Since 2013, pediatrician Annie Sparrow has been traveling back and forth from New York to Syria’s border with Turkey, training Syrian medical personnel struggling to cope with the mounting casualties of their country’s brutal civil war.

In a small, drab conference room in a hotel in Gaziantep, Turkey, Annie Sparrow, MPH ’04, places her finger on a vein in the extended arm of a Syrian doctor. Here, she demonstrates to him and the other Syrian doctors crowded around the table, all watching closely—here is where you need to insert the needle for the intravenous drip. Next she shows them how to accomplish that procedure, which can be exceedingly tricky in a person who is severely wounded or starving—or, as frequently happens in Syria today, both. Sometimes, Sparrow says, the practice session “ends up spilling precious drops of Syrian blood.”

Sparrow has come to Gaziantep, a bustling city of 1.8 million near the Syrian border, to participate in a training workshop organized by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS). She and a group of doctors and nurses from SAMS will spend three days teaching their Syrian counterparts the intricacies of pediatric intensive care, malnutrition and starvation medicine, emergency interventions for acute trauma, and anything else the Syrians desperately need so they can save lives in the midst of their country’s nearly six-year-long nightmare. Called “the biggest humanitarian emergency of our era” by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in 2014, it has since become only more barbaric.

Home to 350,000 Syrian refugees—some living in camps but most crammed into city apartments—Gaziantep is a mere 61 miles north of Aleppo, once a jewel on the legendary Silk Road but now a place whose eastern half has been reduced to rubble. And although Gaziantep is in Turkey, ostensibly a safe haven for Sparrow’s work, it is not immune from violence. In August 2016, for example, a suicide bomber attacked a Kurdish wedding party, killing 57 people and injuring 66. Targeted assassinations also periodically erupt.

Sparrow’s trip to the Syria-Turkey border involves flying from JFK International Airport in New York to Istanbul, then taking another flight to Gaziantep. Sometimes her luggage is lost. And because of her frequent trips to the Syrian border and other areas in the Middle East, she has become a “person of interest” to national security personnel at JFK, routinely pulled out of the security line, interrogated, and comprehensively searched.

As uncomfortable as these journeys may be, her students—Syrian doctors, nurses, and midwives—take serious and calculated risks to attend the training sessions. They converge on the border from all over wartorn Syria, negotiating checkpoints or traversing hostile terrain. The border crossings—first the Syrian border, then the Turkish one—are difficult, dangerous, and often humiliating. Even if the Syrians have the required passports and provide fingerprints and a headshot, they often must wait hours to be allowed entry into Turkey. Some may stand outside for half a day, not permitted to take shelter in the border building, even being refused water. Many are denied entry. Others reluctantly give up and return home.

WARTIME IMPROVISATION

Since January 2014, Sparrow has made it her priority to participate in these trainings every three months—although the schedule is sometimes interrupted by events like the attempted coup in Turkey in July 2016. Once the group has gathered, her classes are often improvisational, because the ongoing conflict in Syria is exacting new and unfamiliar forms of pain and suffering. “I don’t always know what topics I will be teaching until I get there,” Sparrow says. “The Syrians are the ones who tell me what they need to learn.” Many of the Syrians now forced to serve as doctors were never fully qualified for the profession, often arriving with backgrounds as hospital technicians or medical students.

Sparrow, who tends to communicate urgently, in a torrent of words, is the only non-Arabic-speaking person in the room, relying on a translator to convey her material in Syrian Arabic. In the mornings, she and her SAMS colleagues cover topics such as infectious diseases, malnutrition, gastroenteritis, and intensive care. If she requires backup expertise, she may Skype friends in New York, where she now lives, and ask them to track down one of her old textbooks from Afghanistan or photograph recipes for malnourished kids and email them to her. Or she may contact colleagues in her native Australia via Whatsapp for advice about optimal treatment of congenital heart disease in resource-limited settings.

“We have to get quite inventive sometimes to simulate the procedures,” says Sparrow. “We’ll get a piece of sheep trachea at a butcher shop and then show the doctors how to puncture the trachea to create an emergency airway. I’ve used animal carcasses to help people learn to do lung punctures correctly.”

