[ Fall 2011 ]

In Kenya’s arid Wajir district, across the border from Somalia, attending school is not a given. Though some children learn to read while sitting on the floor in crowded classrooms or gathered on the dusty red ground under a tree, others must stay home to help tend the livestock so vital to the nomadic community’s precarious existence.

Osman Abdullahi was one of the lucky ones, and he hopes to someday return his community’s investment by taking on one of the district’s worst scourges: tuberculosis.

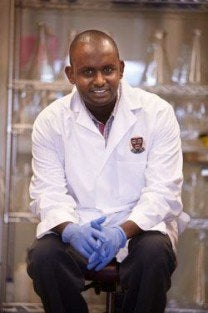

For Abdullahi, now a molecular epidemiologist and a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard School of Public Health, the past year at HSPH has been a key stop on a very personal quest. He has delved into what makes the TB bacterium tick—particularly how its strains vary in their transmission, ability to cause disease, and susceptibility to antibiotics, as well as what happens in the body of a person infected with more than one strain. After completing his fellowship at an HSPH-affiliated research facility in South Africa, Abdullahi plans to return to Kenya next year to open his own tuberculosis lab.

“One day, she was gone.”

Kenya has the 13th-highest tuberculosis burden in the world and the fifth highest in Africa, according to the World Health Organization. TB rates are especially high in Wajir and other pastoralist districts in the country’s North Eastern Province. Worldwide, TB kills more adults than any other infection, claiming about 2 million lives annually, a figure that includes more than 450,000 people also infected with HIV. Each year also sees 10 million new cases of the infection.

Growing up, Abdullahi, now 33, recalls that TB was part of the fabric of daily life. “My neighbor was very thin and coughing all the time. One day, she was gone. My parents told me she had been quarantined.” After spending six months receiving treatment in an isolated hut outside town, the neighbor returned fat and healthy, Abdullahi says. But a case left untreated could quickly lead to disaster in this communal society.

Today, tuberculosis research remains rare in Kenya. Infrastructure constraints, misinformation, and a potent stigma surround the disease. Two years ago, Abdullahi was shocked by the response to a patient who was admitted to the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret, Kenya, for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB).

“Everyone was scared—the hospital, the media, and even the poor man’s relatives. No one knew how to handle this patient,” Abdullahi says. “He was isolated in a building and people suggested that we burn it down to rid ourselves of XDR-TB. But as an epidemiologist, I knew that this case was only the tip of the iceberg.”

A Quest to Learn

After getting his first taste of epidemiology as an undergraduate, Abdullahi longed to understand why the infection was so prevalent in his largely nomadic community—and to do something about it. “I was desperate for training,” he says. With no formal programs in epidemiology offered in Kenya, he seized opportunities where he could—a research assistant position with the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kenya and later a PhD scholarship to The Open University in London—even though they required a focus on pneumococcus, a common bacterial cause of pneumonia, ear and sinus infections, sepsis, and meningitis.

While collaborating with HSPH Professor of Epidemiology Marc Lipsitch during his PhD program, Abudullahi was encouraged to come to the School to finally study TB. He received financial support from the Christopher W. Walker, Esq. Fund for Tuberculosis Research and Information Sharing at Harvard School of Public Health. He quickly impressed his adviser, Sarah Fortune, assistant professor of immunology and infectious diseases, with his vision and his drive to learn a complicated new set of skills.

Working at The KwaZulu-Natal Research Institute for Tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa this year, Abdullahi will dig deeper into the molecular biology of drug-resistant TB. And he’ll help forge connections between HSPH researchers, including Fortune, and African researchers that he hopes to tap into when he returns to Kenya to open his own lab.

Abdullahi aims to leverage Kenya’s widespread use of mobile phones and online social networks to calculate a more reliable estimate of the country’s TB burden. He also intends to establish collaborations with international colleagues in labs that are equipped to conduct whole-genome sequencing and other sophisticated studies.

Armed with this new scientific knowledge, Abdullahi hopes to create interventions based on the unique needs of Kenyan pastoralist communities like Wajir, where families are large, communal gatherings are frequent, and ventilation is poor—ideal conditions to spread TB. His own deep roots in the area may be key to making a difference, he says.

“People are skeptical of ideas from foreigners. But if they see you as local, they say, ‘You are talking a language we understand’ and take you seriously. I will be able to have an influence because I understand the dynamics.” And with small victories at the local level, the spreading tide of the disease may begin to turn. “I don’t think TB will be eliminated for a long time, because we are dealing with a disease that dwells in the way people live,” Abdullahi says. “But I believe that with research and education, we will be able to reduce it.”

Amy Roeder is assistant editor of the Review.