Ensuring safe, accessible drinking water in schools is a national health priority. The objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of school water quality, availability, and education-related practices, and determine whether there were differences in those practices by school characteristics.

Ensuring safe, accessible drinking water in schools is a national health priority. The objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of school water quality, availability, and education-related practices, and determine whether there were differences in those practices by school characteristics.

In 2017–2018, researchers analyzed data from the 2014 School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS), a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of U.S. elementary, middle, and high schools. The analyses examined differences in water-related practices by school characteristics. Response rates for the 3 questionnaires used in this analysis ranged from 69%–94%.

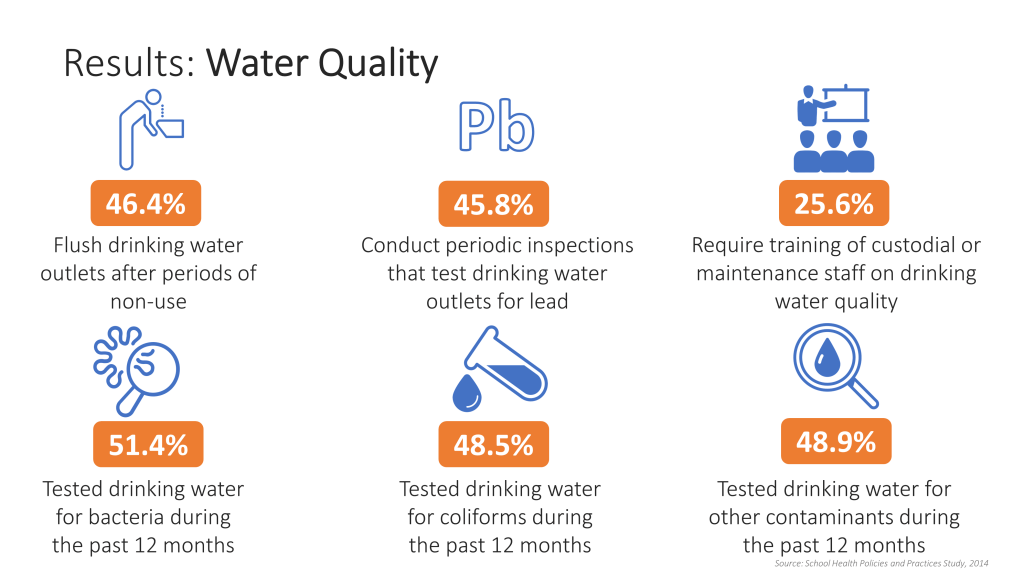

The researchers found that less than half of schools flush drinking water outlets after periods of non-use (46.4%), conduct periodic inspections that test drinking water outlets for lead (45.8%), and require staff training on drinking water quality (25.6%). Additionally, they found that most schools teach the importance of water consumption (81.1%) and offer free drinking water in the cafeteria (88.3%).

Some water-related school practices differed by school characteristics though no consistent patterns of associations by school characteristics emerged. In U.S. schools, some water quality-related practices are limited, but water availability and education-related practices are more common. SHPPS data suggest many schools would benefit from support to implement best practices related to school-drinking water. For example, such support could include:

-

- Establishing critical funding mechanisms to ensure that schools are able to conduct water quality testing and remediate issues when they arise, and

- Providing guidance for developing required training of custodial or maintenance staff on drinking water quality.

This project was conducted in partnership with researchers the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Principal Investigator: Angie Cradock, ScD, MPE

Funder: Healthy Eating Research (HER), a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF Grant #74374)

Contact: Angie Cradock, ScD, MPE

Peer-Reviewed Publication

- Cradock AL, Everett Jones S, Merlo C. Examining differences in the implementation of school water-quality practices and water-access policies by school demographic characteristics. Prev Med Rep. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.10082. Epub 2019 Feb 8.