On a sweltering July afternoon, Monica Bharel, MPH ’12, peers into a rail-road underpass in Worcester, Massachusetts. Bharel, 46, became commissioner of the state’s Department of Public Health (DPH) in February 2015. She stands next to Martha Akstin, community relations director of AIDS Project Worcester (APW), which is located a block away. APW is supported by the department’s HIV Prevention and Treatment funding, and it’s Bharel’s final stop in a day of hospital and clinic visits— field tours that tether her public health vision to on-the-ground reality. Rather than evaluating programs, launching new initiatives, or making speeches, Bharel has spent most of the day listening and learning.

Akstin motions into the shadowy underpass, beyond a scattered wall of tires and trash, where the silhouettes of tattered recliners and a couch peek above the debris. “That’s where the active users go,” she says. Bharel nods. Her formal attire suits her earlier meetings with physicians and hospital executives better than standing in parched weeds near the railroad tracks. But this encounter is no less important to Bharel, the top public health professional in a state where overdoses kill nearly five people per day, on average, and where one in five men and nearly one in three women with HIV become infected by sharing needles. To help prevent future infection, APW outreach workers frequently collect discarded heroin needles from this underpass, or the users themselves bring dirty needles to APW to exchange for clean ones. As a physician who spent decades working with Boston’s homeless population, Bharel knows places like this well. And her swift professional ascendancy—from front-line clinic doctor caring for some of the state’s most marginalized residents to leader of its sprawling public health bureaucracy—vaults Massachusetts into the spotlight as a proving ground for tackling some of the most thorny issues in the field, including drug addiction and health disparities.

