News

Stay connected with Harvard Chan School

The latest public health news delivered right to your inbox.

From Our Students

All News

Public health communications take hit in federal agency layoffs

Widespread layoffs this week by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services included employees at federal health agencies responsible for communicating with the public, a move that is likely to harm public health, according to experts.

Faculty elected fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Xihong Lin and K. Vish Viswanath have been recognized for scientific excellence and service.

Lead, mercury levels higher in firefighters who fought L.A. urban blazes

Firefighters who fought urban blazes during the January wildfires in Los Angeles County had significantly higher levels of mercury and lead in their blood than firefighters who tackled past blazes in less-populated areas, according to preliminary findings from a consortium of researchers conducting a long-term study of the fires’ health impacts.

Exploring strategies for improving nutrition and planetary health

The Thich Nhat Hanh Center for Mindfulness in Public Health’s symposium focused on the power of social connectivity for making change.

Public health and the arts: A conversation with A.R.T.’s Diane Paulus

Diane Paulus, the Tony Award-winning Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director of the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) at Harvard University, discussed the power of theater to illuminate critical public health…

Mental health services in greater demand amid political upheaval

Stress due to the current U.S. political climate is leading more individuals in Massachusetts to seek mental health help, according to experts.

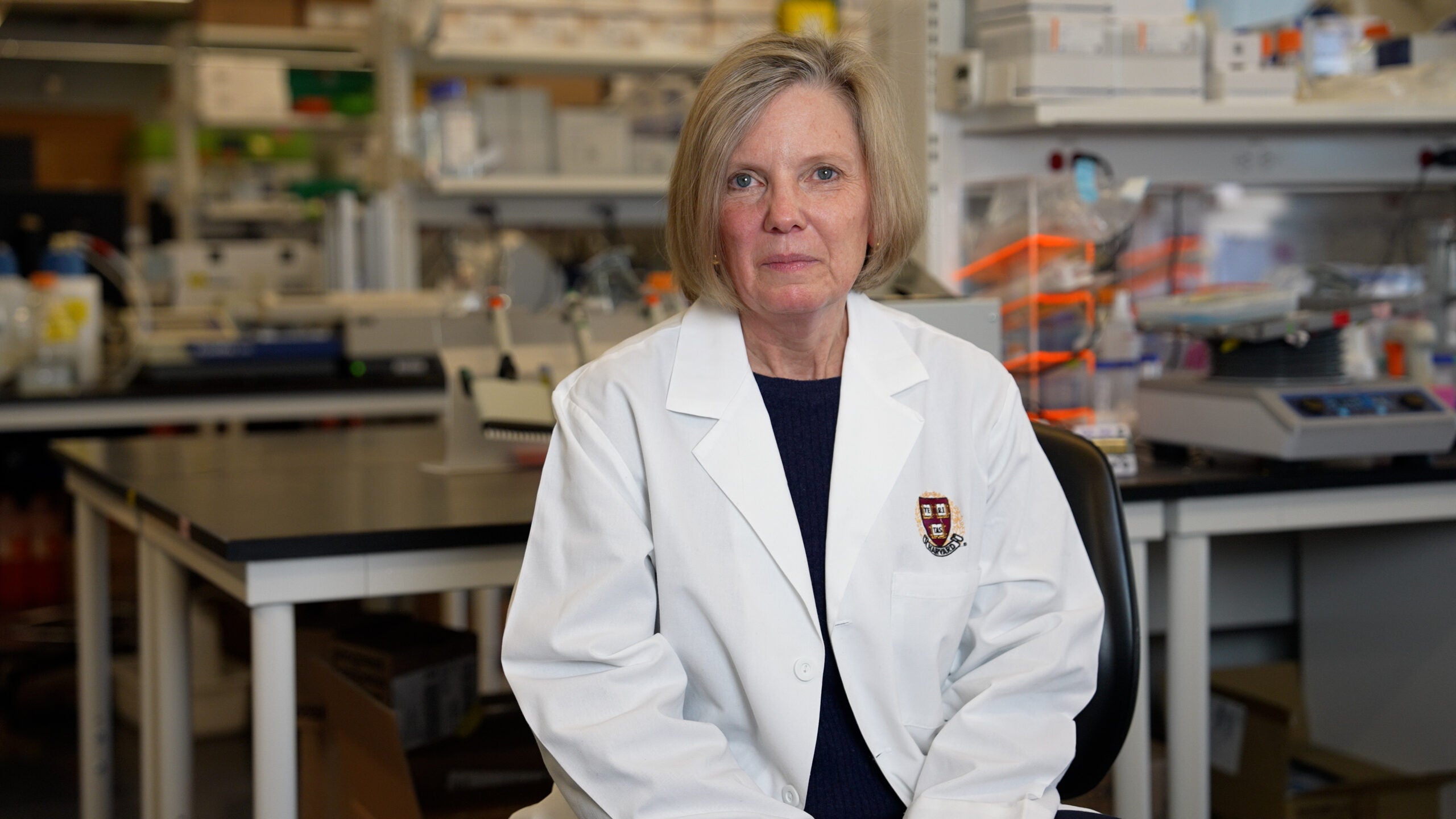

The importance of funding infectious disease research

Sarah Fortune, chair of the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at Harvard Chan School, says that funding research is vital to scientific advancement.

Removing artificial additives from the U.S. food supply

For decades, a regulatory loophole in the U.S. has allowed food companies to use ingredients—including artificial dyes—that have not been reviewed for safety. But there’s a move afoot to close that loophole, which could help protect public health, according to experts.

Exploring physician anti-nuclear war activism

Countway Library exhibit Prescriptions for Peace highlights role of health care professionals in anti-nuke movement.

Dean Andrea Baccarelli on driving change amid deep challenges

In this Harvard Gazette Q&A, Baccarelli discusses his vision for expanding the School’s impact while navigating a rapidly shifting landscape for federally funded research.