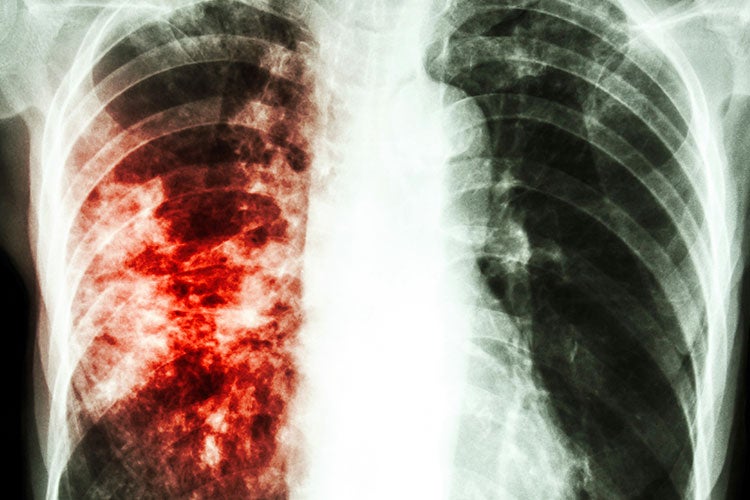

In January 2016, the small town of Marion, Alabama made national headlines for the tuberculosis outbreak that has gripped the residents for the last few years. In the town of fewer than 3,600 people, 29 had been diagnosed with active tuberculosis (TB) – three of whom have died – six people in other cities in Alabama were diagnosed with cases of active TB linked to the Marion outbreak, and more than 150 other residents have been infected but are not yet showing symptoms. The incidence rate is currently 100 times higher than the state’s, and officials expect the number of infected residents to increase as more people are tested.

The incidence rate of TB in Marion, 253 cases per 100,000 people, is not only 100 times higher than the state’s rate, but also worse than many developing countries’ including Afghanistan, India, and South Sudan. How does this happen in the United States?

The Poorest County in Alabama

Perry County, of which Marion is the county seat, is the poorest county in Alabama, which is the fourth poorest state in the country by median household income; in Perry County, 26 percent of residents live below the poverty line and the annual per-capita income is $13,000. The unemployment rate is twice the state average.

Poverty has affected how testing and treatment of TB have been handled in Marion. Many residents were wary of medical workers who first tried to test for TB (see below). Widespread testing only began when the local health department was able to use grant money to pay $20 to anyone who gets a blood test, another $20 to return for the result, $20 for coming to get a chest X-ray if necessary, and $100 if a patient with TB completes treatment. While this plan is controversial, it has been successful. In the three weeks that the department offered a financial incentive, over 2,000 people in Perry County were tested. As of the end of January, officials were still offering testing, but not payments.

Alabama also has some of the most restrictive Medicaid eligibility in the country, and because the governor of Alabama rejected the federal government’s Medicaid expansion, childless adults are not eligible for coverage. As a whole, 11 percent of that state’s residents are uninsured, the 15th highest percentage of uninsured residents in the country. In Perry County alone, 20 percent of residents do not have health insurance.

Globally, more than 80% of TB occurs in high-burden countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. The Marion outbreak illustrates the challenges that this pathogen still poses even in “resource-rich” settings like the US. It illustrates the impact of poverty on healthcare delivery and epidemic control.

This lack of access to health care is one of the reasons that TB has spread through Marion. Not only is there a lack of health insurance coverage, but, like in many other poor rural areas, even residents who have health insurance lack options. While Marion has two family medicine clinics and a public health department that provides some basic medical services, Perry County has a severe shortage of primary care physicians. In the county, there are approximately 5,000 residents for every primary care physician, compared to approximately 1,600 for the state as a whole.

TB is uncommon, but far from unheard of in the United States; outbreaks are usually checked by prompt diagnosis and treatment of those affected. But in places where residents can’t see a doctor because they either lack insurance or because there simply isn’t a doctor to see them, TB can spread quickly and turn deadly if someone is infected.

A Legacy of Suspicion

Another complicating factor of the outbreak in Marion is the legacy of the Tuskegee experiments, which deeply entrenched a suspicion of medical workers, particularly those associated with the government. Tuskegee, two hours from Marion, was the site of one of the most notorious medical experiments in United States history, where federal researchers studied the progression of untreated syphilis in 600 black male sharecroppers. Working under the guise of providing free medical care, the researchers never informed the men of their diagnosis and did not offer penicillin or any other cure. The research lasted for 40 years.