The afternoons bring practical workshops that can last well into the evening. The morning’s white-cloth-covered tables are converted into medical stations that the Syrian doctors will rotate through—to practice intubation, ventilation, vascular access, ultrasound screening, and other skills. “The room can be quite noisy, especially when the air compressor for the ventilator starts up,” Sparrow says. “Twice it has blown up in the middle of teaching. I’m the only one who jumps at the sudden loud sound, because, unlike the Syrians, I’m not used to bombs.”

Burnt vehicles litter the front of the severely damaged Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-backed al-Quds hospital. The building, in a rebel-held area of Aleppo, was hit by two airstrikes in April 2016. At least 55 people died and approximately 80 were injured. Those killed included a pediatrician and dentist who were among the few remaining medical specialists left in eastern Aleppo. The two were friends of Annie Sparrow and her SAMS colleagues.

She has become adept at acquiring critical supplies from the local environment. “We have to get quite inventive sometimes to simulate the procedures,” she notes. “We’ll get a piece of sheep trachea at a butcher shop and then show the doctors how to puncture the trachea to create an emergency airway. I’ve used animal carcasses to help people learn to do lung punctures correctly.” Sparrow also has worked with SAMS doctors as they employ real-time telemedicine—once guiding physicians in Syria resuscitating a baby born from the womb of a dead mother. Sparrow’s suitcases are filled with pocket-sized clinical guidelines and a raft of medical supplies, including battery-run blood pressure cuffs and pulse oximeters for when the Syrians face electrical power cuts, and special skin glue so they can close patients’ minor wounds, rather than taking time to stitch them up as bombing victims flood the makeshift hospitals.

With no spare room in her luggage, Sparrow’s clothes sometimes travel in her young son’s Toy Story backpack. Her appearance is the one area in which she does not improvise. She believes that even in wartime—perhaps especially in wartime—she must observe a respectful and civilized decorum. “It’s very important for me to look professional, feminine, and conservative,” she says, “because even if my Syrian colleagues struggle through storms and hike up and down hills to get to the trainings, they still do their best to turn out looking spotless. I need to do the same.” She favors colorful wool tunics that can survive being scrunched up in a bag and won’t show blood, urine, or other bodily fluids that might end up on them when she treats patients.

CONDEMNED BY HOPE

Sparrow admires the Syrian way of connecting in person. Although Syrians have had to become experts in digital communication and security to overcome the constraints and threats imposed by the government, they still prefer talking to texting. “One of my dearest doctor friends from Aleppo once told me that the human voice is the sound of life,” she says. And Gaziantep—one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world—brims with life and invites conversation. “We all feel it here—the Syrians, the Turks, even my son, who often comes with me,” Sparrow says.

Still, the war across the border often shatters that Old World civility. Last April after class, Sparrow shared a fine meal at an Armenian restaurant with three Syrian friends—two doctors and a pharmacist—and was persuaded to join one of the doctors for a family dinner at his apartment, followed by coffee and leisurely conversation. “So happy to hang out again. The kids always make me laugh after these long days,” she remarked in an audio diary. “Then we heard that al-Quds hospital had been hit and that one of our dear friends had been killed.” The friend was Wassim Maaz, the last pediatrician in eastern Aleppo.

Looking back at this and so many other deaths, Sparrow is philosophical, even through her tears. “Syrians—me too—we are condemned by hope,” she says. “As bad as it gets, you find some reason to hope in the midst of this darkness.”

WAKING UP TO INJUSTICE

Raised in Perth, Australia, Sparrow describes a childhood that often consisted of free-form weekends of hiking and living off the land (her mother could cook a five-course meal over a campfire). She always wanted to be a doctor—a sense of service inherited from her parents. “My mother was a huge force of good, in listening to people and making you do the right thing, and my dad was like that too. When bad things happened or I was feeling sorry for myself, my dad would say, ‘Come on. Do you live in a tree?’ and Mum would say, ‘Go find someone who’s more miserable than you are and help them. Just get on with it.’”

After earning her medical degree from the University of Western Australia, she practiced in Perth and then in London. A 1999 visit to her brother in Taliban-controlled northern Afghanistan, where he and his wife were conducting development work, was eye-opening: a world of deprivation she had never before encountered. She began to reconsider the high life she had been living in London.

Returning to Perth, she worked at a children’s hospital but, with her new perspective, also volunteered as a doctor at the Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre, a notoriously brutal detention camp housing refugees seeking asylum in Australia. Designed for 400 people, the camp—which operated from 1999 to 2003—at one point contained some 1,500 people, including hundreds of children. Accusations of human rights abuses were lodged by an array of organizations, and detainees registered their own protests by rioting, escaping, attempting suicide, staging hunger strikes, and even sewing their lips together in despair.

