[ Winter 2013 ]

How four HSPH alumni are helping Bhutan—the Himalayan home of “Gross National Happiness”—achieve its lofty goals

Atti-La Dahlgren recalls the moment that his public health life took a sharp turn toward the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan. It was May 2002, at the World Health Organization’s annual World Health Assembly. Dahlgren, MPH ’00, a global health physician in Geneva, was waiting for a bus home when a friend passed by and invited him, on the spur of the moment, to a closed-door meeting of health ministers.

“I listened as several ministers stood up to talk. It soon became obvious that while the name of the minister or the country changed, each 15-minute speech was more or less the same—until the health minister from Bhutan took the floor,” Dahlgren recalls. “He spoke without notes. He explained that his was one of the poorest countries in the world. And he said he was going on a 560-kilometer walk across the country, village to village, to talk about the importance of public health. He spoke freely, from his heart. I was completely captured.

Call it karma. “When I became involved with Bhutan,” says Dahlgren, now president of the International Bhutan Foundation, “I learned that nothing happens by coincidence.”

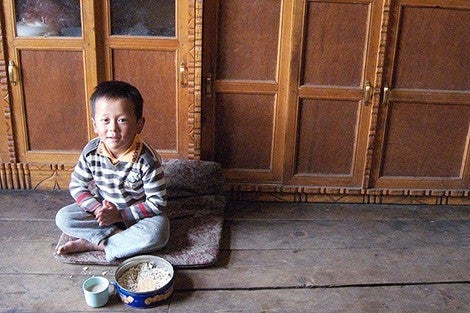

Their shared mission has taken them off the beaten path. Asked to point to Bhutan on a world map, most people would be stumped. Half the size of Indiana, wedged between India and China, this compact nation of 700,000 has spent most of its history in self-imposed isolation. Never conquered or occupied, it tentatively began modernization in the 1960s. Internet and television didn’t arrive until 1999.

Today, celebrated for its pristine environment and its vow to become a 100 percent organic food producer, Bhutan is probably best known for its guiding philosophy of “Gross National Happiness,” or GNH, which strives to balance economic development with spiritual well-being. But that novel policy is being put to the test. Newfound consumerism, fueled by rural-to-urban migration, is partly behind a wave of unprecedented public health challenges, from obesity to drug use. Vaulting from a preindustrial culture to the information age in just 50 years, Bhutan has become a living laboratory for dealing with the challenges of rapid modernization. “For a country that is not an easy place to get around, they have managed to achieve a 93 percent child immunization coverage—which is very impressive,” says Richard Cash, senior lecturer on global health at HSPH and an international leader in developing public health solutions for low-resource nations.

“The most striking thing about Bhutan is that, as a part of their movement to secure Gross National Happiness, they have made affordable and accessible health care central to public policy,” adds Parveen Parmar, a faculty member of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. In 2009, as a consultant on emergency medical care to Bhutan’s Ministry of Health, Parmar traveled to hospitals and clinics throughout the country. “You get a sense that once a problem is identified, everybody is on board to find a solution. That top-down dedication is a model, not only for small, developing nations, but for larger ones as well.”

Crossroads of old and new

perhaps a model for other small countries, because it puts

health and social well-being at the forefront of development.”

—Atti-La Dahlgren, MPH ’00, president, International Bhutan Foundation

Kathy Morley, a Boston-based emergency medicine physician, and her husband, Michael Morley, an ophthalmologist, are working at this crossroads of old and new. Over the past decade, earning complementary degrees at HSPH (she in global health, with a focus on health systems; he in health care management), they have fashioned themselves as a public health team in their volunteer assignments abroad. After projects in Cambodia and Thailand to deliver advanced eye care surgery, they brought their expertise to Bhutan in 2004—drawn as much by its spiritual culture as by its pressing public health needs. Michael set up Bhutan’s first laser surgery equipment to treat diabetic retinopathy, and the couple collaborated with the WHO on a Rapid Assessment Avoidable Blindness survey.

More recently, the Morleys have joined forces with the nongovernmental organization Health Volunteers Overseas to buttress Bhutan’s emergency care system. The collaboration, funded by the Washington, DC–based Bhutan Foundation, includes physicians at the University-wide Harvard Humanitarian Initiative.

