June 1, 2010 — More than two decades after the concept was first introduced in the United States, the designated driver is all grown up today. But, as you might expect, that driver still doesn’t drink while on duty.

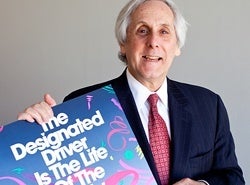

The idea that drinking and driving don’t mix is an old one, but it was during a period of heightened attention to the problem in the 1980s that the Harvard School of Public Health’s (HSPH) Jay Winsten (pictured at left) captured lightning in a bottle.

Winsten’s then-nascent Center for Health Communication scored a rare coup: creating the designated driver campaign in 1988, mobilizing Hollywood to support it, and cementing a new and enduring social reality in the public consciousness.

In reflecting on the campaign and discussing health communication today, Winsten, who currently serves as HSPH’s associate dean for health communication and as the Frank Stanton Director of the Center for Health Communication, said that the ground for the campaign’s success was prepared by years of highly visible work against drunk driving by the groups Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD). Their work in the early 1980s made an initial cut in the nation’s drunk driving death toll, but by the mid- to late part of the decade, Winsten said, the gains had begun to slip. The American public, Winsten said, had heard the message and agreed with it, but many still didn’t want to give up drinking and the socializing with which it was often associated. The designated driver concept allowed them to do that in an acceptable way — by taking turns as the sober driver.

“It was a positive message, lent social legitimacy to the option of refraining from drinking, and created social pressure to conform,” Winsten said. “We recognized the potential power of this and set out to make ‘designated driver’ a household word and to change the culture.”

While the designated driver concept took root in Scandinavia, the U.S. campaign that was born at the Harvard School of Public Health grew out of a tragic crash in which a popular WBZ-TV (Boston) newscaster, Dennis Kauff, was killed by a drunk driver in 1985, Winsten said.

“The Kauff tragedy made headlines and the local press corps was enraged and engaged,” Winsten said. “This was a target of opportunity for engaging with the media, and a teachable moment for the public.”

John Henning, an anchor at WBZ, joined with Winsten to mobilize Boston’s press corps and they kept the spotlight on the issue until the state legislature enacted tough new penalties for drunk driving.

Working first with WBZ and then an array of partners that expanded to include Madison Avenue marketing firms, TV networks, and Hollywood media, Winsten and his colleagues at the center studied Scandinavia’s experience and ran focus groups that revealed that the designated driver needed to be viewed as an integral part of the evening’s fun and not as a bystander. Hence the campaign’s slogan that the “designated driver is the life of the party.”

What may have cemented the idea in the public’s mind was Hollywood’s involvement. Winsten, working with top producers and studio executives, was able to get the concept written into the scripts of more than 160 episodes of the most popular shows of the time, including “Cheers,” “L.A. Law,” and “The Cosby Show.” Restaurants and taverns offered free nonalcoholic drinks to the designated driver. The concept endures today and is continually promulgated by a variety of proponents.

“Studies have shown that the custom of choosing a designated driver has become stably integrated into American culture, with a majority of the American public embracing the practice,” Winsten said. “The concept and practice [are] being passed from one generation to young people of the next.”

When the campaign began in late 1988, annual alcohol-related traffic fatalities stood at 23,626, with no decline since 1985; four years into the campaign, fatalities had dropped by 25 percent. Winsten credits a combination of factors for the drop, including new laws, stricter enforcement, and the designated driver campaign.

Reporting on the center’s campaign, The Chronicle of Philanthropy wrote, “Many grant makers say it was the success of the campaign that persuaded them that skillful work with news and entertainment media can bring about social change.”

The campaign’s success prompted the center to launch initiatives addressing youth violence, domestic violence, societal engagement by retirees, and good parenting. For the past decade, the center has spearheaded a national media effort to recruit mentors for at-risk youth, referring prospective volunteers to programs such as Big Brothers Big Sisters. The center’s mentoring initiative gained the support of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. More than 3 million young people are currently served by mentoring programs each year, compared with 300,000 when the center began the campaign, Winsten said.

In the 21 years since the designated driver first took the car keys, the media and communications landscape has undergone a radical transformation. Today, the center is examining new ways to reach important audiences with public health messages because the old ways are no longer adequate. The designated driver campaign hit at a time when the media market was dominated by the big three broadcast networks: ABC, NBC, and CBS.

“If we had one friend at each network — and we did — we could reach 75 percent of the public on an ongoing basis. That model is dead, due in part to fragmentation of the media marketplace. The tremendous growth of blogs, social media, and other user-generated content have rendered extinct the traditional public health model of unidirectional transmission of knowledge from experts to the general public. In the age of new media, the consumers have seized control over the content and dissemination of the message. The challenge for public health is how to reinsert ourselves into a conversation that is now going on without us.”

–By Alvin Powell

Appeared in the Harvard Gazette, Thursday, May 13, 2010