“That was when I had my epiphany and realized I couldn’t just work in a first-world hospital anymore, no matter how much I loved intensive care,” says Sparrow. “It’s good to realize these kinds of things. And once you realize it, you can’t go back. I decided to get into the world of humanitarian aid and refugee health and obtain an MPH.”

At the Harvard Chan School, she made lasting connections. One was with David Bloom, the Clarence James Gamble Professor of Economics and Demography in the Department of Global Health and Population, whom she still considers a key mentor. Bloom values his former student in turn. “Annie has an uncommon ability to see, with great clarity, both the forest and the trees—a result of her remarkable blend of clinical and scientific training and experience,” he says.

Sparrow also forged a deep friendship with Ellen Agler, MPH ’04, now CEO of the nonprofit END Fund, an organization working to end neglected tropical diseases. “Meeting Ellen was worth the whole price of admission,” Sparrow says. Her friend mirrors the sentiment. “Annie has such a huge heart and is one of the most clear, effective, intelligent, and passionate public health advocates and activists I have ever known,” Agler says. “She’s the embodiment of ‘fierce compassion,’ a true force for good in the world.” [Read Agler’s profile in the Fall 2015 issue of Harvard Public Health.]

It was also at Harvard that Sparrow first encountered her future husband, Kenneth Roth, executive director of the nonprofit Human Rights Watch. During an Iraq War debate at the Harvard Kennedy School moderated by Samantha Power, now the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Sparrow was impressed as he “systematically annihilated” the hawkish Canadian politician Michael Ignatieff. Too busy to stay to meet Roth after the debate, she recalls later confiding to Agler, “That’s a man I could marry.’”

Receiving a Harvard Human Rights Practice Fellowship upon graduation eventually led Sparrow to Human Rights Watch, where she became the organization’s first researcher with medical training. She credits that experience with helping shape her voice both as a doctor and as an advocate. She moved on, and after three years based in Nairobi, Kenya, working in several war-torn countries for the Emergency Response Team of Catholic Relief Services, she served another year as director of UNICEF’s malaria program in Somalia for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

A WAR ON HEALTH CARE

As of February 2016, the war in Syria—an outgrowth of a popular uprising in March 2011 that was brutally quashed by the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad—had claimed at least 470,000 lives, according to a report by the nonprofit Syrian Center for Policy Research. In 2016, the Assad regime and its ally, Russia, focused some of their most intense bombing on opposition-held areas, especially eastern Aleppo.

Sparrow has been sharply critical of the Syrian government’s flouting of international conventions on medical neutrality in war, according to which wounded and sick combatants have the right to receive aid and doctors, pharmacists, first responders, and relief workers have the right to provide it. “The Assad regime has come to view doctors as dangerous, their ability to heal rebel fighters and civilians in rebel-held areas a weapon against the government,” she wrote in 2013 in The New York Review of Books. “Over the past two and a half years, doctors, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists who provide treatment to civilians in contested areas have been arrested and detained; paramedics have been tortured and used as human shields, ambulances have been targeted by snipers and missiles; medical facilities have been destroyed; the pharmaceutical industry devastated.”

