[ Fall 2011 ]

The National Preparedness Leadership Initiative teaches seasoned professionals how to handle unprecedented disasters.

At the World Trade Center on 9/11, the New York Fire Department set up a command center at the bottom of World Trade Center One. The supervisors had a vertical view of the disaster—and based on that information, they sent firefighters rushing into the building to help with evacuation.

By contrast, the New York police dispatched a helicopter to hover near where the planes hit—a horizontal view. From that perspective, it was clear that girders were red hot and about to melt, and that the building would soon collapse. With that information, the NYPD ordered all police to evacuate. That day, 23 New York police died and more than 320 New York firefighters lost their lives.

This tragic anecdote frames a key lesson at a unique joint program run by Harvard School of Public Health and the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS): the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative, or NPLI. The initiative blends academic theory with practical insights from the field.

In the case of the 9/11 attacks, the lesson is known as the “cone in the cube” quandary. Observed through a hole on the side of a box (or building), the cone looks like a triangle. Observed through a hole in the top, it looks like a circle. The point is that different responders with different expertise and missions may perceive emergencies differently—but need to glean each other’s perspectives to smoothly choreograph their efforts.

The Five Dimensions of Meta-LeadershipThe Person:

|

Bad Leadership is a Public Health Risk

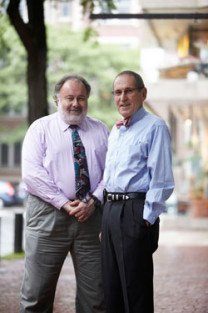

Co-directed by Leonard Marcus, lecturer on public health practice at HSPH, and David Gergen, director of the Center for Public Leadership at HKS, NPLI is grounded in the idea that U.S. leaders have much to learn about managing large-scale disasters, both natural and man-made. One of the singular aspects of NPLI is that its faculty have observed leadership close-up during such signal events as the Deepwater Horizon spill, Hurricane Katrina, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and the H1N1 pandemic response.

As public health risks grow ever more complex—with terrorist threats, emerging infections, globalization of the food supply, and climate change and natural disasters—leaders need different skills than they did in the past. Some 350 individuals have taken NPLI’s intensive on-campus executive education course, and more than 4,000 have participated in shorter city-level summits. Armed with new skills and a broader perspective, graduates return to high-impact jobs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), state and local health departments, the Departments of Defense and of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Authority, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and health ministries of other nations.

The mainstay of the program is an on-campus course, during which students learn the principles of “meta-leadership.” Marcus and NPLI faculty member Barry Dorn, associate director of HSPH’s Program for Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, coined the term after analyzing the actions of leaders in unprecedented emergency situations.

“In NPLI, we don’t teach management, we don’t teach budgeting, we don’t teach supervision in the classic sense,” explains Marcus. “We teach leadership—because in a crisis, bad leadership is a public health risk.”

Meta-Leadership

The “meta” in “meta-leadership” means reaching above and beyond one’s scope of authority to forge ties across disciplines and bureaucracies. Once the concept was captured in a phrase, says Marcus, more questions arose: “How do you describe it? How do you teach it? And how do you ensure that someone can actually do it?” He and Dorn distilled five teachable dimensions of meta-leadership.

NPLI’s hands-on approach to researching crisis leadership yields valuable insights, which are immediately incorporated into the meta-leadership training curriculum. For example, “In preparedness, time is your ally. In response, time is your enemy. The longer it takes you to respond and get it right, the more likely you are to fail,” says Marcus. “A quick assessment that is close to the mark and moves the process forward is better than a slow, though more accurate, response that comes too late to make a difference.”

Confident, Calm, Focused

The benefits of NPLI are quickly apparent in a crisis, says Dorn. “These leaders are confident, calm, focused. They are clear about the overall mission. And people working with a meta-leader know what they have to do to help accomplish the mission.”

In March 2009, for example, a novel strain of influenza, dubbed H1N1, surfaced in Mexico and spread to the United States. By late April, the outbreak had hopscotched across the globe. It was what public health officials had long feared: the first flu pandemic in 40 years—and in this case, the same subtype of the virus behind the devastating 1918 flu.

As the epidemic unfolded, Richard Besser, acting director of the CDC, found himself remembering lessons he had learned at NPLI. In fact, recalls Besser—now a visiting fellow at HSPH, as well as chief health and medical editor at ABC News—it was the first time in his career that he felt he was drawing on all of his strengths in the face of a public health crisis.

During the H1N1 response, “I deliberately tried to make sure I was hitting all of the leadership domains within the NPLI meta-leadership approach,” says Besser. “You have to look at leading yourself, leading the event, leading across silos, leading up, and leading down.”

The most compelling proof of the program’s success is the fact that many NPLI alumni occupy positions of influence at federal, state, and local health agencies. “When H1N1 hit,” says Marcus, “most of the senior CDC leaders had been through NPLI.”

“In choosing students for NPLI, we don’t pick the appointed leaders—the Secretary or Assistant Secretary,” adds Dorn. “We pick the highest government service employee in that organization, because they’re the ones who are going to persist and eventually lead.”

Madeline Drexler is editor of the Review.