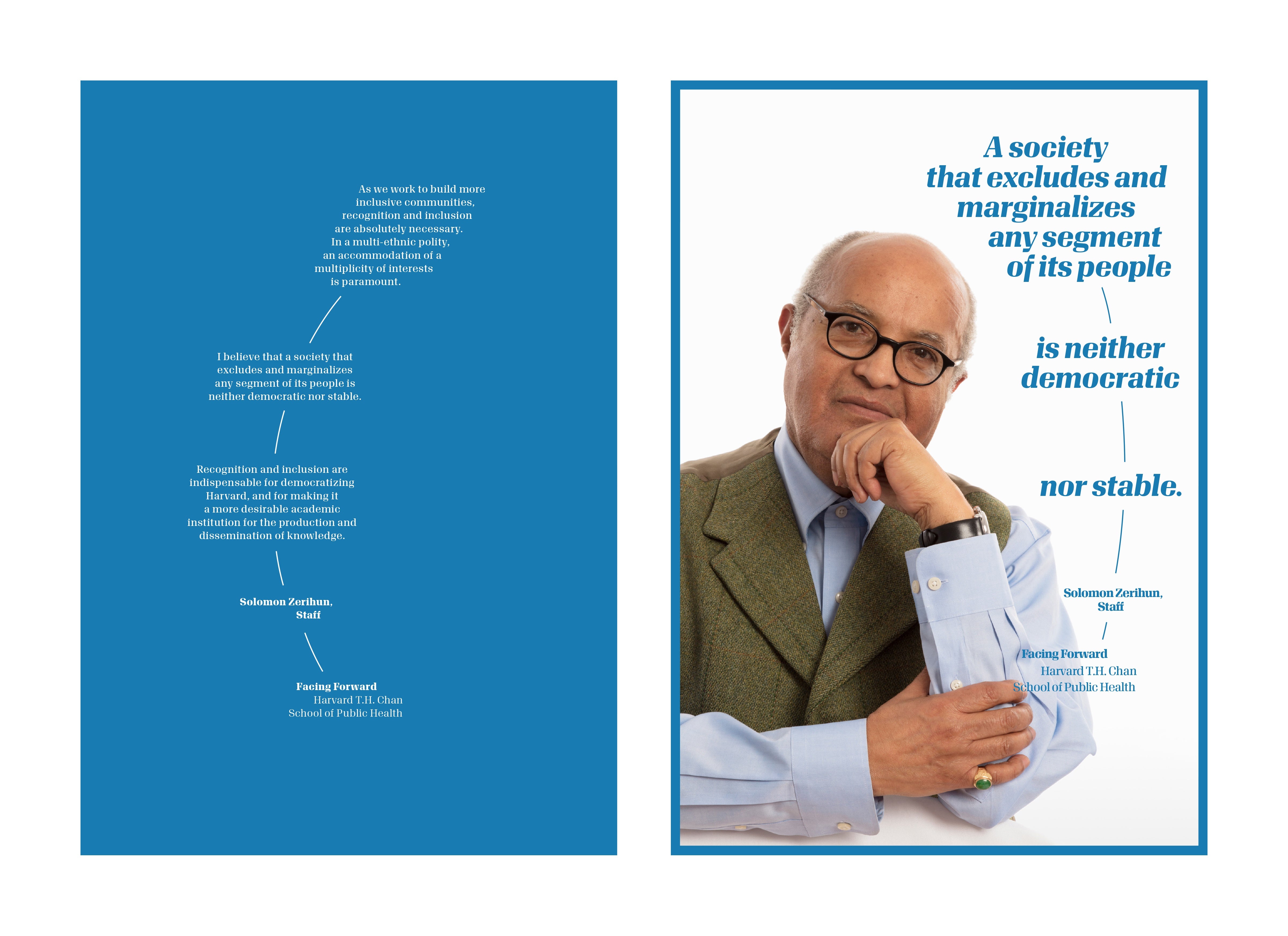

Solomon Zerihun

As we work to build more inclusive communities, recognition and inclusion are absolutely necessary. In a multi-ethnic polity, an accommodation of a multiplicity of interests is paramount. I believe that a society that excludes and marginalizes any segment of its people is neither democratic nor stable. Recognition and inclusion are indispensable for democratizing Harvard, and for making it a more desirable academic institution for the production and dissemination of knowledge.

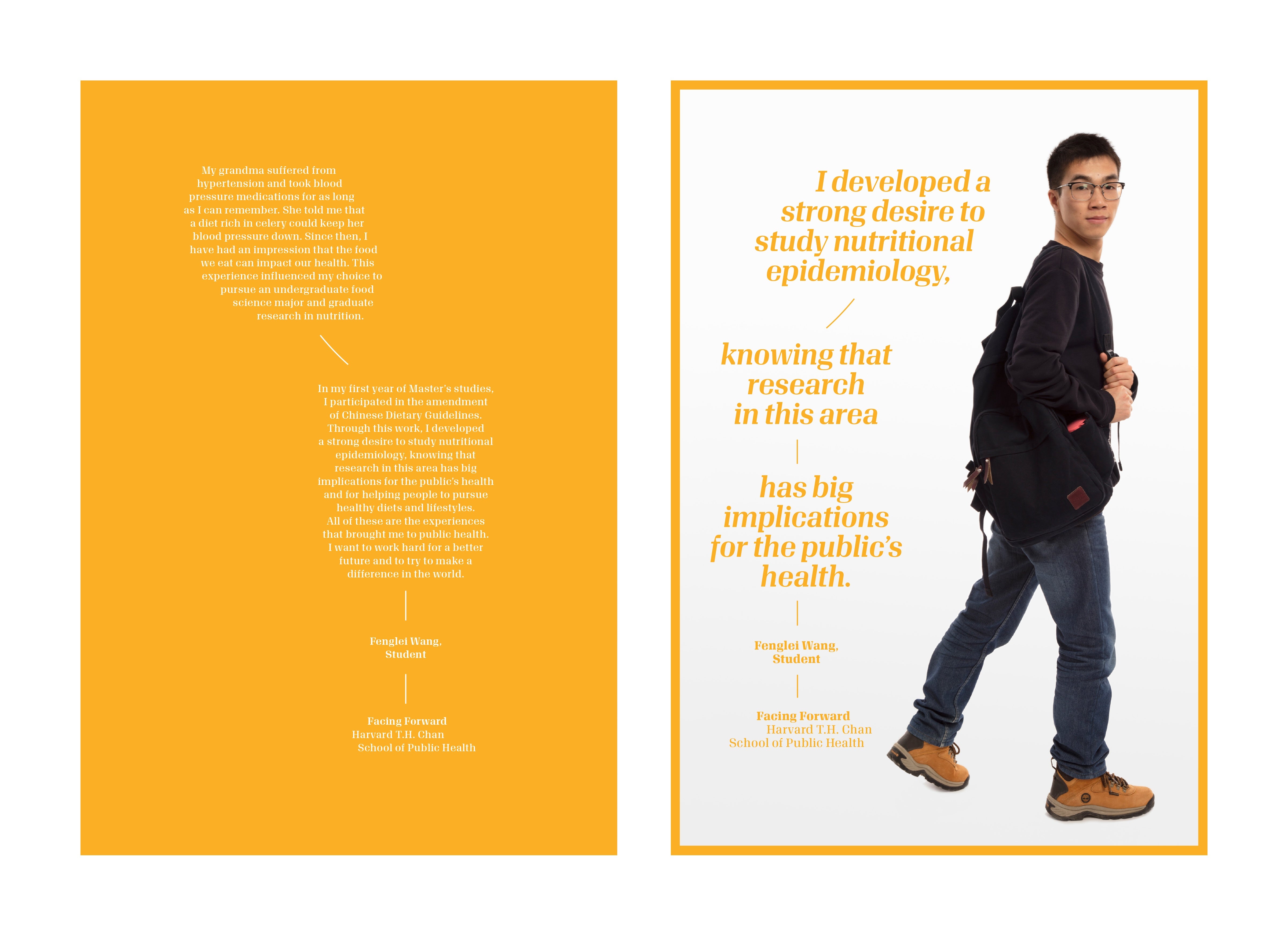

Fenglei Wang

My grandma suffered from hypertension and took blood pressure medications for as long as I can remember. She told me that a diet rich in celery could keep her blood pressure down. Since then, I have had an impression that the food we eat can impact our health. This experience influenced my choice to pursue an undergraduate food science major and graduate research in nutrition. In my first year of Master’s studies, I participated in the amendment of Chinese Dietary Guideline. Through this work, I developed a strong desire to study nutritional epidemiology, knowing that research in this area has big implications for the public’s health and for helping people to pursue healthy diets and lifestyles. All of these are the experiences that brought me to public health. I want to work hard for a better future and to try to make a difference in the world.

