January 1992. The scene in Mogadishu was as close as it comes to hell on earth. As Somalia’s civil war gathered force, “the fighting was a combination of direct slaughter and indiscriminate firing of very heavy weapons on a city built of sandy concrete,” recalled Jennifer Leaning, director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights, who traveled to the war zone on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights. Figuratively and literally, “the city crumbled. People were trapped, killed, mutilated, and brought to hospitals that were completely unequipped to handle complex casualties.”

For the past 20 years, that experience has continued to inform Leaning’s work in ways that are crucial to the center’s mission. “What I saw in Mogadishu underscored my understanding that half measures to support a population in need are fraught with peril. It focused me on the importance of medical ethics and competence and the training of humanitarians. The people who were there were heroic. I honor them. But they knew what they were doing was not enough. They knew they were not at the top of their game.”

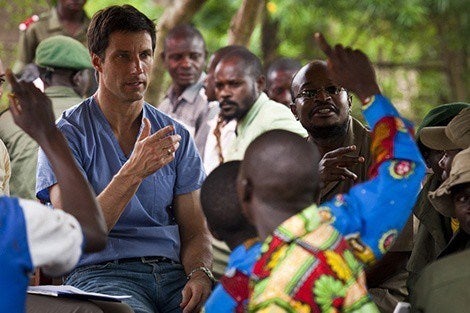

Training humanitarian workers to be effective in such disasters has since become a key goal of both the FXB Center and the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI), which Leaning co-founded in 2005 with Michael VanRooyen, who now directs HHI. “How do you train people to work in humanitarian environments that are fluid and difficult?” says VanRooyen. “We need to recognize humanitarian assistance as a unique and specialized discipline. Students must know not only about humanitarian principles and the basic provision of services, but also about finance, personnel, diplomacy, culture, and very practical matters of security. They also need to be creative and to lead. The toughest challenge is teaching leadership.”