What scholars do know about the 1918 pandemic’s toll on the Black community raises more questions than it answers. According to a 2019 study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Black Americans—who might have been expected to suffer higher rates of infection and death during the vicious autumn wave—appear to have had lower overall morbidity and mortality than the white population, although African Americans who did become sick were more apt to die.

What explains this surprising finding?

A pathbreaking 2010 paper in Public Health Reports—authored by physician/historian Vanessa Northington Gamble, University Professor of Medical Humanities at George Washington University—tries to answer the question by looking at the broader picture of Black life and Black health in America. Gamble notes that the turn of the 20th century represented what one scholar called the “nadir in American race relations,” a period marked by disenfranchisement, anti-Black violence, legalized segregation, and white supremacist ideology.

During this time, African Americans suffered higher rates of illness and death from a number of diseases than did whites. The Atlanta Board of Health, for instance, reported in 1900 that the death rate in the Black population exceeded that in whites by 69 percent. In an analysis of the 1900 census, the sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois found that death rates for African Americans were two to three times higher than those for whites for several common afflictions, including tuberculosis, pneumonia, and diarrheal disease.

In his landmark 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro—the first sociological case study of a Black community in the U.S.—Du Bois summarized the situation succinctly: “The most difficult social problem in the matter of Negro health is the peculiar attitude of the nation toward the well-being of the race. There have … been few other cases in the history of civilized peoples where human suffering has been viewed with such peculiar indifference.”

“When the 1918 influenza epidemic began, African American communities were already beset by many public health, medical, and social problems, including racist theories of Black biological inferiority, racial barriers in medicine and public health, and poor health status,” Gamble wrote. Black physicians and nurses established their own groups of medical professionals, because they were barred from white professional organizations. They also established separate hospitals and other care networks to tend to their communities. When the pandemic raced across the country, it overwhelmed these separate, resource-poor facilities and home-based caregivers. And the injustice and indignity didn’t end with death: In Baltimore, for example, white sanitation workers refused to dig graves for Black flu victims.

Drawing on this context, Gamble offers several hypotheses for the apparently lower incidence of pandemic flu cases in Black communities. She suggests that African American deaths were probably underreported, because health departments simply didn’t keep good data on Black people. At the same time, she surmises that racial segregation in housing may have had a paradoxical protective effect on Black Americans, serving as a kind of de facto quarantine.

The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper from that era, observed the 1918 flu trends with indignation, as historian Elizabeth Schlabach recounted in a study published in 2019 in the Journal of African American History. Weeks after the deadliest day of the influenza outbreak in that city, the newspaper ran a story about the employment crisis at the Chicago Telephone Company: More than 300 white women were stricken—employees whom today we would call “essential workers.” “What we would like to know is whether or not this company is willing to accept applications from our girls, and if not, why not?” the Defender inquired. “The company is employing young women of every nationality on earth, French, German, Polish, Lithuanian, Irish and Swedish, the only test being that they must be white, apparently.”

IN HIS 1899 BOOK THE PHILADELPHIA NEGRO, THE SOCIOLOGIST AND CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST W.E.B. DU BOIS WROTE, “THE MOST DIFFICULT SOCIAL PROBLEM IN THE MATTER OF NEGRO HEALTH IS THE PECULIAR ATTITUDE OF THE NATION TOWARD THE WELL-BEING OF THE RACE. THERE HAVE … BEEN FEW OTHER CASES IN THE HISTORY OF CIVILIZED PEOPLES WHERE HUMAN SUFFERING HAS BEEN VIEWED WITH SUCH PECULIAR INDIFFERENCE.”

The plea fell on deaf ears. Under that era’s Jim Crow laws—state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation—Black people were barred from the coveted telephone jobs. As a Defender editorial observed, “The whole situation is ridiculous and could obtain in no other country except America. The disease is strictly Dementia Americana.”