DISPARATE HEALTH RANKINGS

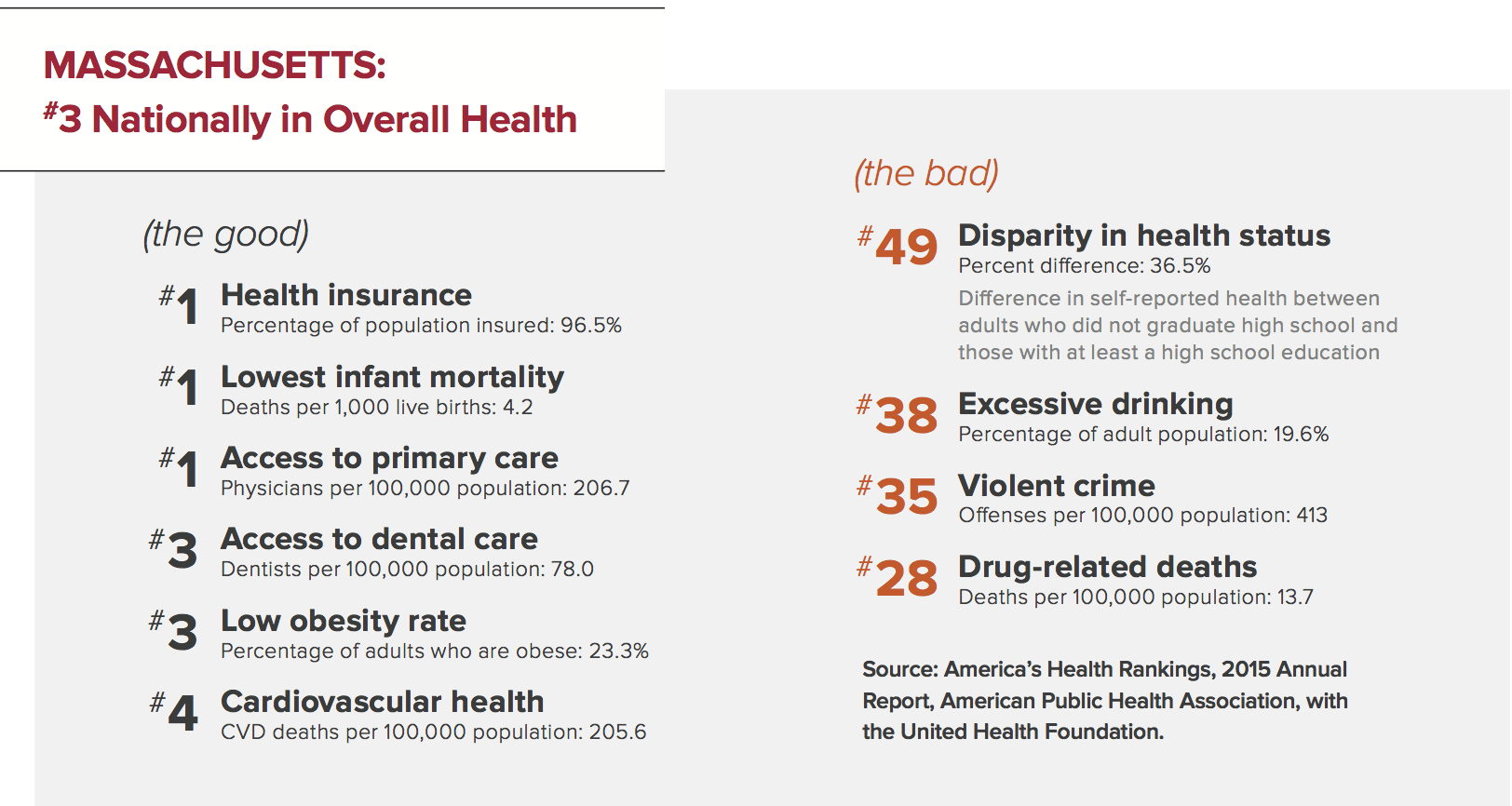

In a 2015 report, the American Public Health Association ranked Massachusetts as the third healthiest state (below Hawaii and Vermont), thanks to its low levels of obesity, smoking, and cardiovascular disease. The same report, however, ranked the state 49th in health disparities. “The reality is that too many people live in an unhealthier Massachusetts,” Bharel said to a joint hearing of the Massachusetts House and Senate Ways and Means Committees in February 2016.

Bharel knows well the stories behind the statistics on persistent public health challenges. Those stories have taught her that more medical care alone will never be a solution. Good health is also rooted in a safe place to sleep, a job to pay the gas bill, a home free of toxins and violence, a caring community of neighbors, and myriad other factors known as health’s “social determinants.”

Bharel now oversees a billion-dollar budget, the state laboratory, four hospitals, and a staff of about 3,500. Her department’s bailiwick includes everything from food safety to medical marijuana. In the midst of all this, Bharel keeps her focus on making health care more responsive to people’s unique life circumstances. By linking high-quality medical care with a broad array of social services—all informed by fine-grained, up-to-date data—she hopes to foster a holistic and equitable vision of public health.

A BIGGER DEFINITION OF HEALTH

Bharel, whose parents emigrated from New Delhi, India, grew up in New York City and Long Island. Her father is a doctor, and his example sparked her early desire to help people heal. She spent many childhood summers in New Delhi and was stunned by the abject poverty of people living on the city’s streets.

After high school, Bharel volunteered with a team from a New Delhi hospital that drove into the slums to offer basic medical care, such as malaria screenings and child vaccinations. Later, as both an undergraduate and a medical student at Boston University (BU), she volunteered with Anna Bissonnette, a nurse and professor at BU’s medical school who founded Hearth Inc., a nonprofit providing health care and social services to homeless elderly people.

It was in medical school that Bharel started working with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), which cares for about 12,500 homeless men, women, and children annually. She continued the collaboration with BHCHP during her residency at Boston City Hospital, now Boston Medical Center.

In 2003, BHCHP founder and president Jim O’Connell hired Bharel to be medical director of the Barbara McInnis House, where homeless people receive short-term medical and recuperative services. Five years later, she became the organization’s chief medical officer.

When Bharel talks about her patients from these years, she tells stories of lives that became unmoored. For instance, there was the woman with severe abdominal pain. In repeated visits to the emergency room, CAT scans had revealed nothing. Finally, the woman opened up to Bharel about her history of domestic abuse and how she constantly felt in danger. Bharel found her a bed in a women’s shelter and connected her to a primary care team, easing the fear and stress that triggered her stomach troubles.

