By Nkasiobu F Wodu and Madhawa Palihapitiya

Is atrocities prevention possible through early warning and early action (EWEA)? Do early warning systems work? Or is it a search for unicorns (Austin, 2004). The skepticism about EWEA systems arises when early warnings do not translate into early actions (Matveeva, 2006). Third-generation early warning systems were developed, primarily in the “global south” (now called the “majority world”), which linked early warning with early action by community groups (Palihapitiya, 2018). Field-based EWEA systems may offer a solution for dealing with low-profile conflicts upstream before they escalate into mass atrocities as these mechanisms are more reliable early response mechanisms, particularly when state, bilateral, and multilateral agencies fail to respond to atrocities repeatedly. In many instances of catastrophe, the earliest sources of relief come from the endangered population themselves (Barrs, 2006). Early warning systems of this nature were developed with the realization that communities facing threats may ensure human security through their organic processes (Meier, 2007).

One Nigerian organization, the Foundation for Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta (PIND), provides an example of community-based response in Nigeria’s Niger Delta region. Through a combination of spatial maps and technology, leveraging community expertise and ownership, PIND’s Early Warning and Early Response system has contributed immensely to violent prevention and reduction in a region troubled by violent conflict.

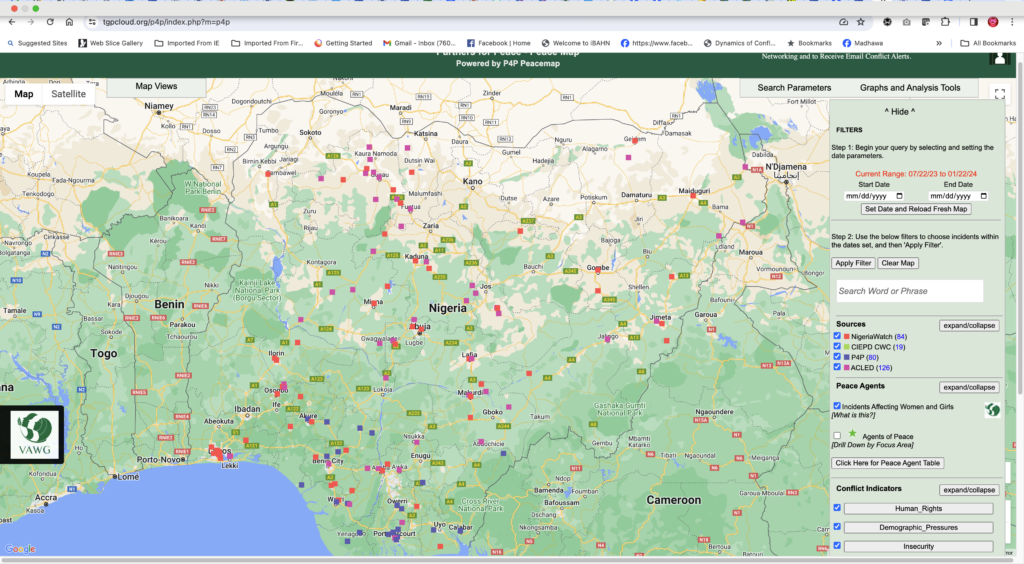

There are three major components to PIND’s integrated early warning and response system: the technology component, the community component, and the response system. Each of these components is interdependent and related to each other. The technology called the Peace Map consists of a geospatial map that collates data from multiple organizations, collecting data points on conflict and violence. The Peace Map is a database of conflict incidents from multiple sources across Nigeria, allowing users to triangulate and validate data. It contains hotspots and enables the user to compare the intensity of violent conflict over time within specific geographic locations.

The community itself comprises another significant component of the system, which includes thousands of individuals under the Partners for Peace Network (P4P) platform. P4P was established in 2012 as a network of peacebuilders comprising traditional rulers, community leaders, teachers, local politicians, and young people across the Niger Delta region. Reports from thousands of P4P volunteers are integrated into the peace map. Essentially, P4P reports contribute to data on the peace map among data from other sources such as the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) and Nigeria Watch. However, P4P does not only contribute to the data; P4P members are also community responders mobilized to prevent or mitigate violent conflict (PIND, 2020).

The third component is the response. PIND’s technical research team analyzes data from the peace map using spatial methods. These analyses are presented as conflict bulletins and weekly, monthly, and quarterly conflict reports. These reports contain specific information about the conflict, such as key actors, drivers, hotspots, etc. They are used as a tool for further analysis on the ground by P4P responders to validate and contextualize the data using their local understanding of the actors and drivers. They then use this in-depth information to formulate strategies for response. PIND refers to this strategy as an operational response. Another more strategic response involves engaging with influential stakeholders to prevent violence. For example, in a conflict between two rival communities, a strategic response could be using a highly placed traditional rulers, clerics, or government officials to bring the stakeholders together to a settlement.

In this way, PIND has adapted to the challenges of community-based response by playing to the strengths of community responders while, at the same time, ensuring that it provides resources such as data, funds, and capacity building to them to improve their ability to respond to conflict situations. Of course, this system still has challenges – response time may be too slow, sociopolitical factors could defeat the political will to resolve some intractable conflict, and integrating response across multiple locations is still tricky. However, an integrated system organized around spatial data shows that even some of the tenuous challenges to community response can be surmounted and adapted to meet local needs.

Nkasi Wodu is a Senior Fellow of the Aspen Institute, A Global Governance Scholar at the University of Massachusetts, Boston and former Program Manager of PIND’s Peacebuilding Program.

Madhawa “Mads” Palihapitiya is an early warning expert, lecturer and the Associate Director of the statutory state dispute resolution office in Massachusetts.