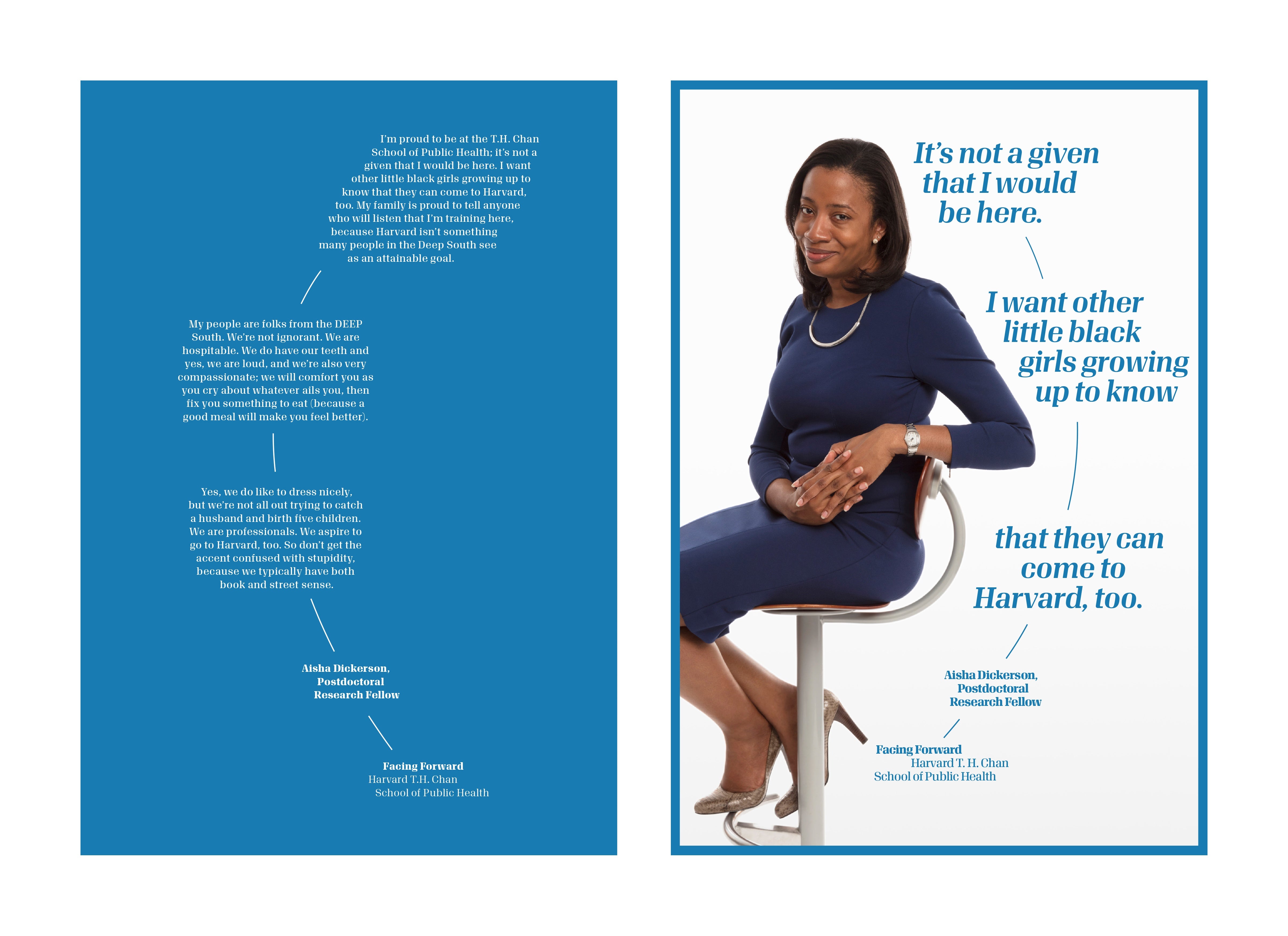

Aisha Dickerson

I’m proud to be at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health; it’s not a given that I would be here. I want other little black girls growing up to know that they can come to Harvard, too. My family is proud to tell anyone who will listen that I’m training here, because Harvard isn’t something many people in the Deep South see as an attainable goal.

My people are folks from the DEEP South. We’re not ignorant. We are hospitable. We do have our teeth and yes, we are loud, and we’re also very compassionate; we will comfort you as you cry about whatever ails you, then fix you something to eat (because a good meal will make you feel better). Yes, we do like to dress nicely, but we’re not all out trying to catch a husband and birth five children. We are professionals. We aspire to go to Harvard, too. So don’t get the accent confused with stupidity, because we typically have both book and street sense.

Marcia Castro

I grew up in a low middle-income class family in Brazil and, with my brother, was the first generation to ever reach college in the family. I always studied in public schools and quickly understood the value of education, and the meaning of inequality. My parents were able to pay for an English course and I worked hard to make their effort worth it. While in school, I always helped those that were lagging behind. They tended to be those marginalized, and that always angered me. I was tough. Still am. And that is a survival mechanism.

When I decided to go for a PhD abroad, I left behind family, friends, and summer weather in Rio de Janeiro to go to Princeton with luggage full of dreams, as much courage as I could gather, and the passion to study a health-related topic so I could do something for the many underserved communities I worked with. It was 1998, and my life changed forever.

We are what we live. Difficulties made me resilient, suffering made a poet, life made me a Jedi.

