Erica Walker, SD ’17, biked around Boston to take the measure of a city’s noise and its effects on residents.

Hot coffee dripping. Steamed milk hissing. Muzak droning. Keyboards clacking. Patrons murmuring: Erica Walker’s soft voice was almost drowned out by the ambient noise in a Starbucks. It was an ironic touch, considering that Walker has spent the past five years intently tuned in to Boston’s cacophonous urban soundscape.

The 36-year-old researcher, who will receive her doctorate in environmental health next year from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, has pedaled nearly every inch of the city on a purple commuter bike—hauling a bulky sound monitor, a boom microphone, and a camera in her backpack—all in the service of plotting sound levels in 400 separate locations and collecting residents’ subjective responses to the aural onslaught.

Most people have approached her with curiosity and, on learning her mission, gratitude. A few, alarmed by the paraphernalia of her sonic surveillance, have reported her to the police.

It’s all in a day’s research for Walker, a former artist who was compelled to undertake the study after suffering her own noise nightmare. The children living in the apartment above hers “ran across the floor literally 24 hours a day, and it drove me crazy,” says the Mississippi native. Plagued with headaches and sleeplessness, she sent out an impromptu Craigslist survey asking about annoying footstep sounds and was flooded with responses. She began to suspect her auditory torment was not isolated.

SIGNATURE SOUNDS

SIGNATURE SOUNDS

Walker has discovered that each Boston neighborhood carries a unique acoustic signature. The dominant note of Dorchester, for example, is transportation. “You have planes, you have trains, you have automobiles,” Walker says. But Dorchester’s rich cultural diversity also lends evocative countermelodies

to the main theme. “Something I hadn’t planned on is people standing outside and yelling across the street to each other, or sitting on their porches talking really loud—that human element,” Walker laughs. She wonders: “If people are part of that cultural landscape, is it ‘noise’ or just ‘sound’?”

