SLAVERY’S LEGACY IN HEALTH

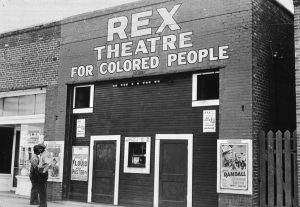

In studies of slaves and their descendants, many white physicians of the 18th through the early 20th centuries hypothesized and attempted to show that inherent racial weaknesses explained blacks’ poorer health, discounting the effects of enslavement and vast disparities in socioeconomic conditions. This research played a major role in constructing a narrative of race and scientific racism in the United States, the repercussions of which are still being felt in the lives and health of African-Americans. At a May symposium inspired by Harvard-wide efforts to uncover the University’s links to slavery, panelist Nancy Krieger, professor of social epidemiology, shared research documenting higher infant mortality and a higher likelihood of having a more lethal type of breast cancer (estrogen receptor negative) among African- Americans born in states with, as opposed to without, discriminatory Jim Crow laws. The event also marked the installation of the “Ghost Portraits” exhibition in Rosenau Atrium, featuring significant African-Americans and Native Americans in public health history.

DODGING ANTIBIOTICS: HOW THE TB BACTERIUM USES PROTEIN TO EVADE DRUGS

A single protein appears responsible for the ability of some tuberculosis-causing bacteria to evade antibiotics. Even when most of a patient’s overall population of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is wiped out by drugs, bacterial subgroups sometimes persist—a reason why treatment can be lengthy. To understand this variability, Eric Rubin, the Irene Heinz Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, and colleagues used a fluorescent dye to track differences in individual Mtb cells as they grew and divided. The scientists found that Mtb cells lacking a protein called LamA formed less diverse bacterial populations with more uniform susceptibility to antibiotics. According to Rubin, the findings suggest that adding a drug that blocks LamA to antibiotic regimens could speed up treatment.

SWEET NEWS FOR CHOCOLATE LOVERS

Eating a serving of chocolate with high cocoa content a few times a week may lower the risk of being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation—a common and dangerous type of irregular heartbeat—according to a new study by Harvard Chan scientists. Previous studies have suggested that cocoa and cocoa-containing foods confer cardiovascular benefits, perhaps because they are high in flavonols, a compound that may promote healthy blood vessel function. In the study, which looked at health data from 55,502 women and men, lead author Elizabeth Mostofsky, instructor in the Department of Epidemiology, and colleagues found that those who ate two to six servings of chocolate per week had the most benefit, lowering their risk of atrial fibrillation by 20 percent compared with infrequent chocolate eaters.

A GENETIC LINK TO PTSD?

A large new study provides the first evidence that genetic influences play a role in the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after trauma. The report finds that genetic risk for PTSD is strongest among women, particularly those of European ancestry, for whom 29 percent of the risk for developing PTSD is influenced by genetic factors. The study bolsters previous findings of shared genetic risk between PTSD and other mental disorders such as schizophrenia. Senior author Karestan Koenen, professor of psychiatric epidemiology at the School and head of the Global Neuropsychiatric Genomics Initiative of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at Broad Institute, and colleagues looked at genomic data from more than 20,000 people participating in 11 multiethnic studies around the world. PTSD may be one of the most preventable psychiatric disorders, according to the researchers, who hope that gleaning its genetic basis will help clinicians target interventions more effectively.

PRESCRIBING PATTERNS LINKED TO OPIOID USE

Emergency room patients treated by physicians who prescribe opioids more frequently than other physicians are at greater risk for long-term opioid use—even after a single prescription—than those who see less-frequent prescribers, according to the findings of a study in the New England Journal of Medicine led by Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management. Patients who received care from frequent opioid prescribers were three times as likely to receive a prescription for opioids as patients seen by infrequent prescribers in the same hospital. And individuals treated by the most-frequent prescribers were 30 percent more likely to become long-term opioid users—defined as receiving six months’ worth of pills in the 12 months following the initial encounter.

BANKING ON THE MICROBIOME

Scientists are poised to understand the many ways in which the microbiome—the trillions of microbial organisms that live on and inside our bodies—influences human health. To help boost this new field of research, the Harvard Chan School is creating an integrated hardware and software system to collect, use, and analyze microbiome-based specimens. The Biobank for Microbiome Research in Massachusetts (BIOM-Mass), a collaboration with Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, received a $4.9 million grant in May from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center. Led by a team of Harvard Chan faculty—including Eric Rimm, professor of epidemiology and of nutrition; Wendy Garrett, professor of immunology and infectious diseases; and Curtis Huttenhower, associate professor of computational biology and bioinformatics—BIOM-Mass will create the world’s most comprehensive human microbiome specimen collection, drawing on samples from more than 25,000 participants in the School’s long-running cohort studies. Researchers will mine this data for new insights into the complex interactions among the human microbiome, health, and disease.

AIR POLLUTION PROVES DEADLY FOR SENIORS

A study of 60 million Americans—about 97 percent of people age 65 and older in the U.S.—shows that long-term exposure to airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone increases the risk of premature death, even when that exposure is at levels below the National Ambient Air Quality Standards established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Researchers found that men, blacks, and low-income people were most at risk from PM2.5 exposure, with blacks experiencing mortality risks three times higher than the national average. The researchers also found that small reductions to PM2.5 and ozone standards could save thousands of lives. The study was published in June in the New England Journal of Medicine and was led by Francesca Dominici, professor of biostatistics at the Harvard Chan School and co-director of the Harvard Data Science Initiative.

THE PARADOX OF LABOR MANAGEMENT

The way certain hospital labor and delivery units are managed may put healthy women at greater risk for cesarean deliveries and hemorrhage. Researcher Neel Shah and colleagues found that women receiving care at hospitals with a culture of reducing risk factors before they arise were more likely to have a cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, blood transfusion, and prolonged hospital stay. Shah is an obstetrician and Harvard Chan School researcher who leads the Delivery Decisions Initiative at Ariadne Labs, a joint center of the School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The study’s counterintuitive findings, he says, may indicate that managers at these hospitals are focused on achieving different goals—such as neonatal outcomes or financial performance—which are not always aligned with maternal well-being.

EAT BETTER, LIVE LONGER

People who improve the quality of their diets over time, eating more whole grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and fish and consuming fewer red and processed meats and sugary beverages, may significantly reduce their risk of premature death. Harvard Chan researchers found that people whose scores on a healthy diet assessment improved over a 12-year period reduced their risk of death in the subsequent 12 years. Senior author Frank Hu, the Fredrick J. Stare Professor of Nutrition and Epidemiology and chair of the School’s Department of Nutrition, emphasized that there is no one-size-fits-all diet and that small changes over the long term can make a difference.

Another study led by Hu found that small increases in weight gain during early and middle adulthood may raise health risks later in life. Compared with people who kept their weight stable, those who gained a moderate amount of weight (5–22 pounds) before age 55 increased their risk of chronic diseases and premature death and decreased their likelihood of scoring well on an assessment of healthy aging. Higher weight gain was associated with greater risk of chronic diseases.