MỹDzung Chu, PhD ’20, explores the health impacts of housing inequities

October 28, 2o2o – As a resident of Boston’s diverse, working-class Dorchester neighborhood, MỹDzung Chu has learned first-hand, through her work with a local advocacy group focused on housing issues, about the shortage of affordable quality housing, about her neighbors’ fears of being displaced by new developments, and about how some landlords ignore necessary repairs—perhaps to drive tenants out in order to resell or re-lease the property for higher profit.

She knows that if people are worried that they can’t make rent, their stress can skyrocket; that if a landlord doesn’t repair a leaky ceiling or address mold or pest issues, it can lead to illness; that lead paint chipping off a windowsill can cause brain damage in young children.

Chu, a doctoral candidate in environmental-occupational health epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, has investigated how hazardous environmental exposures in neighborhoods across the U.S. have disproportionately impacted low-income, immigrant, and minority households.

In an essay she wrote last April for Environmental Health News on the topic of housing and environmental justice, Chu included a quote from one of her Vietnamese-American neighbors that drove home the connection between housing and health. “I call my landlord to fix the hole above my sink, but he ignores me,” the neighbor told her. “Water is leaking from the upstairs kitchen into mine. There is no heat in the main living areas of my apartment. I get sick a lot.”

Chu advocates for environmental health researchers to incorporate issues of housing security in their work. “If we focus just on the physical and chemical hazards of the indoor environment, how can we adequately address and prevent the root causes of health problems associated with housing insecurity?” she asked in her essay.

Chu is slated to earn her PhD in November. As she pursues a career focused on social determinants of health and environmental exposures in homes, workplaces, and neighborhoods, she says she’ll draw not only on her research expertise but also on what she’s learned from her fellow Dorchester residents’ housing struggles and the power they’ve built through community organizing.

She’ll also draw on the inspiring example of her late father, who spent a decade as a public health outreach worker in Springfield, Mass.

Like father, like daughter

When she was young, Chu sometimes tagged along with her father, Dương Chu, when he hosted community meetings for Vietnamese immigrant residents in Springfield, on topics such as nutrition or the risk of tuberculosis in the Southeast Asian immigrant and refugee population.

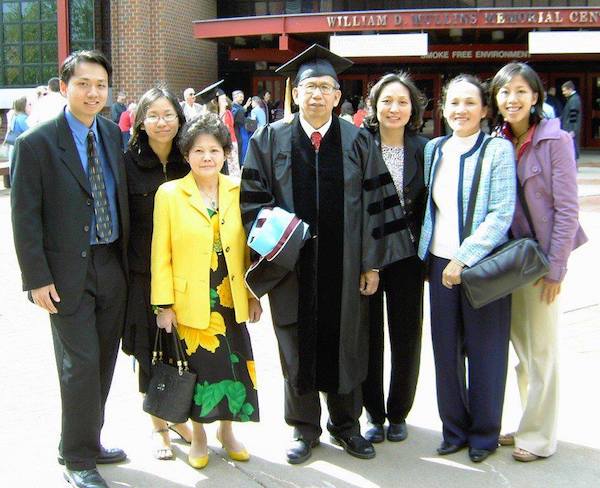

In mid-life, Chu’s father earned a doctorate in education at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst; his dissertation focused on culturally competent health care for Vietnamese adults and elderly in the Springfield area. Observing her father’s commitment to the health of the Vietnamese community and his educational achievements deeply influenced Chu’s own decision to pursue a PhD and career in public health. “In the back of my mind, I thought, ‘If he could do it—and he didn’t even know English when he came to the U.S.—then I could do it,’” she said.

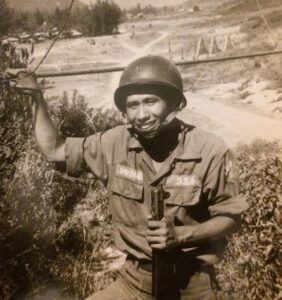

Chu had other reasons to admire her father. In Vietnam, he’d served as an Army officer in charge of communications for South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Following the South’s takeover, he was sentenced to three years in a “re-education” prison in southern Vietnam. After an escape attempt he was captured and sentenced to another three years in northern Vietnam, where conditions were worse. He survived that experience by relying heavily on his faith, said Chu, and the family was able to immigrate to the U.S. in 1992 as part of a U.S. government program for former political detainees.