“She didn’t need another expensive scan. She needed somebody to listen to her,” says Bharel. She started asking all her patients, “What does good health mean to you?”

Their answers rarely mentioned medicine or the formal health care system. Instead, they’d say, “I need a home. I need somewhere other than the shelter where I can rest and heal. I want to see my children and my family,” Bharel recalls. “My patients taught me a bigger definition of health.”

Massachusetts Department of Public Health Commissioner Monica Bharel, MPH ’12 (center), meets with staff from the interprofessional Center for Experimental Learning and Simulation at UMass Medical School. The Center’s executive director, Michele P. Pugnaire, is third from left.

CLINICIAN TO POLICYMAKER

“Monica is a fabulous doctor, an astute clinician who is fiercely devoted to her patients individually,” O’Connell said. “At the same time, she always had this remarkable ability to see the bigger picture.”

A growing frustration with that bigger picture made Bharel eager to get more involved in public health policy. In 2012, she earned her master’s through the Mongan Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“I kept seeing the same patients again and again with the same problems, because we were unable to address the social determinants impacting their overall health,” says Bharel. “Entering the world of public health was about going upstream to find solutions. The School helped me make sense of the obstacles I was seeing in caring for my patients and how it was all connected to our policies as a state.”

The fellowship’s director, Joan Reede, Harvard Medical School’s dean for diversity and community partnership, insisted that students take an economics course, Bharel recalls, “because when you sit at the table, you’ll need to understand finances if you want to make the changes that matter.”

In her ethics course, Bharel reread the classic treatise A Theory of Justice, in which the philosopher John Rawls proposes that we choose our principles of justice from behind a “veil of ignorance”—as if knowing nothing about individuals’ race, gender, social status, intelligence, or abilities.

Bharel credits Robert Blendon, the Richard L. Menschel Professor of Public Health and professor of health policy and political analysis, for “infusing the reality of politics” into her ideal of health justice. “Working within the system to make change, as opposed to advocating from the outside, it’s really important to know where the levers are,” she says. “Everybody has an agenda, and you have to have negotiation skills.”

She quickly adds, “I know exactly what I stand for, and what the right thing to do is. The compromise isn’t about your principles; it’s about can you get everything you want right now.”

During her fellowship, Bharel had the chance to spend a day shadowing the state’s commissioner of public health, concluding it was “the coolest job ever.” A couple of years later, Marylou Sudders, whom Governor-elect Charlie Baker had appointed Secretary of Health and Human Services, asked Bharel to come by her office. Sudders had been commissioner for the Department of Mental Health from 1996 to 2003. She knew Bharel professionally, because she was a board member of the Pine Street Inn, Boston’s largest homeless shelter, and she shared Bharel’s concerns about health disparities.

Sudders didn’t immediately tell Bharel why she had asked her to meet. But as the women discussed a range of issues, it didn’t take long for Sudders to broach the job offer. “I think I did catch her a bit breathless,” Sudders recalls. But she knew Bharel was her top choice. “She’s a boots-on-the-ground physician, trained in management, who has spent a career helping the neediest,” says Sudders. “She’s never satisfied with the status quo.”

For her part, Bharel saw the offer as an opportunity to apply what she knew about the barriers to good health to, as she puts it, “a place where I have people around me and access to information and data to influence policy design.” Her initial worries—leaving a job that she loved and the potential impact on her family (she and her husband, Sushrut Waikar, MPH ’06, a clinical scientist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, have two young children)—were soon allayed.

“Monica has moved on to a bigger stage, with bigger challenges. But it’s a stage where she belongs,” says BHCHP’s O’Connell. “There are no easy decisions, but I’m thrilled that somebody with a lightning-quick mind, who understands what it means to be poor and left out, will have a voice in those decisions.”

TACKLING THE OPIOID CRISIS

In a crowded conference room at her first Worcester stop, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Bharel watches closed-circuit television of a medical student in a nearby exam room. The student is interviewing a “standardized patient,” an actor playing a role—in this case, a middle-aged African-American man in a sling who winces as he complains that his prescribed painkillers aren’t strong enough and the pain is keeping him out of work.