African American nurses assigned to Camp Sherman Base Hospital, in Ohio, during World War I. Black physicians and nurses established their own groups of medical professionals during that era, because they were barred from white professional organizations. Photograph courtesy of Department of Special Collections and University Archives, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst

HISTORICAL ECHOES IN COVID-19

Today’s coronavirus pandemic is the only public health crisis in the last hundred years as profoundly disruptive to society as the 1918 flu. And like the 1918 pandemic, it has unmasked persistent racial injustice. According to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, one of the most reliable sources of data on racial disparities in today’s catastrophe, as of September 1, 2020, COVID-19 had killed at least 36,320 Black people in the U.S. A collaboration between the COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research, the Racial Data Tracker also found that while Black people make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 22 percent of deaths in which race is known. Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at 2.4 times the rate of white people.

Other studies confirm this skewed picture. Soon after the coronavirus pandemic took hold in the U.S., a Black-white gap emerged in cities and counties in the Carolinas, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Wisconsin. A working paper published in June by the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies looked at the outsized impact of the pandemic on premature mortality (death before age 65) in populations of color. The research showed that more years of potential life lost were experienced by Black non-Hispanic and Latinx populations than by white non-Hispanics, although the white non-Hispanic population is three to four times larger than either of the other groups.

A June report from the MIT Sloan School of Management, analyzing county-level data across the U.S., found that the higher the percentage of Black residents in a county, the higher its death rate from COVID-19—even after accounting for income, health insurance coverage, rates of diabetes, obesity, and smoking, and use of public transit. A county with a Black population exceeding 85 percent has death rates up to 10 times higher than a county with the lowest proportion of African Americans. For every 10-percentage-point increase in a county’s Black population, its COVID-19 mortality rate roughly doubles.

A study published in May by Nancy Krieger, professor of social epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and colleagues revealed that during the first two weeks of April, when COVID-19 infections were surging in Massachusetts, they soared far more in cities, towns, and ZIP code with high proportions of people of color, high levels of poverty, higher levels of crowded housing, and high “racialized socioeconomic segregation,” which takes into account both residential segregation and income and race/ethnicity. Indeed, the death rate was nearly 40 percent higher in places with the highest concentrations of low-income households of color, compared with places with the highest concentration of high-income white non-Hispanic households.

From the start of the pandemic, public health experts predicted this tidal wave of racial disparities. On March 2, when just 100 coronavirus cases were confirmed in the U.S., Mary Bassett, director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University and former commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and Natalia Linos, executive director of the FXB Center, published a prescient op-ed in the Washington Post. “Epidemics emerge along the fissures of our society, reflecting not only the biology of the infectious agent, but patterns of marginalization, exclusion and discrimination,” they wrote. “If this becomes a widespread outbreak,such an epidemic would probably be most devastating for the poorest Americans and for communities of color, who already are dying at younger ages and at higher rates from these common conditions.”

BLACK AMERICANS ARE MORE LIKELY TO BE EXPOSED TO THE CORONAVIRUS THROUGHOUT THEIR DAILY LIVES. THEY ARE MORE LIKELY TO WORK IN LOW-WAGE JOBS AND TO LIVE IN SEGREGATED, CROWDED NEIGHBORHOODS WITH HIGH RATES OF POVERTY, INCREASED POLLUTION, AND LIMITED TRANSPORTATION. THE BLACK COMMUNITY ALSO EXPERIENCES HIGHER RATES OF INCARCERATION AND HOMELESSNESS.

“It turned out to be true,” Bassett said ruefully in June. “I’m afraid this one has been a sorry fulfillment of earlier trends.” As health commissioner in New York City, Bassett had made racial justice a priority and worked to address the structural racism at the root of the city’s persistent gaps in health between its communities of color and its white communities. She knew exactly what minority groups were up against when COVID-19 arrived.

THE POWER OF SOCIAL DETERMINANTS IN HEALTH OUTCOMES

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and the social structures and economic systems that shape these conditions. These determinants explain almost everything about the racial disparities in risk, illness, and death that have unfolded throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Well before COVID-19, of course, racial disparities in health status were glaring. In the United States, the life expectancy for white females and white males is 81.2 years and 76.4 years, respectively; for Black females and males, it is 78.5 years and 71.9 years. According to the Office of Minority Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the death rate for Black people is higher than that of whites for “heart diseases, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, and homicide.” And when Black Americans become ill, they are more likely to receive inadequate medical treatment and to die from that neglect, according to the landmark 2003 report Unequal Treatment, published by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine).