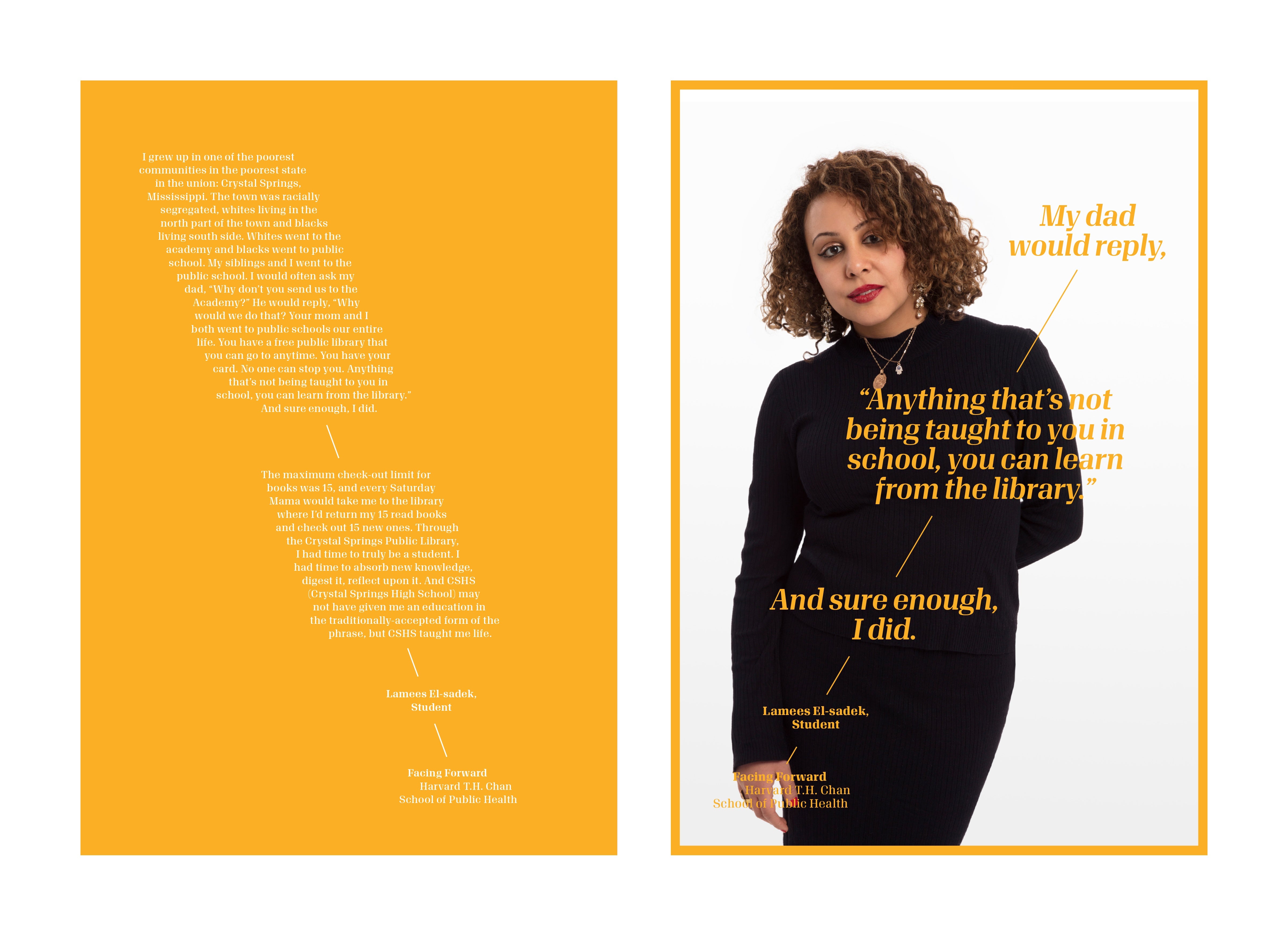

Lamees El-sadek

I grew up in one of the poorest communities in the poorest state in the union: Crystal Springs, Mississippi. The town was racially segregated, whites living in the north part of the town and blacks living south side. Whites went to the academy and blacks went to public school. My siblings and I went to the public school. I would often ask my dad, “Why don’t you send us to the Academy?” He would reply, “Why would we do that? Your mom and I both went to public schools our entire life. You have a free public library that you can go to anytime. You have your card. No one can stop you. Anything that’s not being taught to you in school, you can learn from the library.” And sure enough, I did. The maximum check-out limit for books was 15, and every Saturday Mama would take me to the library where I’d return my 15 read books and check out 15 new ones. Through the Crystal Springs Public Library, I had time to truly be a student. I had time to absorb new knowledge, digest it, reflect upon it. And CSHS (Crystal Springs High School) may not have given me an education in the traditionally-accepted form of the phrase, but CSHS taught me life.

Rebekka Lee

Like so many people I’ve met at this school, I feel like I stumbled my way into public health. In college, I quickly gravitated to psychology after taking a psychology of racism class. Each week, I deepened my understanding of the unearned privileges I benefited from given my whiteness. There were tears, there was guilt, but most of all, there was growth that would push me to find a career where I could challenge racism. It is particularly important that I name this privilege as I work on public health interventions in communities of color. I must acknowledge what I don’t know and strive towards racial equity in my daily actions.

My queerness also shapes who I am. I think of the decade plus that I’ve been here and look back fondly at how this part of my identity has grown. I think of how I rehearsed the way I would come out to my first boss, when I was working as a staff assistant early on. So much has changed. Now the gay women from my doctoral program have seen each other through so many life milestones and have become the fabric of my community.

These identities are a big part of how I see the world and how I’ve gotten where I am today.

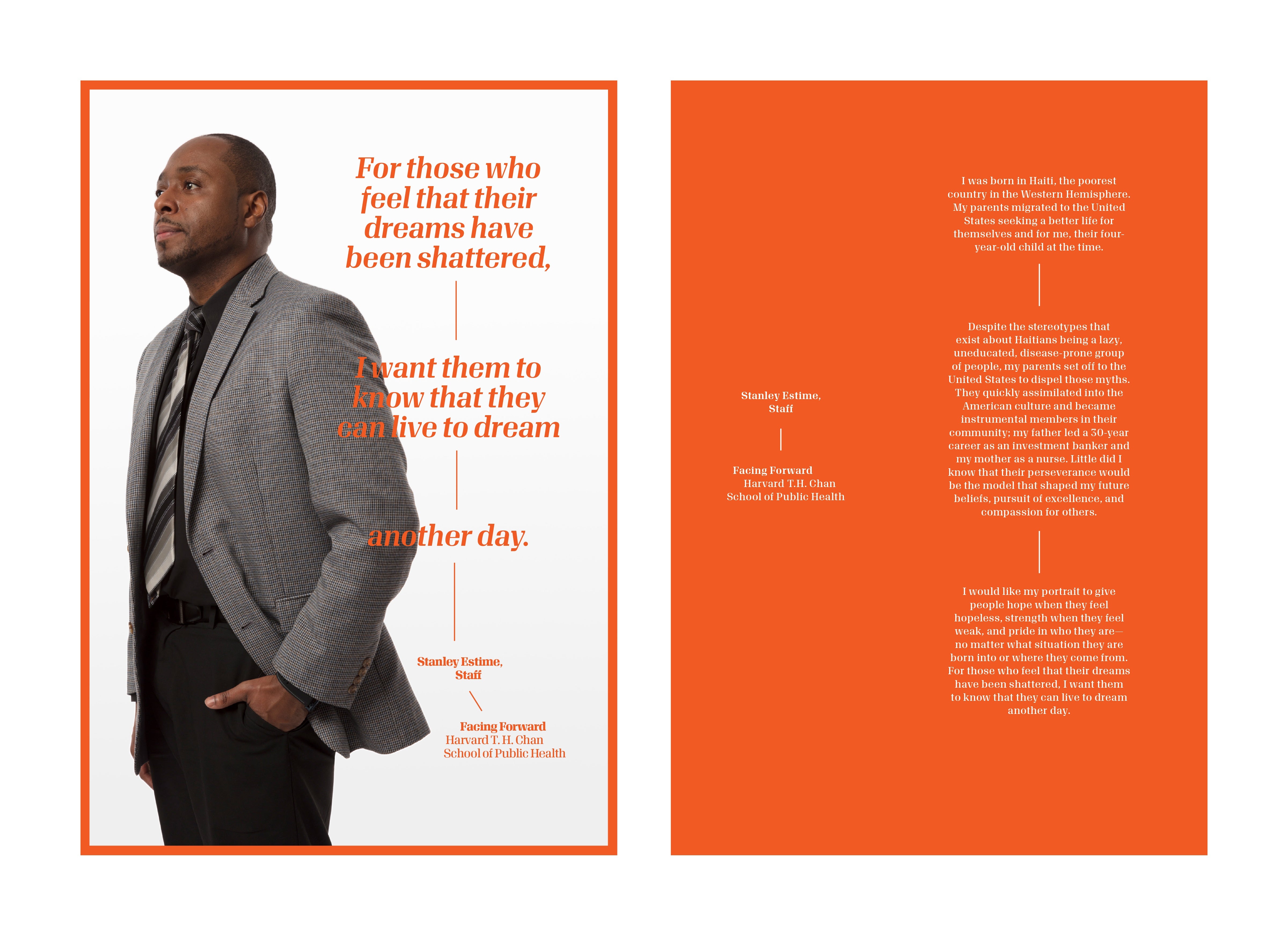

Stanley Estime

I was born in Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. My parents migrated to the United States seeking a better life for themselves and for me, their four-year-old child at the time. Despite the stereotypes that exist about Haitians being a lazy, uneducated, disease-prone group of people, my parents set off to the United States to dispel those myths. They quickly assimilated into the American culture and became instrumental members in their community; my father led a 30-year career as an investment banker and my mother as a nurse. Little did I know that their perseverance would be the model that shaped my future beliefs, pursuit of excellence, and compassion for others.

I would like my portrait to give people hope when they feel hopeless, strength when they feel weak, and pride in who they are – no matter what situation they are born into or where they come from. For those who feel that their dreams have been shattered, I want them to know that they can live to dream another day.