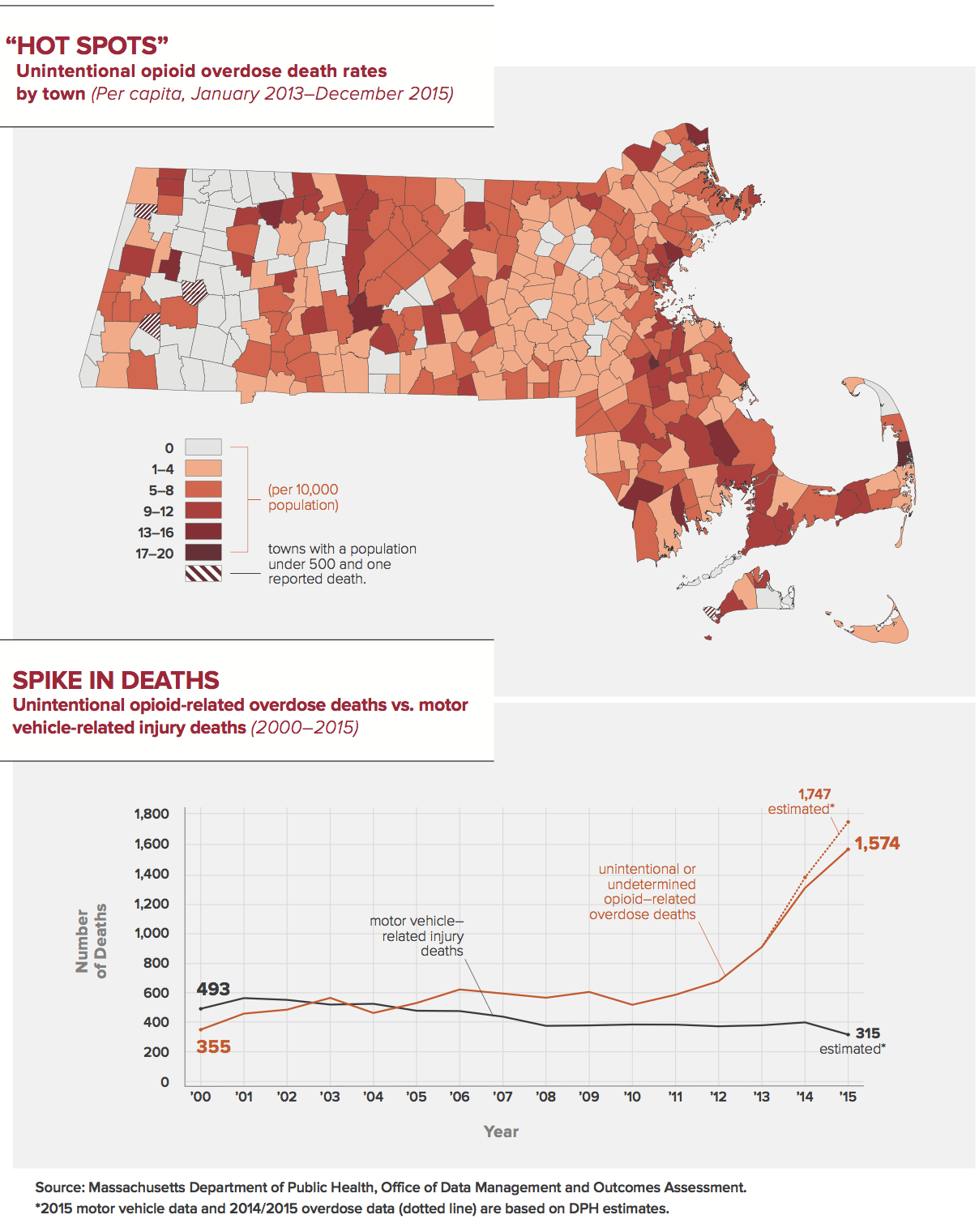

It’s one of several simulations in a new curriculum for prescribing painkillers, a leading cause of opioid addictions that often transition to the cheaper high of heroin. Massachusetts is among the hardest hit states in a nation-wide opioid epidemic. In 2014, the most recent year of data compiled by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 12 states had an overdose death rate higher than that of Massachusetts.