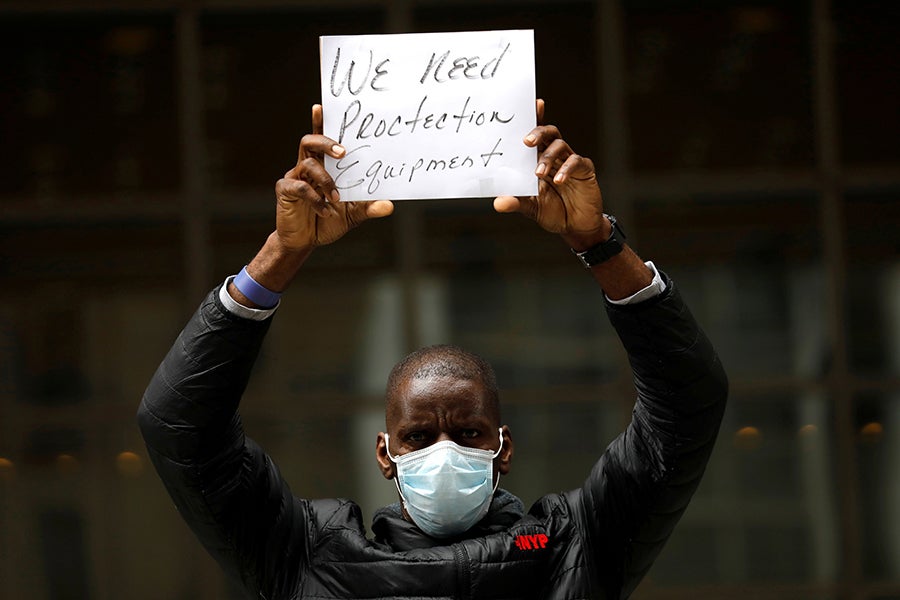

As COVID-19 swept across the country this spring, the social determinants that forge these health discrepancies and that fuel viral transmission became increasingly obvious. According to an April 2020 report in JAMA Health Forum, Black Americans are more likely to be exposed to the coronavirus throughout their daily lives. They are more likely to work in low-wage jobs and to live in segregated, crowded neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, increased pollution, and limited transportation. The Black community also experiences higher rates of incarceration and homelessness.

A 2018 report from the Pew Research Center found that among whites, 16 percent lived with multiple generations of family members; among Black people, 26 percent live in multigenerational homes—making it difficult to socially distance and to protect the elderly, who are more vulnerable to infection, from exposure. A March 2020 study from the Economics Policy Institute revealed that the ability to work from home—thus minimizing occupational exposure during the pandemic—varies dramatically by race and ethnicity. Nationally, 29.9 percent of whites can telework, compared with only 19.7 percent of Black people, who are disproportionately represented in essential jobs in transportation, government, health care, and food-supply services and in low-wage or temporary jobs. (For Hispanics, the work-from-home figure was even lower: 16.2 percent.)

Minority communities have lower levels of employment, home-ownership, and wealth than white communities—all critical financial bulwarks in weathering a drawn-out crisis like the coronavirus pandemic. In a 2018 analysis, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the poverty rate was 9 percent for whites, 19 percent for Hispanics, and 22 percent for Black Americans. A report published in February 2020 by the Brookings Institution found staggering racial disparities in wealth. At $171,000, the net worth of a typical white family in the United States was nearly 10 times that of a typical Black family ($17,150) in 2016, the most recent year for which data was available. The Brookings report also found that over the period between 2007 and 2013, which is during and after the 2007–2009 Great Recession—the most recent major economic downturn before today’s pandemic-triggered bust—the median net worth for white families declined 26.1 percent, while that for Black families dropped by 44.3 percent. Some experts suggest that, after COVID-19 recedes, the loss of wealth for Black families could, astoundingly, eclipse those earlier declines.

Using modern analytical methods, it is now possible to examine how social determinants magnified the effects of the 1918 flu pandemic. In a 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers parsing U.S. census-level data tied rates of illiteracy, homeownership, population density, and unemployment to survival. Although they did not look directly at race, the researchers did find that influenza and pneumonia deaths increased, on average, by 32.2 percent for every 10-percent increase in the illiteracy rate, when adjusted for population density, homeownership, unemployment, and age. As the authors concluded, with withering understatement, “Despite the highly virulent nature of the virus, influenza did not behave in a wholly democratizing fashion.”