With traumatic injuries—often the result of road accidents—a major cause of death in the country, Kathy helped develop a National Emergency Medicine Course for JDW National Referral Hospital in the capital, Thimphu. The hospital has no emergency medicine doctors—a situation reflecting a dearth of specialists throughout the nation. This past September, the education module was used to train some 20 physicians managing emergency and trauma care. The training will pay off not only with accident victims, but also with victims of other common emergencies, such as children choking or women suffering from ruptures caused by ectopic pregnancies.

Fear of seat belts

In Bhutan—where subtropical southern lowlands rise to sacred, unclimbed peaks exceeding 24,000 feet—many grievous injuries occur when cars veer off the country’s narrow, vertiginous roads. Bhutanese dislike wearing seat belts, fearing the belts will trap them in falling vehicles. Kathy Morley wants to conduct a study to see if that tenacious cultural belief is valid. “You need data to change people’s minds,” she says. “And when it comes to research, the great thing about Bhutan is that it’s a small country and all health care is delivered through the same system, so you can do a study on a national basis. The only barriers are geographic.”

Both Morleys are also working to improve the efficiency of Bhutan’s underfunded health care system. To this end, they created a prototype bar code system in which each patient receives a piece of paper that is scanned as he or she moves through treatment—a kind of high-end time stamp that will enable hospital managers to analyze and improve patient flow. “This was straight HSPH teaching,” says Michael Morley. “It’s not very sexy, but you can squeeze improvement in capacity and output just by working smarter—making relatively simple improvements that, ideally, cost no money.” The bar code project is expected to be most valuable in well-defined environments such as outpatient clinics and operating rooms.

Isolation to inspiration

Bhutan launched its health system in 1961, when the country was just beginning to open its borders. At the time, Western medicine was virtually nonexistent: the nation had two hospitals, two doctors, and two nurses. TB, leprosy, and malaria were common, and 80 percent of women suffered goiter from iodine deficiency.

In the last half century, guided by a fierce commitment to public health and a royal family that has spearheaded many progressive health campaigns, that dire picture has spectacularly improved. Health care has been deemed a right, not a privilege; the government pays for all treatment (including treatment abroad), and there are no private medical practices. Bhutan’s system seamlessly integrates Western with cherished traditional therapies that date back 2,500 years and have been found effective for some chronic ailments, both physical and emotional.

Perhaps most impressive, in dauntingly mountainous terrain, Bhutan has built a unique network of 178 basic health units—small, spare medical facilities that can provide vaccinations, midwife care, and simple medical interventions—and 654 outreach clinics, located so that treatment is always available within a three-hour walk (not an unusual trek for the rural Bhutanese). Village volunteers serve as intermediaries between often-isolated pockets of people and formal health care institutions. About 90 percent of Bhutan’s citizens have health coverage—with most of the remaining 10 percent high altitude nomadic herders who cannot be easily reached.

Today, Bhutan’s major health threats include acute respiratory infections (worsened by wood fires in the countryside), diarrheal diseases, and skin infections. But as in many developing nations, the afflictions of poverty are fast becoming eclipsed by the afflictions of excess and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. Noncommunicable diseases such as cancer and heart disease account for 31 percent of deaths, and stroke, hypertension, and diabetes are on the rise. As Tashi Wangdi, head of the Internal Medicine Department at JDW National Referral Hospital, wrote in 2012, “Bhutanese might be seeing the beginnings of an unhappy bargain: of living longer, but of also being sick longer, and from new and frightening diseases.”

To keep up with the shifting scenario, Bhutan needs to more than double its health workforce to reach WHO standards. With 2,000 medical workers in the entire country, including barely 200 doctors, virtually every aspect of care is strained. In an effort to reverse the picture, the nation’s Royal Institute of Health Sciences in 2010 started a bachelor’s of public health program for workers in the country’s frontline basic health units, to upgrade their clinical and research skills. The course will prepare them for everything from outbreak investigations to home-based care for stroke victims.

The price of equity

Fresh out of medical school, Gepke Hingst journeyed to war-torn Afghanistan in 1983, when the Afghan government and its Soviet backers were battling a Muslim insurgency. Though she had contemplated a position in Bhutan, at the urging of a Buddhist friend, what followed instead were stints in Africa and South Asia.

Not until 2006 did she became UNICEF’s country representative in Bhutan. What took so long? “Sometimes,” she says, “karma makes you wait.”

At HSPH in the mid-’90s, Hingst had focused on global health. “As a doctor, you’re told that disease is disease—social and economic background don’t matter. But when you work for a long time in developing countries, you see what I call the ‘repetition of horror.’ Harvard teaches you to address inequities and really arrive at public health.”

