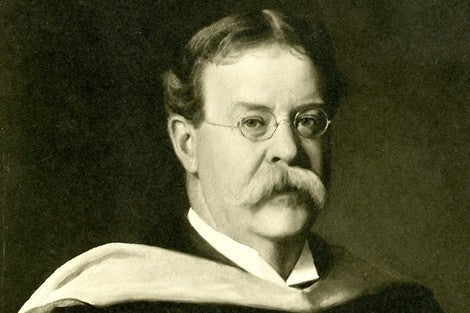

“The titan of a galaxy of giants—the inspiring center of this new movement—was William Thompson Sedgwick,” wrote one-time Sedgwick student Charles-Edward Winslow in a 1953 American Journal of Public Health piece on early 20th-century public health pioneers.

Sedgwick was one of the three founders of Harvard School of Public Health when it launched in 1913 as the Harvard-M.I.T. School for Health Officers. By this time, he was already a leading pioneer in the rapidly evolving fields of public health and sanitation. At M.I.T. Sedgwick headed the Department of Natural History, later known as the Department of Biology, where his protégés included future Harvard Professor of Sanitary Engineering George Whipple, who was himself responsible for involving Sedgwick in the nascent School of Public Health.

A researcher, writer, and teacher, Sedgwick published hundreds of papers and other writings. His studies of typhoid fever epidemics were described by Winslow as “classics in the field” while his book the Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Health, published in 1902, was “possibly the most potent single factor in awakening leaders in medicine, engineering, and science to the importance of sanitation in that era of rapid urban and industrial development,” in the words of one historian.

Among his students, Sedgwick inspired awe and veneration. Several years after his death, Winslow, Whipple, and a third former student, Edwin Oakes Jordan, penned the following remembrance:

“The really great teacher must give to his pupil three different things: a vision of the subject in hand in its relations to the evolving universe, a vigorously honest method of thinking and working so that the truth may be adhered to and if possible advanced, and an enthusiasm for service which will prove better even than the desire for fame as the compelling motive to make men ‘scorn delights and live laborious days’. These three gifts, and in rich measure, Sedgwick bestowed on his students.”

A riveting lecturer, Sedgwick had, according to Winslow, “an unusual gift for the apt and perfect phrase” (a claim that might well be disputed by readers of his New York Times diatribe against women’s rights) and an unswerving moral compass: “I recall a long talk he and I had on my personal qualifications and failings, at the close of which he said, ‘On the whole Winslow, I think you can be a very useful man’. Not a successful man, not a prosperous many—a useful man. That was his measure of the value of human life.”

Is there an event, person, or discovery in Harvard School of Public Health history that you’d like to read about? Send your suggestions to centennial@hsph.harvard.edu.