At the behest of a task force created by Governor Baker, Bharel and about four dozen medical experts established 10 “core competencies” for prescribing opioids—such as judging a patient’s risk of addiction and offering nonopioid pain management advice. The state’s four medical schools will build required courses around these competencies, and UMass is the first to do so.

Medical students in the course also hear from a panel of people in recovery from substance-use disorders and from those whose loved ones suffer from addiction. A few of these individuals are at the table with Bharel. They speak about the stigma of addiction and how it can keep people from getting help.

“Sometimes, a doctor will see my history and it’s like they just want to get me out the door as soon as possible,” says Meghan Giacomuzzi. Prescribed painkillers led both her and her brother into heroin addiction. She’s in recovery now, but her brother died of an overdose in 2012, at the age of 27. “We’re not bad people,” she adds, “we’re sick people.”

Finally, Bharel addresses the room. “I’ve heard stories like this many times before, and it chokes me up every time,” she says, her voice cracking. “It takes tremendous courage to speak about this. It’s part of the healing process for you, but it’s teaching for all of us. This is a medical disease, and it has to be treated like one.”

CRAFTING A NATIONAL MODEL FOR TREATMENT

With Bharel leading the charge, the state’s comprehensive attack on the opioid crisis has become a national model. “It is unacceptable that nearly five people are dying each day in Massachusetts from this,” she says. “Prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery supports must continue to be a priority. For too long, this epidemic was not seen as the public health issue that it is. This is also an opportunity for us to focus on improving integration of behavioral health with primary care in Massachusetts.”

The state’s multipronged approach is a first. In no other U.S. state do all teaching institutions, professional societies, and state government join together to form voluntary core competencies in opioid prescription. Bharel believes this collaborative model could be applied to other problems as well—and proves that academic institutions and medical schools, far from occupying ivory towers, can respond rapidly to urgent public health challenges.

The STEP (Substance use, Treatment, Education, and Prevention) law signed by Governor Baker in March 2016 was one of the most far-reaching of its kind. As Bharel explains, “We have developed an award-winning, nationally recognized public health campaign to fight addiction and the stigma that is associated with it. We have one of the most expansive uses of nasal naloxone [used to counteract the effects of opioids], and we have been innovators in expansion of buprenorphine [a partly synthetic opioid used to treat opioid addiction] treatment through neighborhood health centers. And we are seen as a leader in our use of data in public health response to the opioid crisis.” In October 2016, Bharel described the state’s groundbreaking program at the White House Frontiers Conference, which convenes innovative leaders in science, technology, and research.

ENDING INEFFICIENCIES: A MORAL IMPERATIVE

Later in her visit to UMass Memorial, Bharel is interviewed by a gaggle of newspaper and television reporters. A high-profile political job has been an adjustment for Bharel. In her previous position, interviews were always for positive stories about the good work of BHCHP. Now, there are administration policies to emphasize and defend. “I’ve learned more in the last 18 months than anytime since medical school,” Bharel says later.

Following several years of cuts, the state’s budget for public health (about half of the department’s funding is federal) jumped to $584.9 million in FY 2017 from the 2016 level of $533.3 million (a state budget de cit may trim that figure, however). While Bharel would welcome more money, she is focused on eliminating inefficiencies in her department’s services.

It’s not bean counting, Bharel says—it’s a moral imperative. She deems waste of limited health care resources “unconscionable.” She felt the same way as a doctor treating patients with chronic diseases that could have been prevented for a fraction of the cost, and seeing expensive treatments fail because they ignored the thorny realities of a patient’s life.

HOMING IN ON “HOT SPOTS”

Bharel has pushed for more comprehensive and faster data analysis at the state level to track the impact of public health programs and pinpoint or even predict public health “hot spots” for more targeted interventions. One example is the new online Massachusetts Prescription Awareness Tool, aka MassPAT, launched in the summer of 2016. Among its key goals: preventing opioid addiction.

