April 6, 2017 – A renowned community organizer told a rapt audience that organizing—bringing people with a common purpose together to create change—could be an effective way to improve people’s health at a time when political realities appear to threaten it.

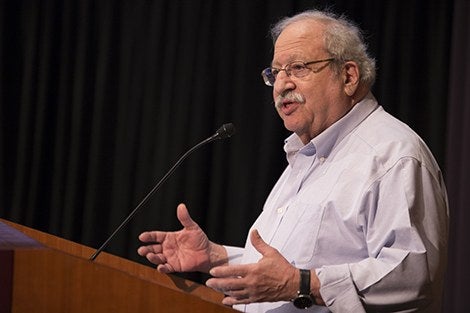

Marshall Ganz, senior lecturer in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, offered strategies for organizing before a crowd of hundreds who gathered at Harvard Medical School’s Joseph B. Martin Center Amphitheater on April 4, 2017.

The event, “Organizing for Health: People, Power and Change,” was hosted by the deans of Harvard University’s three health schools—Michelle Williams of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, George Daley of Harvard Medical School, and R. Bruce Donoff of Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

The idea for the event was spurred by what Daley called “a sense of urgency” and what Williams called “a sense of shock.”

Daley and Williams listed worrisome moves by the Trump Administration, including proposed deep budget cuts to the National Institutes of Health and the Environmental Protection Agency, efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, and attempts to impose a travel ban that could prevent colleagues and collaborators from working together.

Citing misinformation that’s being spread about everything from vaccines to climate change, Daley asked, “How are we going to face the remarkable threats against health, against wellbeing, and how are we going to be able to serve people in the absence of rational thinking?”

“It has become clear that our community is hungry for information about how to harness what we feel as concerned citizens and humanitarians, and what we can do—as scientists, as health care professionals, as policy experts—to engage in correcting and moving us forward, not backward,” said Williams, who introduced Ganz.

An organizing ‘how-to’

Ganz is a veteran community organizer who participated in the civil rights movement, in the California farm workers labor movement led by César Chávez, and in the political campaigns of Robert Kennedy, Howard Dean, and President Barack Obama.

Actions taken by the Trump Administration “have evoked a kind of extraordinary solidarity in the face of a common threat,” said Ganz. “The challenge is to figure out how to turn that into solidarity on behalf of common purpose.”

He outlined five basics for effective organizing: People need to build relationships based on shared purpose; share stories about what is motivating them toward change (a “public narrative”); work in leadership teams at the community, regional, and national levels; develop strategies for using whatever power and resources are available to them; and, finally, take action.

He outlined five basics for effective organizing: People need to build relationships based on shared purpose; share stories about what is motivating them toward change (a “public narrative”); work in leadership teams at the community, regional, and national levels; develop strategies for using whatever power and resources are available to them; and, finally, take action.

As one example of effective organizing, Ganz cited the mid-1950s Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott, which eventually led to a U.S. Supreme Court decision ordering the city to integrate its bus system. African Americans in Montgomery didn’t have traditional political power, but by banding together to walk to work to deny the bus company its fares, “all of a sudden the bus company was more dependent on the people than the people were on the bus company,” said Ganz. “They inverted the terms of power. It took sacrifice. It took a year of struggle, but they won.”

Conflict is a critical part of change, Ganz added. He said it’s important to “make the conflict constructive, make it creative. It takes courage and it takes risk.”

Creating changes in health care

Two experts from ReThink Health gave examples of organizing practices that led to successful change in health care. ReThink Health, which works with communities, regions, and states to improve health and health care systems, was launched a decade ago by a team that included Ganz as well as Donald Berwick, former head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), who also spoke at the event.

Kate Hilton, a faculty member at ReThink Health and IHI, described how McLeod Regional Medical Center in Florence, South Carolina boosted adoption of the Surgical Safety Checklist by organizing teams across the hospital. Groups of employees shared stories about why using the checklist mattered to them and they promoted its use. After a three-month campaign, use of the checklist leapt from 30% to 90%.

She also discussed a project in Columbia, South Carolina, in zip code 29203, where low-income residents struggle with poor health, health inequities, and lack of insurance. To address those issues, local leaders forged a coalition called “Healthy Columbia” that included health care institutions, government, and community and religious organizations. The effort led to a host of volunteer-led events ranging from health screenings to Zumba classes to financial planning workshops.

Predrag Stojicic, senior scholar of engagement and stewardship at ReThink Health, talked about how people in his home country of Serbia banded together in 2009 to fight the widespread practice of providers taking bribes to provide health care. A small group of leaders started a website called “What’s Your Doctor Like?” through which people could rate their doctors and report corruption, and recruited volunteers from around the country to promote the effort. The website drew 30,000 visitors in its first week—then the government shut it down. After street protests, the government agreed to negotiate with protestors—and now citizens are free to post information about their doctors and report bribe-taking.

“We learned that organizing is a great way to enable ordinary people to deal with complex issues,” said Stojicic. “We also learned that power should be built by the resources that people have—and sometimes it’s as little, but as powerful, as their voice.”

Audience members also heard pitches about current organizing projects from students from each of Harvard’s health schools—and were invited to sign up to get involved.

After hearing the compelling presentations, Berwick said he thinks that mastery of organizing skills should be a core tool for health care leaders. And the Dental School’s Donoff suggested that organizing might be an effective way to address a longstanding problem—Medicare’s lack of dental benefits, a suggestion that brought a hearty round of applause.

photos: Sarah Sholes