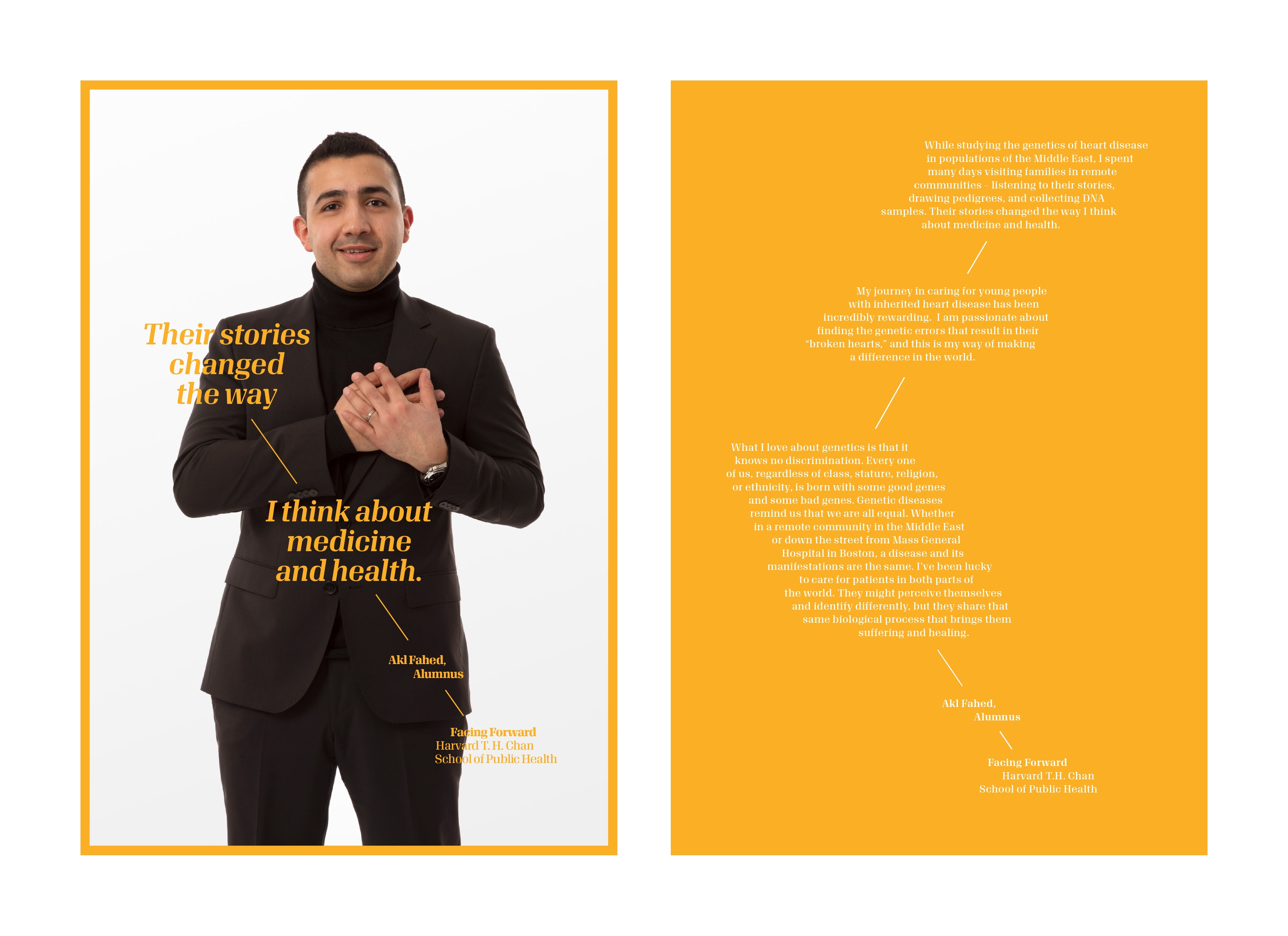

Akl Fahed

While studying the genetics of heart disease in populations of the Middle East, I spent many days visiting families in remote communities – listening to their stories, drawing pedigrees, and collecting DNA samples. Their stories changed the way I think about medicine and health.

My journey in caring for young people with inherited heart disease has been incredibly rewarding. I am passionate about finding the genetic errors that result in their “broken hearts,” and this is my way of making a difference in the world.

What I love about genetics is that it knows no discrimination. Every one of us, regardless of class, stature, religion, or ethnicity, is born with some good genes and some bad genes. Genetic diseases remind us that we are all equal. Whether in a remote community in the Middle East or down the street from Mass General Hospital in Boston, a disease and its manifestations are the same. I’ve been lucky to care for patients in both parts of the world. They might perceive themselves and identify differently, but they share that same biological process that brings them suffering and healing.

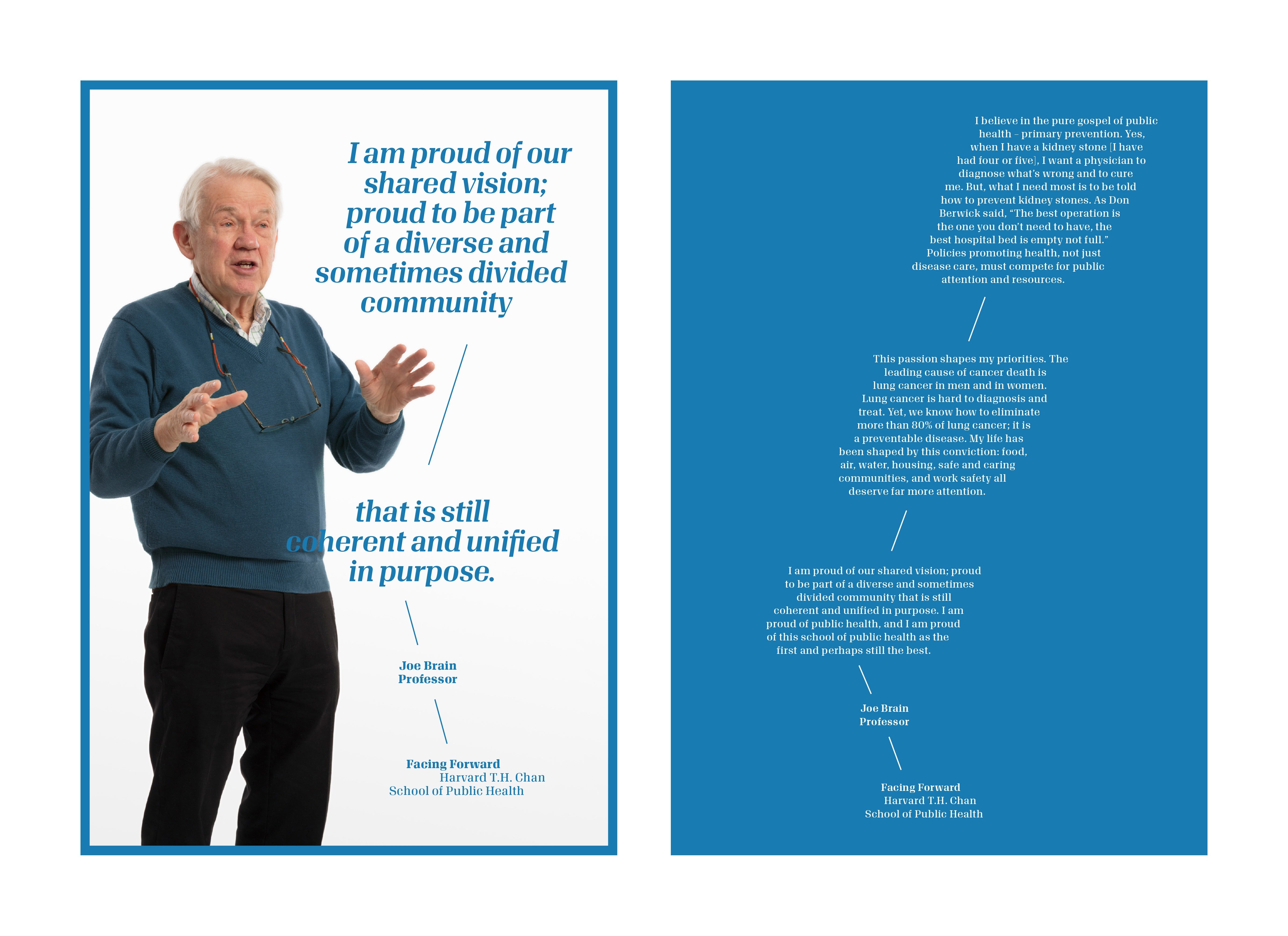

Joe Brain

I believe in the pure gospel of public health – primary prevention. Yes, when I have a kidney stone [I have had 4 or 5], I want a physician to diagnose what’s wrong and to cure me. But, what I need most is to be told how to prevent kidney stones. As Don Berwick said, “The best operation is the one you don’t need to have, the best hospital bed is empty not full.” Policies promoting health, not just disease care, must compete for public attention and resources.