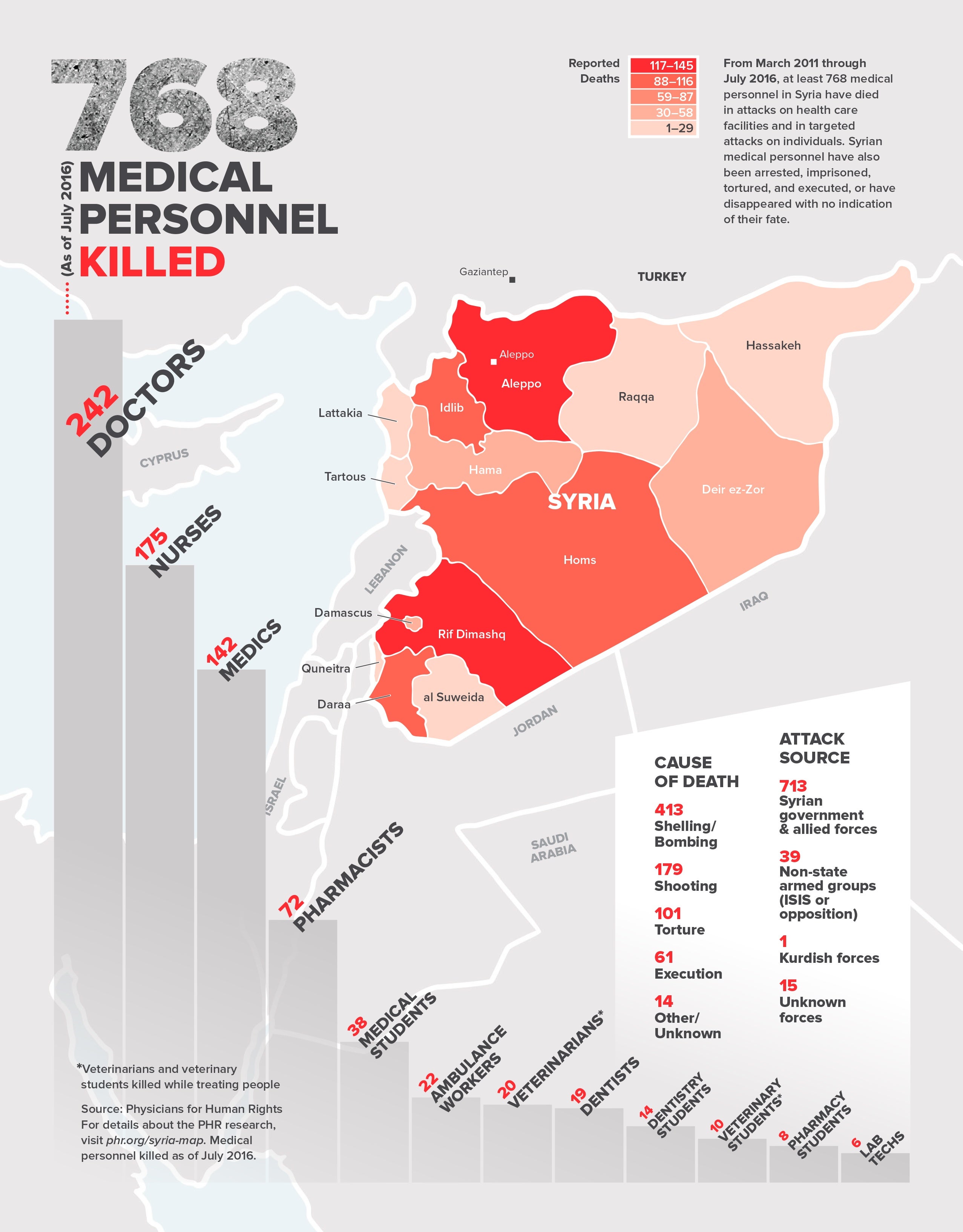

The carnage has not abated. As noted in the November 2015 report Aleppo Abandoned: A Case Study on Health Care in Syria, by the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), “Each of these targeted and indiscriminate attacks, whether the bombing of a hospital or the detention and torture of a doctor for providing health care, is a war crime. Given the systematic nature of these attacks, these violations constitute crimes against humanity. The Syrian government’s assault on health care is one of the most egregious the world has ever seen.” PHR has documented the deaths of 768 medical personnel from March 2011 through July 2016.

REVERSING THE “EPIDEMIOLOGICAL TRANSITION”

Syria, a middle-income country, decades ago went through the “epidemiological transition,” when noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and hypertension eclipsed infectious diseases as the major causes of death. Today, that trend has been reversed. And as Sparrow sees firsthand in her training sessions, the doctors who have chosen to remain in the country are often ill-equipped to deal with the war’s unleashing of injury and infection. “I used to see cancer patients,” one Syrian pediatrician told her. “Now I see diphtheria and polio. These are diseases we had forgotten.”

“I used to see cancer patients,” one Syrian pediatrician told Sparrow. “Now I see diphtheria and polio. These are diseases we had forgotten.”

According to Sparrow, “Syria has all of the developed-world problems—heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, kidney failure, Parkinson’s, and mental health issues, kids with cerebral palsy and epilepsy and cystic fibrosis—the usual problems that we see here in the United States. But they also face the war trauma, which is hideous, and then all of the infectious diseases that they have had to learn how to deal with: typhoid, tetanus, pertussis, polio, hepatitis A, on top of blood-borne diseases like hepatitis B and C and even HIV, because there’s no way to sterilize or to screen for these infections.”