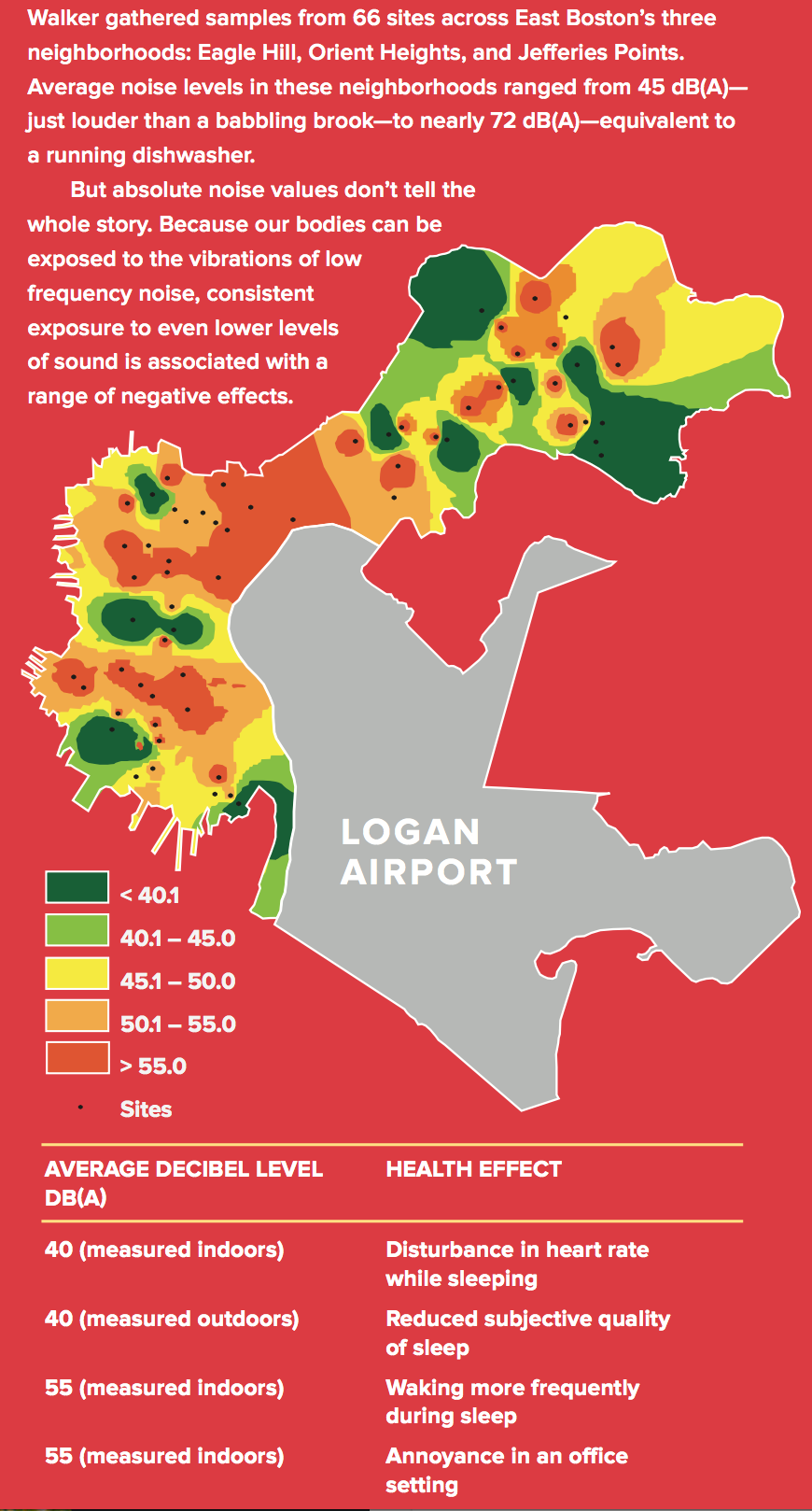

By contrast, East Boston, which abuts Logan International Airport, is perpetually assaulted by the din of low-flying jets. In a community survey that Walker created, one resident called the commotion “a regular horror.” Another lamented, “Everybody is walking around looking wrung out, some are getting nasty, kids are crying more, kids with behavioral issues are out of control. People don’t know what to do.”

THE MISMEASURE OF NOISE

Most formal surveys of sound gauge what are known as “A- weighted decibel levels,” or dB(A)—sounds that are perceptible by the human ear. Boston’s noise ordinance defines “unreasonable or excessive noise” as that in excess of 50 dB(A) between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m., or in excess of 70 dB(A) at other hours. To put this in context, normal human speech at about 3 feet apart takes place at between 55 and 65 dB(A).

Walker found that the city’s ordinance thresholds are routinely flouted. Boston’s two loudest enclaves—East Boston, with the roar of jet engines, and Savin Hill, awash in jangling nightclub noise from across Marina Bay—average 80 dB(A). Passing ambulances clock in at 105 decibels. Construction site jackhammers reach 112. Even those neighborly conversations between porches can hit 85 decibels.

And these numbers don’t tell the whole story. Walker

is also measuring a type of low-frequency noise called “infrasound.” Although vibrations at this level are not picked up by the ear, our bodies still register them. “Infrasound is totally inaudible; we don’t hear it, we just feel it, such as when a bus passes by or a plane takes off,” Walker says.

In nature, low-frequency vibrations take the form of thunder, earthquakes, volcanoes, or nearby herds of wild animals. Such vibrations signal approaching danger—a clue to the toll they may take on mental and physical health in modern urban environments. “Maybe our body is processing these vibrations and we don’t know it,” Walker suggests. Making matters worse, infrasound is not only highly prevalent in cities but also persistent, hard to mitigate, and it travels long distances.

What Walker wants to know is: Are these low-frequency noises, which are rife in urban environments but not included in standard A-weighted decibel measurements, exacting a hidden public health toll?

NOISE AND HEALTH

NOISE AND HEALTH

To find out, Walker, along with her adviser, Francine Laden, MS ’93, SD ’98, professor of environmental epidemiology, will map audible and infrasound noise levels across Boston’s neighborhoods, using color gradients to denote areas of higher or lower average sound intensity. Walker will also catalog residents’ perceptions of noise levels, using the Greater Boston Neighborhood Noise Survey, an instrument she developed that is being translated into Spanish, Simple Chinese, Vietnamese, and Haitian Creole. The survey, Walkers says, “will put a human face on community noise.” Eventually, Walker will correlate soundscape metrics with data from established health studies conducted in Boston to learn if any type of noise is linked to cardiovascular and mental health outcomes.

Walker’s research takes place in the midst of a heated discussion about airplane noise—much of it low-frequency—in Greater Boston. In December 2015, U.S. Rep. Stephen Lynch, who lives in South Boston, hosted a forum with Federal Aviation Administration officials, during which residents from across the region furiously recounted tales of babies constantly woken, rising asthma rates in families living beneath flight paths, and spouses sleeping in basements to escape the racket of Logan’s traffic. According to Lynch’s office, aircraft noise complaints in Greater Boston have worsened since the installation of a new GPS-based navigation system that directs planes on the most efficient route.

Francesca Dominici, professor of biostatistics at Harvard Chan, co-authored a 2013 study published in the British Medical Journal, which found that elderly individuals living on the noisiest flight paths near airports have a 3.5 percent increase in cardiovascular hospitalization for every 10-decibel increase in airport-related noise. She also found a strong association between noise exposure and cardiovascular hospitalizations in ZIP codes with noise exposures greater than 55 decibels.

For her part, Walker will be posting Boston sound maps and updates on her project’s progress at www.noiseandthecity.org. She has been biking Boston’s clamorous streets long enough to know that the most anguished complaints are about airplanes, construction, booming bass tones from car stereos, and barking dogs.

She can sympathize. “People don’t have a place to voice their noise issues,” Walker says. “They’re just kind of stuck here, suffering. And the city has no idea what’s bothering them.”

Jennifer Smith is a staff writer for the Dorchester Reporter.