February 18, 2016 — A unique winter session practicum at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, offered in conjunction with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is giving students valuable experience in how to evaluate public health programs—and is helping state and local public health officials around the country do the same.

During the three-week intensive course—one of the highest-rated at the School in student course evaluations, with 60-80 applicants for 20 spots—students spend one week at the CDC in Atlanta learning about program evaluation; another week working with CDC and state or local public health officials to produce draft evaluations of programs; and the last week back at Harvard Chan School, finalizing the evaluations. Those finished evaluations—which are graded and include professors’ comments—are then shared with state and local officials.

“This course is unique because it’s actually work, with the students acting as consultants,” said Marie McCormick, Sumner and Esther Feldberg Professor of Maternal and Child Health at Harvard Chan School, who co-teaches the course with Mary Jean Brown, chief of the lead poisoning prevention branch at the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health and adjunct assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences at Harvard Chan. Fifteen years ago, shortly after starting at the CDC, Brown helped develop the course after learning that state and local health departments around the country were relying on expensive outside consultants to conduct program evaluations. Brown, who’d taught program evaluation at Harvard Chan, realized “that we could not only teach students about program evaluation, but we could also teach state and local health departments, and even folks within the CDC and other government agencies.”

Since the program’s inception, more than 340 students have participated, working with 168 programs around the country, Brown said.

This past January, the Harvard Chan students spent what Brown termed a “very intense” week at the CDC learning the nuts and bolts of program evaluation. Also participating were 13 state officials and several CSTE (Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists) fellows and CDC staff assigned to different states.

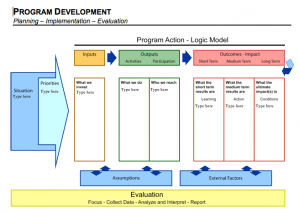

One of the core lessons was how to produce a “logic model”—essentially a roadmap, laid out in connecting blocks of information on one page, that lists all the components that need to be considered in evaluating a program, including its costs, activities involved, and desired impacts. “If you can’t get these components right, you really can’t do the evaluation,” McCormick said.

The week in Atlanta also provided opportunities for state officials to learn from each others’ experiences. “Everyone gets to hear what the others are doing,” said Brown.

The following week, the students fanned out—two each to 10 different states, including Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming—along with the participating state and federal officials, to work on evaluations for programs ranging from curbing substance abuse to screening for depression to reducing sudden unexpected infant deaths.

This stuff is hard

Students said that working closely with state and local officials helped them realize just how complex it can be to run public health programs.

Katie Cueva, a doctoral student in social and behavioral sciences and nutrition, worked in Minnesota on a program for Native Americans aimed at teen pregnancy prevention and sexual health education. She said a key benefit of the practicum was that it gave the state public health officials—who want to reach more youth and improve the program, but don’t necessarily agree on how to do it—the opportunity to think through, together, how best to shape and implement their program, “and for us to share an outside perspective.”

Ellen Fugate, a master’s student in health policy and management, worked in Louisiana on a proposed program to reduce substance abuse disorders among Medicaid-enrolled mothers, and, by extension, to their children who may go on to struggle with withdrawal symptoms in their first months of life. Fugate said the practicum helped her to see not only the pervasiveness of the opiate abuse problem, but also “the sheer number of components you have to take into account” in program evaluation.

She also learned that choosing the best indicators of program success can be challenging. “Sometimes, what you think may be a good measure ends up not actually measuring what it’s intended to,” she said. “So you have to think really deeply about these things.”

For example, Fugate and her team initially wanted to use Medicaid claims data to determine the frequency of substance use disorder screenings and brief interventions. But because the Medicaid reimbursement rate for these services is low—and because some doctors may not even know that reimbursement for these services exists—the team realized that using claims data would be an unreliable measure. Instead they recommended that screening frequency and interventions be documented by the doctors themselves.

An outsider’s view

State public health officials who participated in the practicum said they appreciated the Harvard Chan students’ outside perspective and attention to detail.

“The students bring fresh eyes to our projects, which helps us clarify and think through exactly what our program is and how to evaluate it, and what’s doable and not doable,” said Debra Kane, MCH epidemiologist-CDC assignee for the Iowa Department of Public Health, who worked with students on a program to reduce preterm and early-term births by increasing the use of progesterone, a hormone that helps prepare the uterus for pregnancy and nurtures the fetus. “It was a really positive experience.”

In Massachusetts, Harvard Chan students helped evaluate the ramifications of a possible change to the state’s lead poisoning prevention program for children under age 6. Under the proposed change, the definition of lead poisoning would be based on blood lead levels significantly lower than the cutoff currently used. CDC recommendations are being used to inform the state’s decision, according to Sarah L. Stone, CDC/CSTE applied epidemiology fellow at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, one of several Massachusetts DPH workers who participated in the practicum.

Lowering the lead threshold would hopefully improve children’s long-term health, Stone said. Lead poisoning is also a health equity issue because it already disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities and children in families with lower incomes, she noted.

However, after discussions with DPH staff and using a logic model, the Harvard students realized that lowering the threshold might in fact have some negative consequences. That’s because a determination of lead poisoning leads to mandated intervention in homes, such as removing lead or encapsulating it, and this might make unscrupulous landlords less inclined to rent to families with young children because of the cost involved. “That could mean a decrease in the amount of available housing, which is already in scarce supply, especially for families with lower incomes,” said Stone.

Using the logic model helped bring the information about potential housing challenges to the forefront. “The logic model is an ideal tool to consider the complex relationship between activities and outcomes,” Stone said. “No amount of lead is good,” she added, “but these sorts of consequences need to be taken into account as the DPH considers changing how lead poisoning is defined.”

Brown said it’s particularly valuable for the Harvard Chan students—typically high achievers accustomed to success in their endeavors—to confront “complicated programs with a lot of moving pieces.”

Joshua Jeong, a doctoral student in global health and population, agreed. He worked with the Vermont Department of Health on a program aimed at increasing screening for depression among parents. “I think it’s valuable to have grad students who kind of live in their own bubble work in the field to see that things don’t actually work the way we talk about in the classroom,” he said.

photos courtesy Marie McCormick, Katie Cueva, Joshua Jeong