In Bhutan, Hingst encountered a nation bent on avoiding the repetition of horror that springs from poverty and certain cultural norms. UNICEF is mandated by the UN to advocate for children and to promote the equal rights of women and girls in political, social, and economic development. In Bhutan, this mission has taken Hingst on far-flung expeditions, such as 24-day excursions through high passes, ice-cold streams, and steep valleys to the remote districts of Laya and Lunana in the northwest peaks where Bhutan borders Tibet. She has trekked with outreach workers from a basic health unit on a two-day journey to a village of 19 households at an altitude of over 12,000 feet—all to vaccinate six children and attend to other essential needs.

“They do it every month because there are 19 households there: 19 households that have the right to health care,” says Hingst. “They do family planning, AIDS education, vaccinations. They bring medicine. They treat eye problems and do dental care.”

She adds: “Because Bhutan’s population is so scattered and there aren’t that many people, you will never achieve cost effectiveness. The economy of scale doesn’t work here. This is the cost of equity.”

A tide of construction

But as the cultural fabric of Bhutan shows signs of fraying, health equity has acquired a new meaning. Today, the graceful terraced rice paddies surrounding the capital, Thimphu, are giving way to a massive tide of construction and a torn cityscape of dust, debris, and spindly bamboo scaffolding.

“For me, what Bhutan illustrates is that progress is not without a price,” says Hingst. “People are moving from rural areas to the cities. The challenges for children are dramatic. In urban areas, life is expensive—both parents start to work. Who is taking care of the child? Is it going to be a slightly older sibling or a young niece from the village who will sacrifice her own education—child nannies caring for three- or four- or five-year-olds? Where first we were talking about the need for vaccination and access to health care and schools, now we’re talking about the risks of drug abuse, juvenile crime, broken families.”

According to a recent national survey, 18 percent of children are engaged in child labor and 30 percent of girls are married illegally before the age of 18. As Thimphu and other cities see growing numbers of children forced to fend for themselves emotionally, Hingst is most proud of UNICEF supporting Bhutan’s 2011 Child Care and Protection Act, which is intended to safeguard children against violence, abuse, and exploitation.

“You don’t have to suffer.”

After raising money for the health minister’s 2002 walk across the country, Atti-La Dahlgren in 2006 founded the International Bhutan Foundation, which focused on programs devoted to child development and to the welfare of youth and women. Today, he has turned his attention to educating the Bhutanese public about cancer—an almost taboo topic in the country. “Everybody knows somebody who has had cancer. But there’s a cultural belief that if you get sick, it’s a result of your actions in this life or in a previous incarnation. So it’s not talked about,” he says. “There’s an acceptance of suffering. We need to be able to explain, in Buddhist terms, ‘It’s OK to be treated, you don’t have to suffer.’”

Compounding the problem, Bhutan has only two oncologists and no facilities for cancer treatment. According to Dahlgren, “Many people suffer from cancer but are either not diagnosed in time, wrongly diagnosed, or not diagnosed at all.” As a result, most patients are sent to India for costly late-stage interventions.

“There’s a huge need for awareness—about types of cancer, prevention, and the need for better diagnostics and treatment,” says Dahlgren. He wants to establish a national cancer society to educate people and encourage patients to come out and speak about their disease. But Dahlgren says a national cancer treatment program would have to piggyback on the existing rudimentary health system, requiring more people, more equipment, and more labs—a daunting proposition in a country that is still desperately resource-poor. He is now reaching out to public health experts who can lend their skills to launching such an effort.

Doing what needs to be done

Despite these hurdles, material and cultural, the HSPH alums who have devoted much of their careers to Bhutan are not only optimistic about the country’s prospects—they feel that this nation has much to teach the world. “Compassion and the idea of looking after each other are integrated into the culture,” says Dahlgren. “Bhutan has the potential to serve as an inspiration and perhaps a model for other small countries, because it puts health and social well-being at the forefront of development.”

Gepke Hingst, who left her UNICEF post in the fall of 2012 after an unusually long six-year assignment, agrees that Bhutan’s vision for public health is inseparable from its spiritual outlook. “Buddhism is founded on the idea of interdependence—interdependence with nature and interdependence with other people.”

In Bhutan, she says, this sense of spiritual connectedness translates directly into public health practice. “Officials don’t shy away from difficult issues—they simply do what needs to be done. The beauty of Bhutan is that they mean it.”

Madeline Drexler is editor of Harvard Public Health.