The “Analysis of Provider Payment Reform on Advancing China’s Health” (APPROACH) project evaluated a social experiment that modified the provider payment system at county-level hospitals. In collaboration with the Government of Guizhou–one of the poorest provinces in China with a large rural population–we launched a social experiment in 28 counties of Guizhou in from 2016 to 2018. Another 28 counties served as control counties, which allowed us to evaluate data from hospital information systems, New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) claims records, and two hospital surveys.

Background

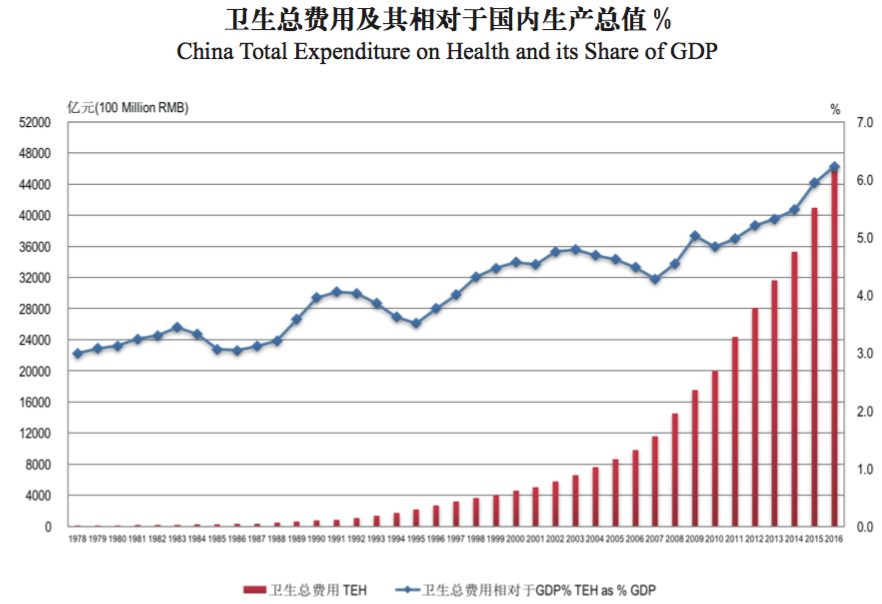

Health care expenditure in China has been increasing rapidly, both in real terms and as a percentage of GDP, as is shown in the figure below. While various health care schemes have covered over 95 percent of the population by the end of 2011, the financial protection they offer are insufficient, leaving many households vulnerable to catastrophic health expenditure.

One root cause of the increase in expenditure is misaligned incentives faced by health care providers. They are paid by fee-for-service (FFS) according to a fee schedule that overpays for drugs and high-tech diagnostic tests and underpays for basic services, such as consultations. As a result, both overprovision (of profitable drugs and tests) and underprovision (of unprofitable basic services) are common, leading to cost escalation and inappropriate treatments.

The Chinese government has acknowledged this problem and placed great importance on provider payment reform in the latest Five Year Plan. Specifically, the plan calls for a shift from FFS to prospective provider payment methods (PPM), such as global budget, capitation and case-based payments.

In collaboration with the Government of Guizhou (one of the poorest province with a large rural population in western China), we launched a social experiment in Guizhou in 2016. Our intervention is targeted at the PPM for inpatient services of the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS). It changes the PPM from FFS to a mixed payment method combining a disease-based global budget and pay-for-quality (hereafter GB+P4Q) for county hospitals. Under this method, county hospitals receive a prospective budget based on the size of the enrolled population in NCMS at the beginning of the year, with 30 percent of the budget withheld and disbursed based on performance assessment biannually. The capitation rate is calculated to cover county hospital expenditure and a portion of out-of-county expenditure based on spending over the last three years.

Policy Intervention

Study Design

Project Partners

Research Products

- Lin X, Jian W, Yip W, Pan J. Perceived Competition and Process of Care in Rural China. Risk Management Healthcare Policy. 2020;13:1161-1173. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S258812 Although there is much debate about the effect of hospital competition on healthcare quality, its impact on the process of care remains unclear. This study aimed to determine whether hospital competition improves the process of care in rural China. The county hospital questionnaire survey data and the randomly sampled medical records of bacterial pneumonia patients in 2015 in rural area of Guizhou, China, were used in this study. Our results suggested that the likelihood of receiving antibiotic treatment and first antibiotic treatment within 6 hours after admission was significantly higher in the hospitals perceiving higher competition pressure. However, no significant relationship was found between perceived competition and oxygenation assessment for patients with bacterial pneumonia. This study revealed the role of perceived competition in improving the process of care under the fee-for-service payment system and provided empirical evidence to support the pro-competition policies in China’s new round of national healthcare reform.