As an undergraduate at Smith College, Chu studied neuroscience, with help from the Gates Millennium Scholarship, which supports outstanding underrepresented minority students with significant financial need. She considered going to medical school, but delayed that goal in order to study environmental and occupational health and epidemiology at Emory University. While there, she interned at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Agency for Toxic Disease and Substance Registry (CDC/ATSDR). During her time at Emory and at CDC/ATSDR, she became intrigued with how environmental toxins can impact health—for instance, about the dangers posed by chemical exposures in nail salons, where many workers are Vietnamese. “I learned so much and was inspired,” said Chu. “I knew that public health was the right career path for me.”

After getting her master’s degree at Emory, Chu worked for four years as an epidemiologist for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. One project she led was characterizing work-related injuries among local government workers using multiple data sources, and she and colleagues produced the first statewide report on the topic. “I developed a love of using data for action—linking data to address important public health questions and to inform interventions,” she said. Eventually she realized that she wanted to do a deeper dive into research.

Bettering her community

She chose Harvard Chan School in order to work with Gary Adamkiewicz, assistant professor of environmental health and exposure disparities. Chu was impressed with Adamkiewicz’s focus on how housing, communities, and neighborhoods shape health. She worked with his research team and collaborators in the Harvard Chan School-Boston University Center for Research on Environmental and Social Stressors in Housing Across the Life Course (CRESSH) to identify drivers of disparities in indoor air pollution exposure across homes in the city of Chelsea and in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. To ensure that the Vietnamese-American populations in these communities were represented in the research, she helped secure funding from the Harvard Chan-NIEHS Center for Environmental Health to translate recruitment materials into Vietnamese and helped recruit Vietnamese participants for the project.

“I have been impressed by MyDzung’s consistent passion and commitment to better her community, as well as her purposeful engagement of research as a tool in which to do so,” said Adamkiewicz. “She is one of the smartest, most hard-working and passionate students I have worked with.”

At Harvard Chan School, Chu served as one of the leaders of the Environmental Justice Student Organization and helped run a daylong conference in spring 2019 on environmental and food justice. In Dorchester, she became involved in a grassroots community coalition called Dorchester Not for Sale, which aims to increase affordable housing, promote equitable community development, and limit the displacement of residents. She has helped the group with data analyses and outreach support.

For her dissertation, Chu decided to examine environmental health disparities in U.S. homes and neighborhoods, looking at both the source of environmental hazards and the social determinants that drive disproportionate risk across groups, with a particular focus on where people were born. “No study to date has comprehensively characterized residential environmental exposure disparities by nativity status at the national level,” Chu wrote in her dissertation.

Her research drew on comprehensive nationwide data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s American Housing Survey, which includes information on the quality and cost of homes across the country, as well as characteristics of the people who live in those homes. Chu looked at environmental risks such as lead paint, mold, pests, and indoor air pollution, as well as factors such as crowded conditions and kitchen and bathroom deficiencies. Her research identified several housing hazards that were higher among foreign-born households, and also confirmed what other studies have shown—that people of color and low-income populations in the U.S. face disproportionate risk from environmental health hazards. It also showed that, overall, Black U.S.-born residents face greater risk than those who are foreign-born. “Researching immigrant health has really illuminated the persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities that we see in the U.S.,” said Chu.

Chu started a new job in September, virtually, as a postdoctoral scientist at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health. She is working with Ami Zota, an associate professor in GWU’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, studying the impact of federal housing assistance on residential environmental exposures among low-income communities.

“I’m engaged in research that I’m passionate about—connecting environmental health hazards with housing justice and housing policy,” said Chu. “And centering the work on populations most at risk.”

photos courtesy MỹDzung Chu