This passion shapes my priorities. The leading cause of cancer death is lung cancer in men and in women. Lung cancer is hard to diagnosis and treat. Yet, we know how to eliminate more than 80% of lung cancer; it is a preventable disease. My life has been shaped by this conviction: Food, air, water, housing, safe and caring communities, and work safety all deserve far more attention.

I am proud of our shared vision; proud to be part of a diverse and sometimes divided community that is still coherent and unified in purpose.

I am proud of public health, and I am proud of this school of public health as the first and perhaps still the best.

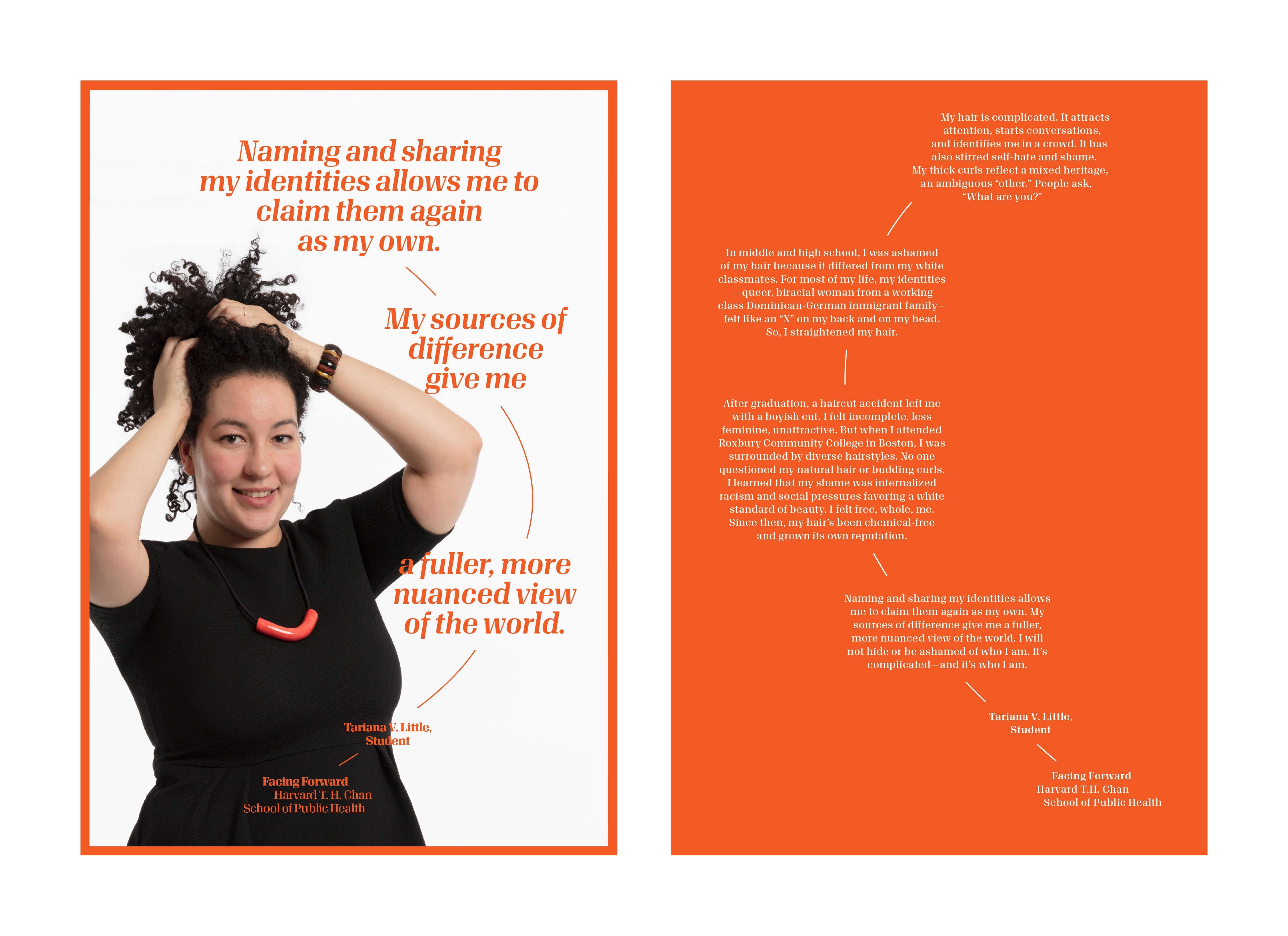

Tariana V. Little

My hair is complicated. It attracts attention, starts conversations, and identifies me in a crowd. It has also stirred self-hate and shame. My thick curls reflect a mixed heritage, an ambiguous “other.” People ask, “What are you?”

In middle and high school, I was ashamed of my hair because it differed from my white classmates. For most of my life, my identities – queer, biracial woman from a working class Dominican-German immigrant family – felt like an “X” on my back and on my head. So, I straightened my hair.

After graduation, a haircut accident left me with a boyish cut. I felt incomplete, less feminine, unattractive. But when I attended Roxbury Community College in Boston, I was surrounded by diverse hairstyles. No one questioned my natural hair or budding curls. I learned that my shame was internalized racism and social pressures favoring a white standard of beauty. I felt free, whole, me. Since then, my hair’s been chemical-free and grown its own reputation.

Naming and sharing my identities allows me to claim them again as my own. My sources of difference give me a fuller, more nuanced lens of the world. I will not hide or be ashamed of who I am. It’s complicated – and it’s who I am.

