Study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible. – Richard Feynman

Dysregulation of body weight is a major public health issue. Excessive body weight, or obesity is a major risk factor for metabolic diseases, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disease, depression, and certain types of cancer. The continuing rise of the already pandemic level of obesity rate represents a tremendous medical, social and economic burden for individuals and society. At the other end of the spectrum of body weight, the involuntary loss of body weight, or cachexia, is widely present in diseases including cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and many infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and AIDS. Thus, understanding the control of body weight will have tremendous impact on public health.

The Hui laboratory aims to understand the fundamental mechanisms of regulating body weight and target these mechanisms to treat obesity and cachexia. To this end, we take the systems biology approach, characterized by quantitative measurement and holistic modeling. This is exemplified by our approach of in vivo flux quantification. Fluxes are the most fundamental functional property of metabolism. Their systematic quantitation holds the potential to transform the field of mammalian physiology. This approach, however, poses two key challenges: (i) need for diverse expertise: animal experiments, analytical chemistry, and mathematical modeling; and (ii) multiple time and length scales involved, from enzymes and their reaction kinetics up to the level of tissue and animal physiology. The lab is unique in having the combination of mathematical and biological skills to successfully tackle these challenges.

CACHEXIA: Cachexia refers to the involuntary weight loss and tissue wasting associated with many diseases, including cancer, heart failure, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and infections. It is a strange metabolic phenomenon for an animal: eating less but burning more energy. What is the origin of this energy imbalance? How is wasting tissues physiologically good for the body? Why is supplementing energy nutrients not helpful? Is this imbalance due to the fact that the system is trying to balance something else (other than calories)? By making sense of this strange response by the host, we aim to reveal principles and mechanisms of energy metabolism of the body, and to develop disease treatment strategies. To study this phenomenon, we use established animal models of cancer cachexia.

OBESITY: Obesity is one of the most serious public health problems world wide. What we eat is an important determining factor: some foods tend to cause obesity while others do not. (E.g., high-fat diet is widely used in research to induce obesity in mice.) We want to ask these questions: what is it that makes a diet unhealthy (i.e., causing obesity)? Does the diet contain too little of some ingredients or too much of them? What are these key ingredients? Or is the “balancing” of different ingredients the key for a healthy diet? To answer these questions, we systematically vary the composition of the diet and quantify the fate of different nutrients in the animal body. We aim to reveal the strategies the body uses to deal with different foods and the mechanisms for implementing these strategies.

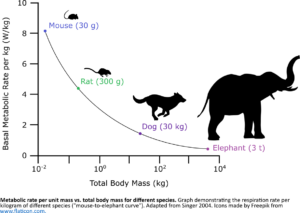

BODY WEIGHT DEPENDENCE OF METABOLIC RATE: A long-standing mystery in metabolism is that the basal metabolic rate (total energy expenditure at rest) of an animal scales sub-linearly with its body weight. Between mouse and human, the specific metabolic rate (metabolic rate divided by body weight) is 10 times higher in mouse. As energy fluxes are carried by enzymes in the energy production pathways, this body weight dependence implies a striking difference between animals of difference sizes: per unit mass of tissue, mouse contains 10-times more enzyme activity in the energy production pathways than human! How is this achieved at the molecular level? Do these energy production enzymes make up a larger fraction of the mouse proteome? If so, what proteins in the proteome get “squeezed”? Or are the human enzymes not efficiently utilized, functioning at 1/10 of their capacity. If so, what mechanisms control their efficiency? To answer these questions, we venture out into the area of in vivo comparative metabolism.

IN VIVO FLUX QUANTIFICATION: A key approach we take to probe mammalian metabolism is quantifying metabolic fluxes in vivo. This is done by administering isotopic labeled nutrients to the animal and then inferring fluxes from the isotopic labeling patterns of many metabolites. While this approach of isotopic tracing has been used since decades ago, recent breakthroughs in mass spectrometry, flux modeling algorithms, and animal surgical techniques promise revolutionary advancement in in vivo flux determination technology, which will not only be valuable for research but also for clinical purposes such as diagnosing diseases.