Complicating the disaster, malnutrition is rife. “Imagine what would happen to the population of America if you suddenly lost all your dietary diversity and no one ever saw an egg and your access to milk and meat was so limited. People would start to develop dietary deficiencies,” says Sparrow. “In Syria, we don’t always see people starving to death, because they will first die of pneumonia, or measles, or the cold. But if they are severely malnourished, it’s hard to detect and treat infection, because when they’re starving, their bodies can’t mount an immune response, so there’s no fever.”

Severe acute malnutrition is especially catastrophic for children, because it not only leaves them vulnerable to infections such as measles and gastroenteritis but also makes them up to 10 times more likely to die from such diseases than a well-fed child. “The malnutrition is something I’ve never seen before to this extent,” Sparrow explains. “It’s different from the chronic malnutrition I used to see in Africa or Haiti. The Syrian children living under siege are being deprived of not just calories but also essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients necessary for emotional and intellectual development, let alone physical growth.”

BEARING WITNESS

As the war in Syria has dragged on, Sparrow has wielded her pen to excoriate not only the Assad regime but also global actors. In reportage that is eloquent and unsparing, she has taken the international aid community to task for public health failures in Syria. In a March 2016 article in Foreign Affairs, she wrote: “Since 2011, Syrian life expectancy has dropped a shocking 15 years—from 70.5 to 55.4. That is a shorter life span than even civilians in Afghanistan and Sudan expect today.” She has placed some of the blame squarely on major U.N. agencies, including the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the World Health Organization, and the World Food Program. “Because they have prioritized working with the Assad regime over gaining access to those in most acute need,” she wrote, these agencies “bear some responsibility for this tragedy.”

“The malnutrition is something I’ve never seen before to this extent,” says Sparrow. “The Syrian children living under siege are being deprived of not just calories but also essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients necessary for emotional and intellectual development, let alone physical growth.”

Sparrow’s testimony springs directly from her self-propelled mission of medical training, which has drawn heartfelt praise from her Syrian colleagues. “Actually, I can’t find words to talk about the work that Annie is doing for Syrian health workers,” says Mohammed Katoub, advocacy manager for SAMS in Turkey. “Those three to four days every two months now are not enough to meet all the Syrians who wait for her visit to consult her about something or even just thank her for raising awareness about public health issues in the country.”

Jaber Hassan, a Syrian critical-care doctor working in Tennessee who has led several SAMS teaching missions, sums it up this way: “The energy and compassion Annie has utilized in support of the oppressed Syrians are beyond description, unmatched by any non-Syrian human being.”

“WARS DON’T KEEP WORKING HOURS”

The tagline in Sparrow’s Google+ profile reads, “Used to run Global Fund’s Malaria program in Somalia. Now working on public health catastrophe in Syria, the rise of polio, ebola and other epidemic-causing agents, no time to run a bath….”

Sparrow’s life has little room for leisure. When she’s not crossing the globe to train Syrian doctors and nurses, document the attacks on health systems, and conduct on-the-ground research on the health outcomes of the human rights violations in Syria, she is an associate professor and deputy director of the Human Rights Program in the Arnhold Institute for Global Health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, in New York. She is also a practicing pediatrician in New York, where she lives with Roth and their 8-year-old son, Toto Sparrow.

But the war in Syria is always front and center in her mind. As Sparrow sees it, the world has become inured to the tragedy. “Every few months for the last three years, I’ve been going to the Syrian border and coming back here to the apathy,” she says. “‘Syria fatigue’ makes me furious. I feel as if I live in a steady state of ‘full catastrophe.’ The people around me—Ken, friends like Ellen, and those special few who support me professionally—are very precious, because wars don’t keep working hours. If Syrians don’t get to take a break, how can I?”

For the foreseeable future, she plans to keep up her travel to Syria’s borders with Turkey and Lebanon, where her Syrian colleagues and friends need her. “I’ll keep going back as long as what I have is of value to them,” she says. “I never imagined that all the medical knowledge and experience I had accumulated from working in affluent Western nations and in war zones would be needed for one single country. But over the years, Syrians have taught me that just showing up in solidarity is of tremendous value. It is the Syrians on the front lines who are the real heroes. I choose to stand with them and share their struggle.”

Jan Reiss is assistant director of development communications and marketing at the Harvard Chan School.