In Marion, where 63 percent of residents are black, suspicion of both medical professional and government health workers has been passed through generations, according to reports from the town. While there were positive TB tests in Marion in 2014 and two deaths in 2015, public health officials were unable to trace associates of those infected and by most accounts, were ignored when they tried to get blood samples from others in the town. There were even reports of residents throwing bottles at health care workers who had set up a testing fair. This lack of testing and surveillance allowed TB to spread throughout the community to unprecedented levels.

Even this incidence rate of TB has not turned government health workers into trusted sources or allies. According to a report in the New York Times, many residents say they believe that the government should have acted faster to quarantine the disease before it became an outbreak, while others believe the whole thing has been blown out of proportion.

When diseases impact particular sub-populations, the potential for blame and stigma increases while reducing rational health-seeking behavior. Tuskegee is but one example from our past that continues to impact the public health interventions for many diseases.

The legacy of Tuskegee and other medical experiments exist not just in Marion, but in black communities throughout the country. While Tuskegee is one of the best-known studies of this sort, there are many other federally funded studies that took advantage of black patients. Multiple studies have shown that trust is now the biggest factor in keeping black people from clinical trials, leading to potential dangerous gaps in research on health issues in black populations. In addition, this legacy means that there is not a culture of care-seeking behavior in many black communities, so the spread of TB was not uncovered until it was too late.

“Outbreak and epidemics, particularly with new or emerging pathogens, often evoke fear in the affected communities,” says Phyllis Kanki, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Tuskegee is but one example from our past that continues to impact the public health interventions for many diseases. Stigma and distrust of the healthcare system are responses that have hampered efforts to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS, for example.”

Rates of TB in black and other minority populations in the United States are over five times higher than the rate for white populations. While so far Marion has been unique in this level of outbreak, already high TB rates and suspicion of the medical community is a potentially dangerous mix for the spread of the disease.

A Small Community

Marion is a small town, and like in many small towns, residents report a fear of being stigmatized by others in the community. This fear helped the TB outbreak spread, according to authorities.

In a small community, where everyone knows everyone, you might not want people knowing exactly what you’re doing or whom you are doing it with. According to Pam Barrett, the state official leading the response, in a New York Times article, “the phrase that every single case uses is ‘I don’t want nobody knowing my business…If you’re doing maybe some things that you don’t want other people to know about, or doing some things you’re ashamed of, you don’t want people in your business, and you’re not going to tell me.”

Despite assurances that any information given will remain confidential, this fear of being stigmatized is a powerful deterrent from talking to the workers who came to help stem the outbreak, especially when combined with the aforementioned suspicion of outsiders generally and health care workers in particular. When health care workers cannot track the contacts of people with TB, they cannot track the potential spread of disease, and thus have a much harder time containing it. And not only are people diagnosed with TB reluctant to disclose their contacts, but potentially infected residents may not seek care to avoid being associated with the disease or people who have it.

“When diseases impact particular sub-populations, the potential for blame and stigma increases while reducing rational health-seeking behavior,” says Kanki.

Outbreak and epidemics, particularly with new or emerging pathogens, often evoke fear in the affected communities. Stigma and distrust of the healthcare system are responses that have hampered efforts to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.

Could It Happen Anywhere?

In some ways, Marion and Perry County as a whole are unique. It is the poorest county in one of the poorest states, is severely lacking in health care access, and happens to be situated very close to the site of one of the most infamous experiments in medical history. And yet, Marion is in most ways not very different than other towns with similar poverty levels and racial makeups.

In this case, a confluence of factors lead to a TB outbreak spreading nearly uncontrollably, but this sort of outbreak is very rare in the U.S. In fact, the national number of new infections decreased by more than 2 percent between 2013 and 2014, when the first cases in Marion appeared. Another Marion-like outbreak is possible, but preventable with proper surveillance and treatment, which involves gaining the trust of residents and providing adequate preventive care. These are not always easy tasks, but they are necessary to prevent the spread of communicable disease.

“The Marion outbreak illustrates the challenges that this pathogen still poses even in ‘resource-rich’ settings like the US,” says Kanki. “It illustrates the impact of poverty on healthcare delivery and epidemic control.”