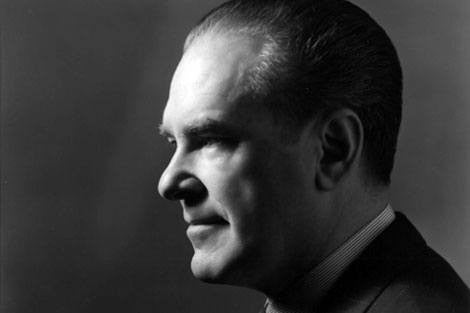

The warning you hear on every commercial airline flight—“In the unlikely event of a drop in cabin pressure. . . .”—is the result of studies conducted by Ross McFarland, who joined HSPH in 1947 as a member of the Department of Industrial Hygiene and who was an expert in the effects of altitude change and oxygen deprivation on pilots and passengers in airplanes.

Among other things, McFarland studied how oxygen deprivation can cloud judgment; looked at the size and illumination of instrumental panels on planes, to see if they were legible at extreme speeds; and worked with Pan American Airlines to study pilot fatigue on long flights. He corresponded with Amelia Earhart prior to her doomed flight around the world and was friends with Charles Lindbergh and many other pilots. Over the years he did work for the U.S. Navy, the Air Force, and NASA, as well as Pan Am. In 1962 he was named technical director of the Harvard-Guggenheim Center for Aviation Health and Safety.

Many graduates of McFarland’s program—as students, they were called “Ross’s boys”—went on to impressive careers. For instance, some helped select and test the first seven men known as the Mercury astronauts.

On a larger scale, McFarland’s work—which also included research on fatigue and work efficiency among Mississippi sharecroppers, and sources of energy and heat dissipation in muscle tissue in steel mill workers—focused on what he called “human factors.” His figured that if scientists could better understand the relationship between people and the machines they operate, they could design equipment that took into account human capabilities and limitations. Eventually, this discipline of “human factors” evolved into a familiar modern field: ergonomics.

* * * * *

Is there an event, person, or discovery in Harvard School of Public Health history that you’d like to read about? Send your suggestions to Centennial@hsph.harvard.edu.