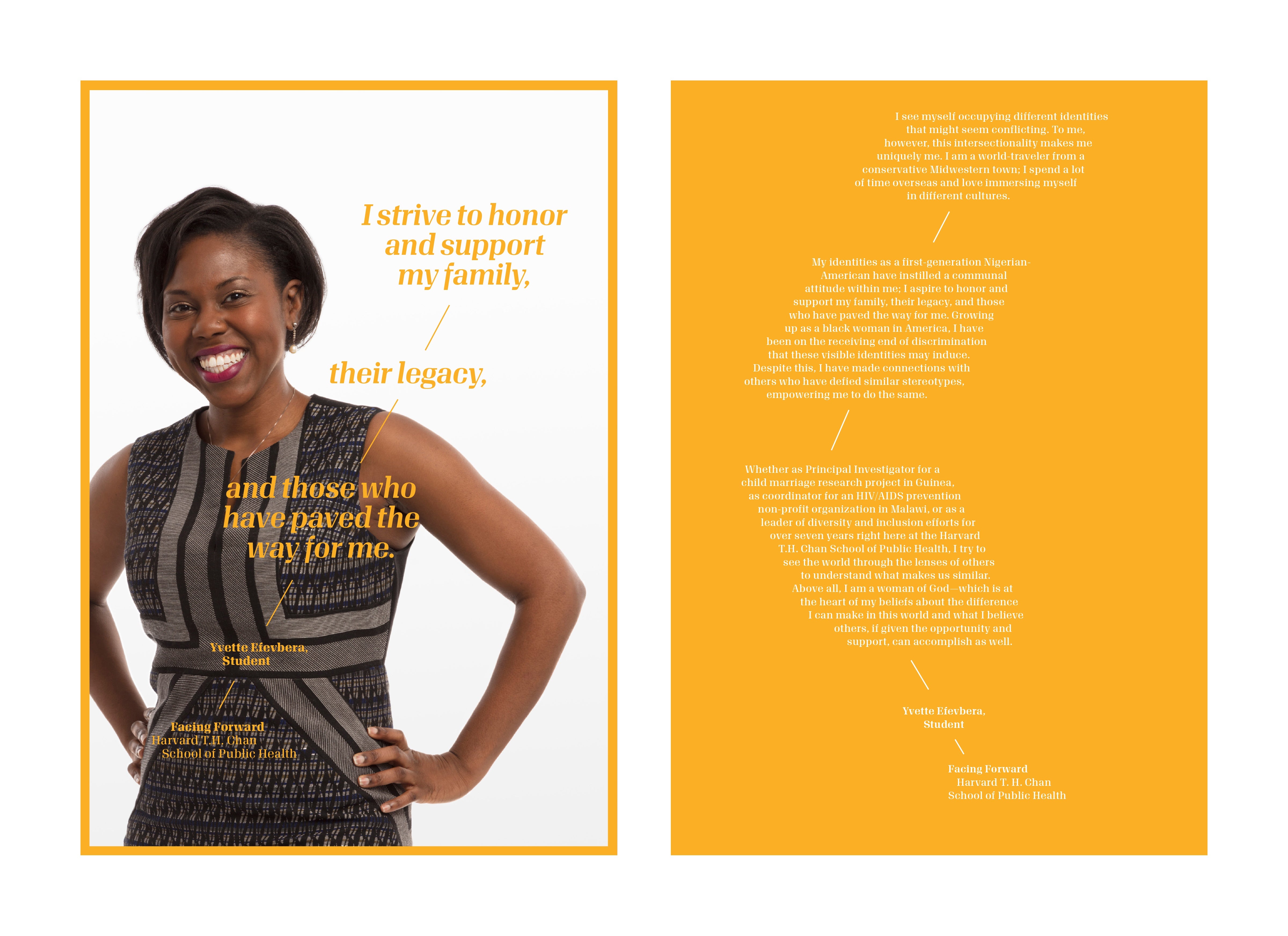

Yvette Efevbera

I see myself occupying different identities that might seem conflicting. To me, however, this intersectionality makes me uniquely me. I am a world-traveler from a conservative Midwestern town; I spend a lot of time overseas and love immersing myself in different cultures. My identities as a first-generation Nigerian-American have instilled a communal attitude within me; I aspire to honor and support my family, their legacy, and those who have paved the way for me. Growing up as a black woman in America, I have been on the receiving end of discrimination that these visible identities may induce. Despite this, I have made connections with others who have defied similar stereotypes, empowering me to do the same. Whether as Principal Investigator for a child marriage research project in Guinea, as coordinator for an HIV/AIDS prevention non-profit organization in Malawi, or as a leader of diversity and inclusion efforts for over seven years right here at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, I try to see the world through the lenses of others to understand what makes us similar. Above all, I am a woman of God – which is at the heart of my beliefs about the difference I can make in this world and what I believe others, if given the opportunity and support, can accomplish as well.

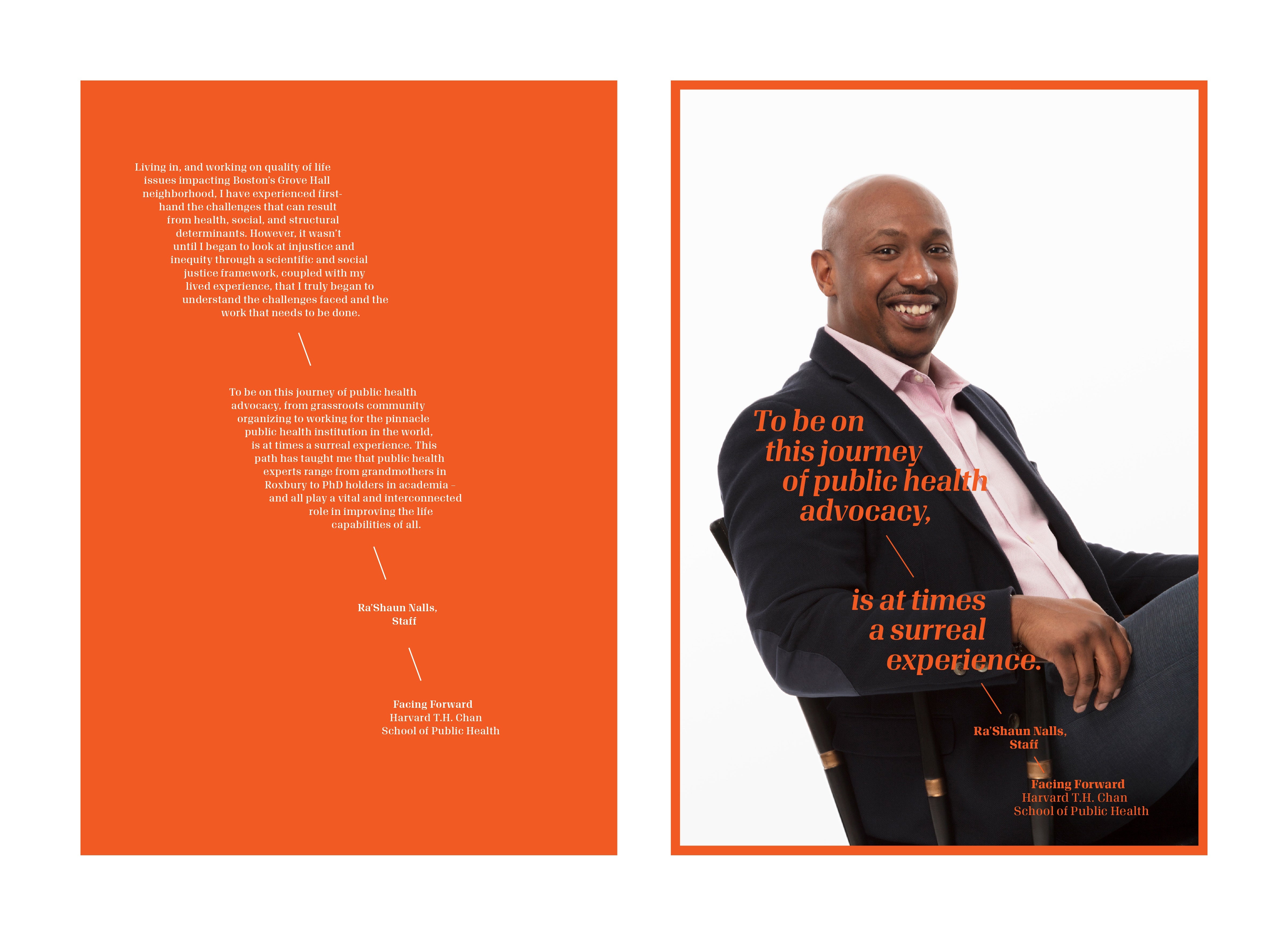

Ra’Shaun Nalls

Living in, and working on quality of life issues impacting Boston’s Grove Hall neighborhood, I have experienced first-hand the challenges that can result from health, social, and structural determinants. However, it wasn’t until I began to look at injustice and inequity through a scientific and social justice framework, coupled with my lived experience, that I truly began to understand the challenges faced and the work that needs to be done. To be on this journey of public health advocacy, from grassroots community organizing to working for the pinnacle public health institution in the world, is at times a surreal experience. This path has taught me that public health experts range from grandmothers in Roxbury to PhD holders in academia – and all play a vital and interconnected role in improving the life capabilities of all.

