October 3, 2012 — Quantitative Methods Course Teaches Building Blocks of Public Health Research

It’s time for biostatistics and epidemiology class. The professor is discussing Scotsman James Lind, who, in the mid-1700s, conducted one of the first-ever clinical experiments. Lind studied the way different foods affected sailors sick with scurvy and found that only those who added citrus fruits to their regular diet recovered. It’s an interesting lecture. But there’s no one in the classroom.

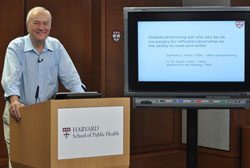

Not yet, that is. That’s because the lecture is one of many currently being recorded in the state-of-the-art Leadership Studio at Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) as part of a brand-new online introductory course in epidemiology and biostatistics that begins October 15, 2012. The new course, “Health in Numbers: Quantitative Methods in Clinical and Public Health Research,” is one of the two inaugural courses being offered by Harvard this fall as part of edX, the online education platform launched last May by Harvard and MIT; the University of California, Berkeley joined in July.

EdX is a nonprofit global venture aimed at advancing online learning and generating a wealth of information about how students learn and how to teach them most effectively. Seven edX courses are being offered in fall 2012: three from MIT and two each from Harvard and UC Berkeley. Topics include computer science, chemistry, electronics, and public health.

The HSPH course is being co-taught by E. Francis Cook, professor of epidemiology, and Marcello Pagano, professor of statistical computing. Already, thousands of people from all over the world have signed up.

“We have been exploring online options for some time, but edX catalyzed both our thinking and our response,” said David Hunter, dean for academic affairs at HSPH, who is coordinating the School’s edX participation. “Assembling and retaining a critical mass of faculty to teach public health is a challenge anywhere, but is particularly difficult in resource-poor countries. We look forward to working with our partner institutions to find ways that the edX courses can help their faculty execute a more diverse array of courses, and expand public health teaching around the world.”

Building blocks of public health

The HSPH course is a perfect first offering for the edX platform, said Cook. The course includes the buildings blocks of public health research—biostatistics and epidemiology—and paves the way for anyone wanting to go further in the field. In addition, offering the course to people everywhere dovetails perfectly with the work done by HSPH students, researchers, and faculty.

“The mission of this school is to improve the health of world,” said Cook. “With this new course, we have an opportunity to really have a huge impact.”

Added Pagano, “To address this many students, I would have to teach for another hundred years. I think making these courses available for free to the world is this generation’s equivalent of the free public library.”

Nuts and bolts

Since early September, Pagano and Cook have been spending two to three days each week filming lectures in the studio on the 10th floor of the Kresge building. It’s a bit odd to lecture to a camera, Pagano said, so he tries to pretend it’s a person. He does appreciate the fact that the video format allows him and Cook to do retakes—a real advantage over lecturing in a traditional classroom, where a professor can have good days and bad days. “Regular class is like a play, but this is like a movie,” says Pagano. “We can make it perfect.”

The edX website advises potential students that “Health in Numbers” requires 7 to 10 hours a week of coursework, including videos, online readings, and homework. Cook gives the epidemiology lectures, Pagano teaches biostatistics, and four postdocs present labs. After each of the modules—which are packaged in 10- to 20-minute chunks—students will be asked to participate in an activity, such as doing calculations or answering a few questions. At the end of each week they will be quizzed online with multiple-choice, yes-or-no, or mathematical questions, and their work will be automatically graded. New content will be posted each week.

Students who participate must agree to an honor code; they will receive a certificate of mastery when they complete the course.

The good, the bad, and the exciting

Cook and Pagano are excited about the many benefits to students of taking a course online. Enrollees will be able to control the pace of their studies by choosing when to “attend” classes; speeding up, slowing down, pausing, or replaying videos; or skipping sections. In this way, it will be a bit like having a private tutor, Pagano said.

Students will be able to discuss course content in chat rooms with teaching assistants or with fellow students from around the globe. And course organizers are thinking about ways to expand the use of the chat rooms in the future. For instance, groups of students from a certain country or region, say, southern Africa, could participate in chat rooms in their native languages or arrange to meet in person. Perhaps alumni in those regions could be invited to join the local chat rooms to offer their expertise.

There are some potential drawbacks of teaching online, say Pagano and Cook. They won’t ever meet their students, learn their names, or chat with them in the cafeteria. They won’t be able to see the expression on students’ faces (Pagano said blank stares are usually an indication that he hasn’t been clear.) There’s no opportunity for back-and-forth discussion during class. Cook said he also wonders how many students will drop out—that, because they don’t have to pay for the course, they might be less “invested,” literally.

On the other hand, said Pagano, he and Cook are creating a high quality course that is available for free to the world and “that excites me,” he said.

The new public health course, along with other edX offerings, will become part of a growing library of courses available for years to come—and they will be valuable to students both online and on campus. For example, in the future, on-campus students might view lecture sections of courses online, thus reserving class time for discussion. In addition, Harvard educators will be able to examine course metrics—such as how long students spend on particular sections, or which parts they speed up, slow down, skip, or replay—to learn what to change or improve. Such information could provide insight on how students learn best and how technology can help facilitate effective teaching.

Said Cook, “We are very intrigued, very excited about this course. I think this is going to have great benefit not only for the students who take it, but for HSPH.”

photo: Aubrey LaMedica