Unlike the older prescription tracking system, MassPAT can be linked with a patient’s electronic medical records and includes prescriptions filled outside Massachusetts. The information is updated in real time and streamlined so doctors can see patients’ prescription histories in just a few clicks, saving precious minutes for busy physicians. “This is a huge improvement, giving prescribers critical information about their patients and letting us look for potential patterns of overprescribing,” Bharel says. In a related effort, since 2015 the department has released data on opioid overdose deaths quarterly, rather than every two years.

The data initiatives are too new to have spawned major, statewide policy changes, but they have uncovered areas for future focus. For instance, the opioid epidemic is often believed to mainly affect young, white men—but the data show that Hispanics make up a disproportionate percent of overdose deaths, a fact that reinforces the need for multi-lingual outreach. Data also show that most opioid prescriptions are written for people over 55, suggesting that seniors need education about how to store and use their medications appropriately.

The intended audience for these new revelations isn’t just policy wonks on Beacon Hill. It’s the local officials, schools, and community groups that create and run many of the prevention, education, and intervention programs that Bharel’s department funds and supports.

“The nature of this crisis is changing so quickly that we wanted to make sure every city and town in the state has up-to-date information,” says Bharel. “Maybe there’s a town where they haven’t seen many opioid deaths, but now they’re starting to spike. People can target their own communities, have teachers and coaches talk to their students about the dangers of these drugs—interventions that are purely based on seeing the numbers.”

TEAMING UP WITH COMMUNITIES

In June 2016, DPH launched another data-driven initiative: the Massachusetts Environmental Health Tracking tool, an online profile of every community in the state. The tool answers queries about community-level health issues, such as asthma rates and heart attack hospitalizations, and environmental issues, such as air quality and infectious-disease rates. The hub for these and future data initiatives will be a new Office of Population Health, which should be up and running by the end of 2016.

Bharel has also pushed for more collaborative efforts, such as the goal of eliminating childhood lead poisoning in Massachusetts. Every child in the Commonwealth gets tested for lead before he or she turns 4. After several years of steep declines, the prevalence of elevated lead levels has plateaued since 2011, hovering at just under 0.4 percent of children.

To break the impasse, DPH drafted preliminary regulations in 2016 that would cut the blood-lead levels equated with lead poisoning from 25 micrograms to 10 micrograms per deciliter—meaning more children will qualify for state lead-exposure services (such as home deleading). Once again, finer-grained data will be available for making hot-spot maps of lead poisoning statewide. These maps have been overlaid with location-based data on household income, the age of the housing, local water tests, and other factors that could collectively explain a particular community’s unusually high or low levels of lead contamination.

“Our goal is to address the clear disparities we see in lead exposure and lead poisoning in our Commonwealth’s children,” says Bharel. “We know that there is no safe level of lead exposure, and that there is a clear relationship between early exposure to lead and a child’s future school performance, employment status, and other measures that will significantly impact a child’s health and ability to succeed.”

MEASURING PROGRESS

During the late afternoon drive back to Boston from Worcester, a colleague briefs Bharel on unfolding events—a new E. coli outbreak traced to beef from New Hampshire, beaches that must close because of high levels of bacteria. Bharel will go home for dinner with her family—something she makes a point of doing whenever possible—and then she’ll get back to work.

“When I leave the o ce at 6 or 6:30, my staff calls it my lunch break,” she jokes, “because after my kids go to bed, I’m back on for hours.”

She’ll field emails until about midnight while reading a packet of briefings for the next day, which she keeps in a red folder. She has another folder for weekends.

With each late night and every policy brief read between innings at a Little League game or on the drive to a weekend dinner party, Bharel is chipping away at the state’s biggest, most recalcitrant health challenges. She measures progress incrementally—by how much smoking rates, childhood obesity, the prevalence of chronic diseases in adults, and deaths from substance abuse have dropped.

One metric, however, is not incremental. When it comes to health disparities, Bharel declares flatly, “I want to eradicate them.” She believes that half the battle can be won by deploying data to eliminate waste and ensuring that health resources get to those who need them. “I’m not saying it’s a two-year journey and we’ll be done. But my goal for this department is to get us on that path. And I firmly believe we can get there.”

Chris Berdik is a Boston-based science journalist. Follow him on Twitter @chrisberdik. Photography by Kent Dayton.