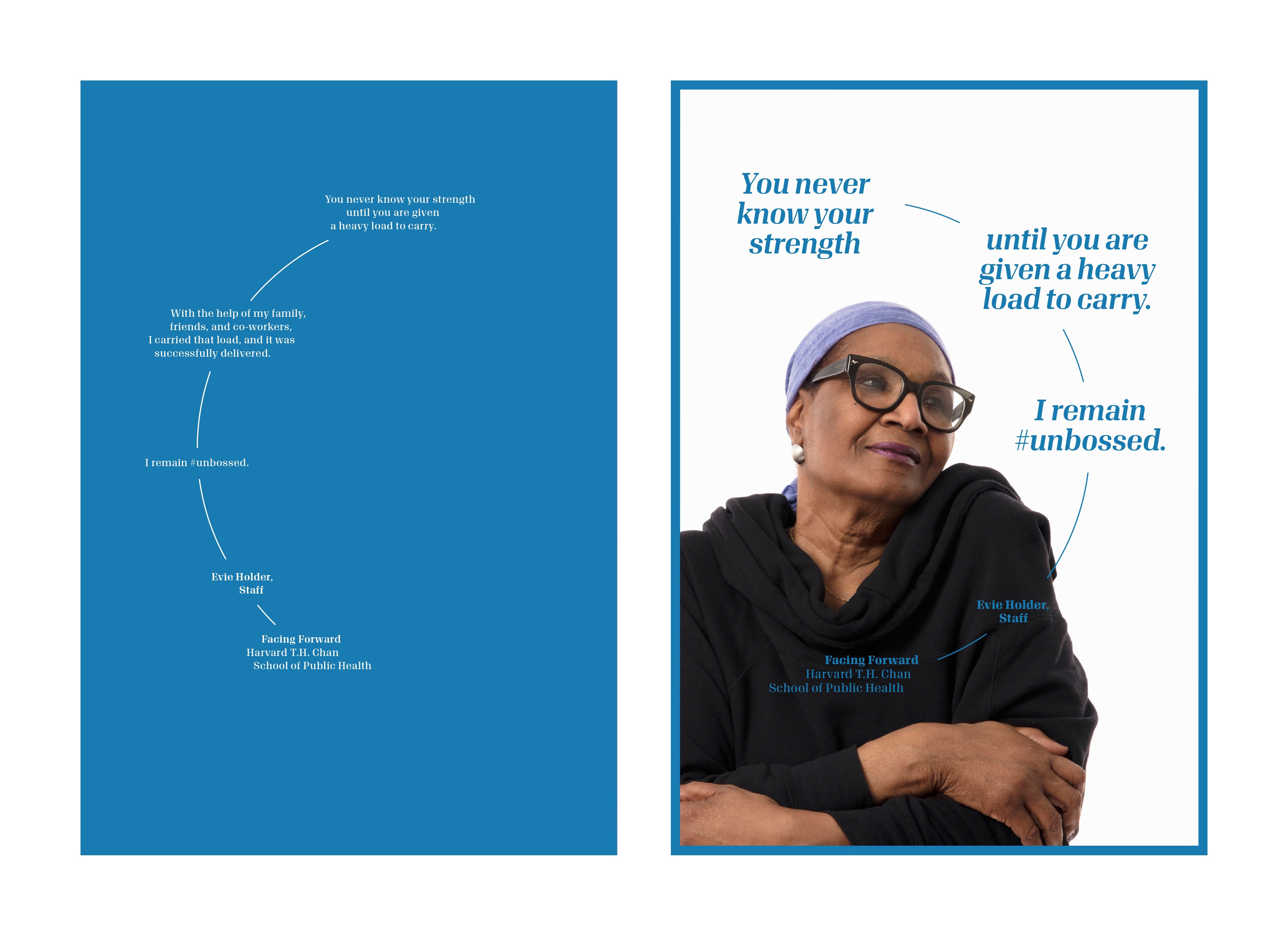

Evie Holder

You never know your strength until you are given a heavy load to carry. With the help of my family, friends, co-workers, I carried that load, and it was successfully delivered. I remain #unbossed.

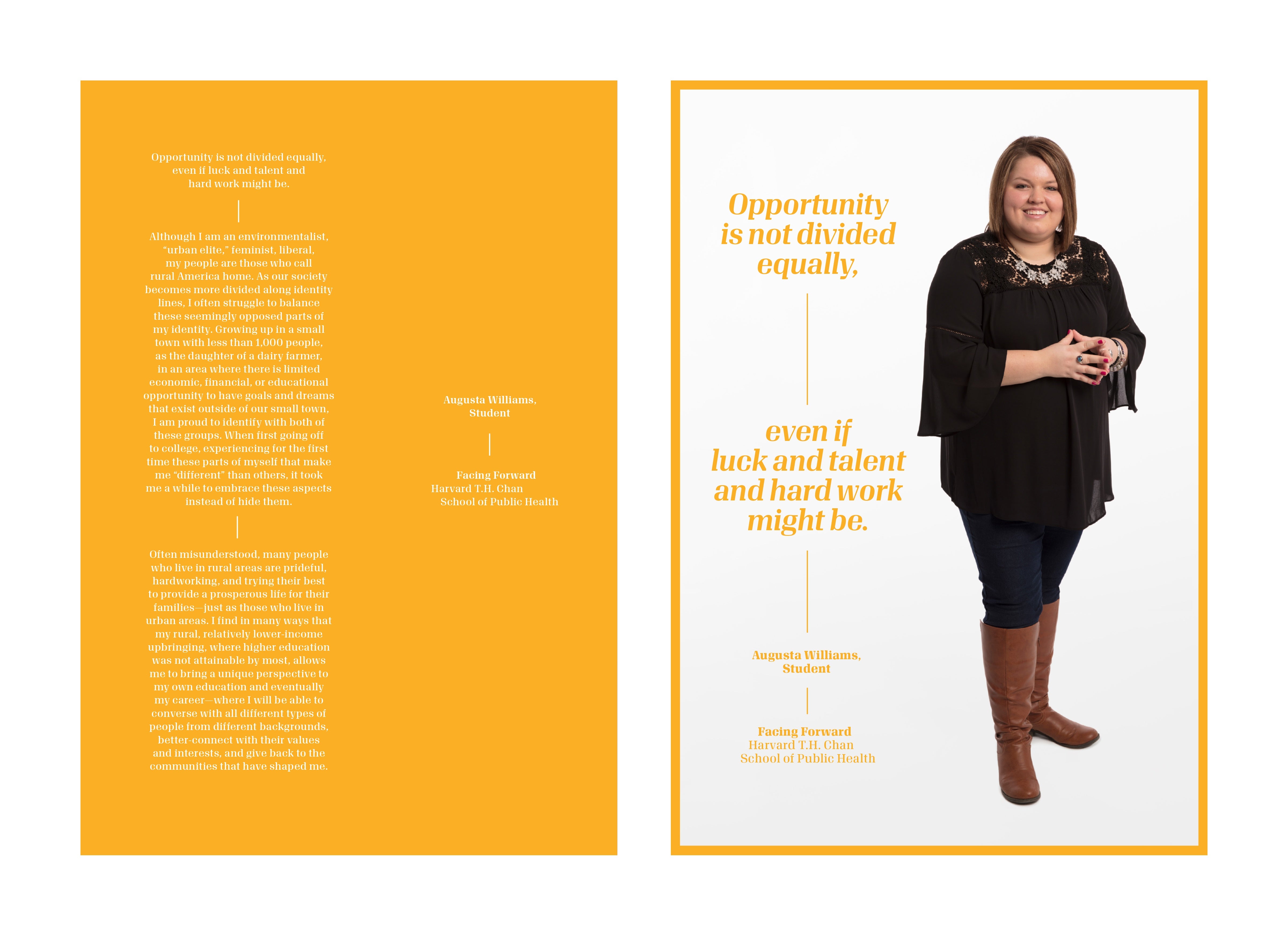

Augusta Williams

Opportunity is not divided equally, even if luck and talent and hard work might be.

Although I am an environmentalist, “urban elite,” feminist, liberal, my people are those who call rural America home. As our society becomes more divided along identity lines, I often struggle to balance these seemingly opposed parts of my identity. Growing up in a small town with less than 1,000 people, as the daughter of a dairy farmer, in an area with there is limited economic, financial, or educational opportunity to have goals and dreams that exist outside of our small town, I am proud to identify with both of these groups. When first going off to college, experiencing for the first time these parts of myself that make me “different” than others, it took me a while to embrace these aspects instead of hide them. Often misunderstood, many people who live in rural areas are prideful, hardworking, and trying their best to provide a prosperous life for their families – just as those who live in urban areas. I find in many ways that my rural, relatively lower-income upbringing, where high education was not attainable by most, allows me to bring a unique perspective to my own education and eventually my career – where I will be able to converse with all different types of people from different backgrounds, better-connect with their values and interests, and give back to the communities that have shaped me.

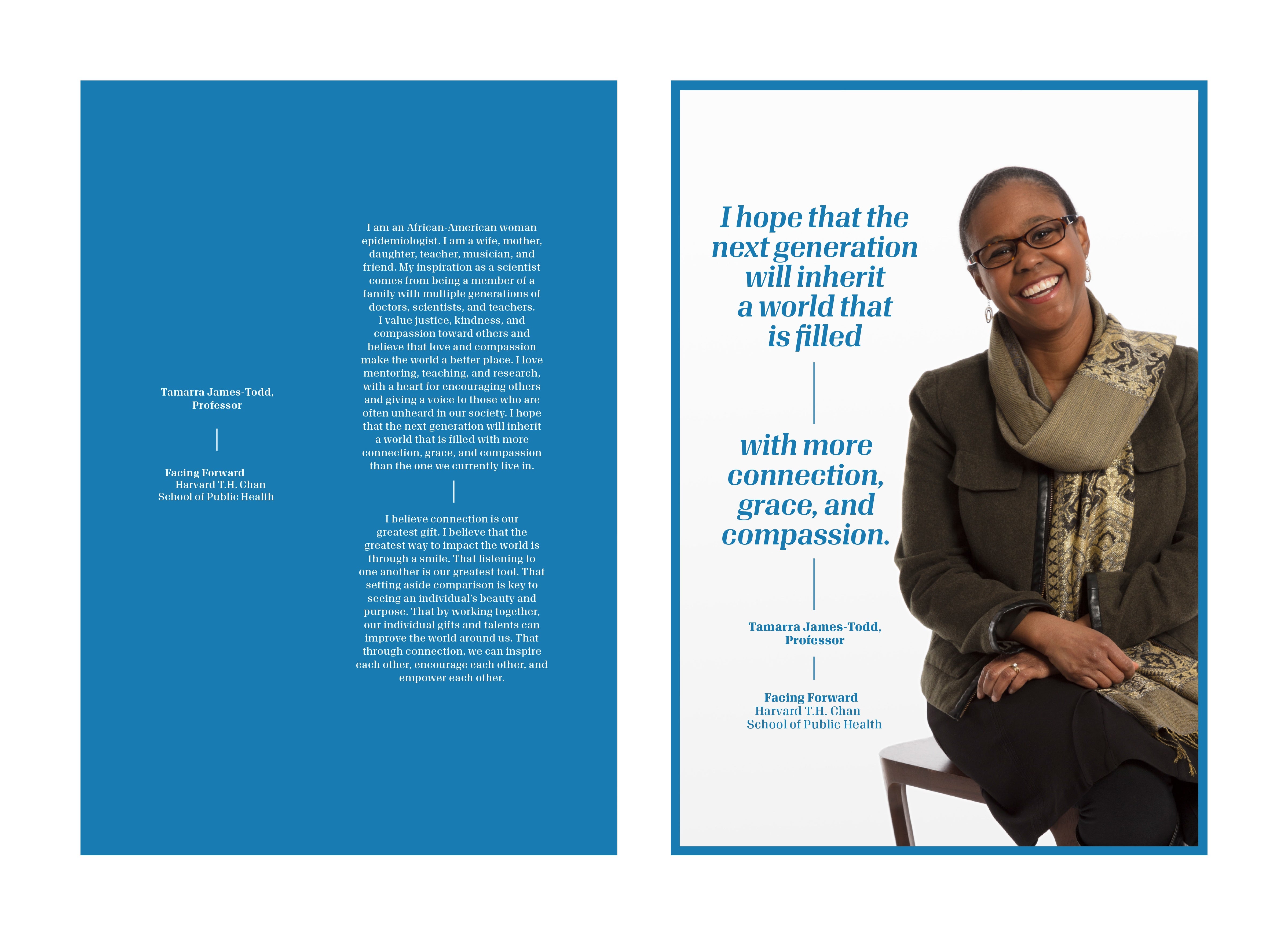

Tamarra James-Todd

I am an African-American woman epidemiologist. I am a wife, mother, daughter, teacher, musician, and friend. My inspiration as a scientist comes from being a member of a family with multiple generations of doctors, scientists, and teachers. I value justice, kindness, and compassion toward others and believe that love and compassion make the world a better place. I love mentoring, teaching, and research, with a heart for encouraging others and giving a voice to those who are often unheard in our society. I hope that the next generation will inherit a world that is filled with more connection, grace, and compassion than the one we currently live in. I believe connection is our greatest gift. I believe that the greatest way to impact the world is through a smile. That listening to one another is our greatest tool. That setting aside comparison is key to seeing an individual’s beauty and purpose. That by working together, our individual gifts and talents can improve the world around us. That through connection, we can inspire each other, encourage each other, and empower each other.

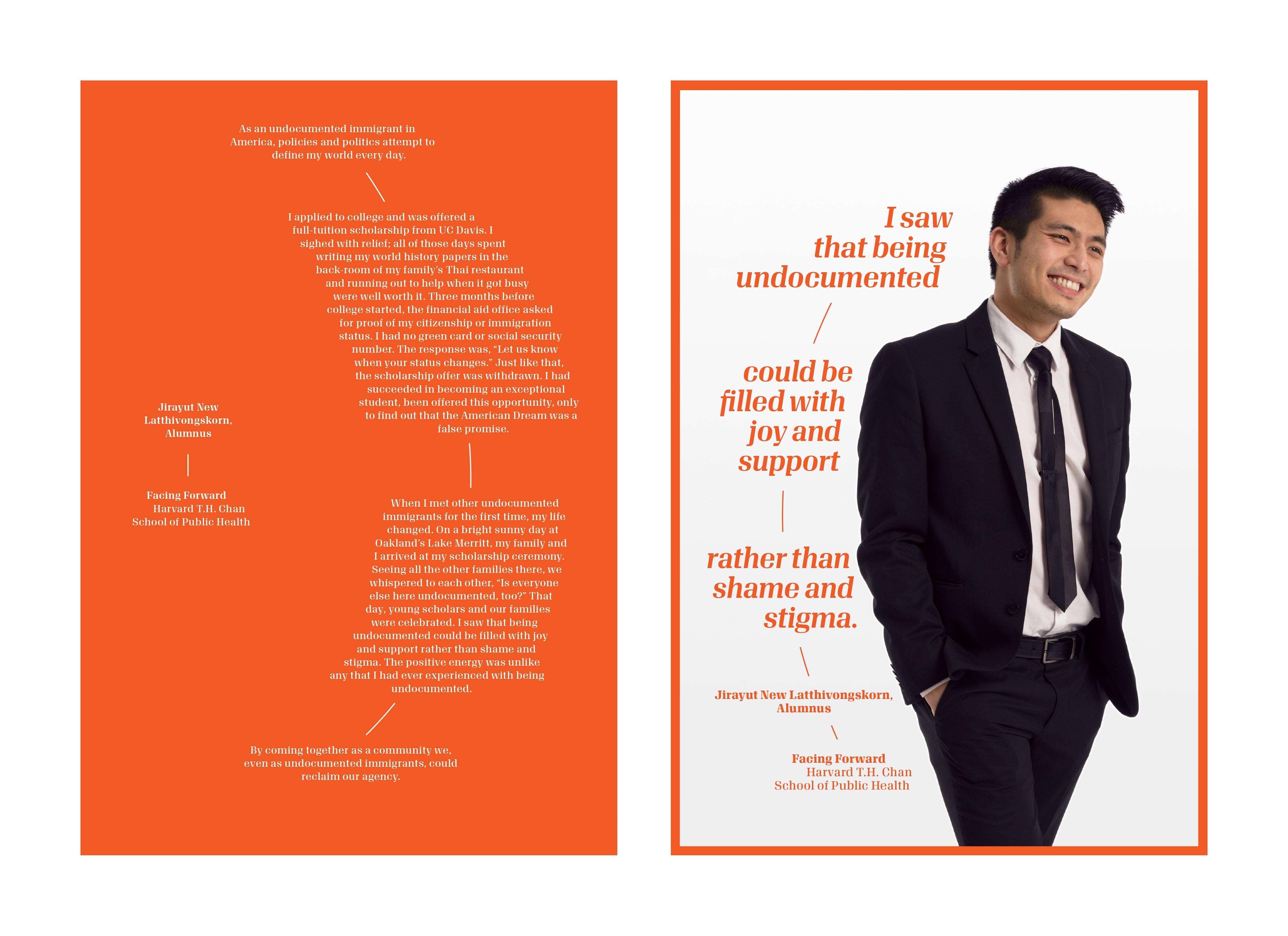

Jirayut New Latthivongskorn

As an undocumented immigrant in America, policies and politics attempt to define my world every day.

I applied to college and was offered a full-tuition scholarship from UC Davis. I sighed with relief; all of those days spent writing my world history papers in the back-room of my family’s Thai restaurant and running out to help when it got busy were well worth it. Three months before college started, the financial aid office asked for proof of my citizenship or immigration status. I had no green card or social security number. The response was, “Let us know when your status changes.” Just like that, the scholarship offer was withdrawn. I had succeeded in becoming an exceptional student, been offered this opportunity, only to find out that the American Dream was a false promise.

When I met other undocumented immigrants for the first time, my life changed. On a bright sunny day at Oakland’s Lake Merritt, my family and I arrived at my scholarship ceremony. Seeing all the other families there, we whispered to each other, “Is everyone else here undocumented, too?” That day, young scholars and our families were celebrated. I saw that being undocumented could be filled with joy and support rather than shame and stigma. The positive energy was unlike any that I had ever experienced with being undocumented.

By coming together as a community we, even as undocumented immigrants, could reclaim our agency.

Adam Mastoon is a transmedia storyteller, author, and educator. His work utilizes the power of images and narratives to celebrate diversity, equity, and inclusion in communities nationwide. www.adammastoon.com