In a report published in 2009 in the American Journal of Public Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clearly predicted the racial inequities salient in today’s coronavirus siege. Although written in bland bureaucratic language, the report accurately foretold how people of color would struggle under the weight of poverty, working conditions, housing environments, transportation options, and other inescapable facts of their lives during a future pandemic.

“What they wouldn’t have known then was that today’s pandemic was also going to play out in the midst of a federal administration that is both hostile to science and hostile to dealing with anything that has to do with inequity,” notes Krieger. “Even in a great administration that was concerned about public health, concerned about things like facts and truth, let alone concerned about equity, a pandemic would have been a hard thing.”

BLAME GAME

Pandemics can unleash anger and blame—often pointed in the wrong direction.

“There are long-standing interpretations that say the people who are to blame for these disparities are the people who experience them. Their bodies aren’t good enough. They don’t listen to instructions,” says Bassett. “This has been the prevailing mantra. Although people give lip service to the social determinants of disease, they put those determinants in some outer stratosphere that we need to mention, while the things that many public health people consider action-oriented steps are health communications and better medical treatment. Those interventions aren’t wrong, but the first step in dying of COVID is getting infected with it. And we have had many, many patients who simply were not in the position to protect themselves from infection.”

Clyde W. Yancy, a physician at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, offered a similar critique in an article published in May in JAMA: “What makes this particularly egregious is that unlike the known risk factors for which physicians and others can stridently offer clear advice regarding prevention, these concerns—the burden of ill health, limited access to healthy food, housing density, the need to work or else, the inability to practice social distancing—cannot be well articulated as clear, pithy, and easily actionable items.”

In April, journalist Linda Villarosa, a 1991 fellow at the Harvard Chan School’s Center for Health Communication, published a powerful cover story in the New York Times Magazine, “‘A Terrible Price’: The Deadly Racial Disparities of Covid-19 in America.” Delving deeply into national history and into the proud Black culture of New Orleans, the article dismantled the victim blaming that arose when the pandemic first hit. Blaming African Americans for their susceptibility to COVID-19, Villarosa said in an interview in June, “plays into the stereotype that something is wrong with Black people. Something is wrong with you. You’re not taking care of yourself. You are not paying attention to your health because you don’t care. I’m saying, let’s get away from that narrative.”

NO DATA, NO PROBLEM.

One way to shift the conversation is to rigorously gather data about health disparities and mandate through laws or regulations that this data be made public. Gathering such statistics, after all, is a core function of public health. As Krieger says, “It’s an age-old adage: No data, no problem.”

Early data from the CDC was full of holes, making it impossible to gauge the impact of the pandemic on people of color. “Without demographic data on the race and ethnicity of patients … it will be impossible for practitioners and policymakers to address disparities in health outcomes and inequities in access to testing and treatment as they emerge,” Democratic lawmakers wrote to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in March. “This lack of information will exacerbate existing health disparities and result in the loss of lives in vulnerable communities.”

This spring, a coalition of national, state, and local organizations focused on health, racial equity, and civil rights launched a project called We Must Count. The name is a scathing triple play on words: an assertion of group identity, a call for recognition, a demand for action. The coalition hopes to compel governments at all levels to track and report on COVID-19 testing, cases, health outcomes, and mortality rates using data disaggregated by race, ethnicity, primary language, genders, disability status, and socioeconomic status.

The Harvard Chan School’s Krieger, who over the past three decades established many of the theoretical constructs for studying inequities in health across populations, also pioneered the methods by which census tract and ZIP code can be used to uncover disparities at fine-grained geographical levels. Given the tragic scope of today’s pandemic, Krieger takes no personal satisfaction in the fact that her health-monitoring tools have proven critical in understanding the human cost of COVID-19. “What I am glad for is that our tools are useful,” she says. “But I’m so angry and anguished and outraged.”

ANOTHER BLOW: THE KILLING OF GEORGE FLOYD

In May, during the first deadly wave of COVID-19, a Black man named George Floyd was arrested for a minor offense in Minneapolis and restrained for more than eight minutes by a white officer’s knee to the neck, killing Floyd. When a cell-phone video of Floyd’s death went viral, it set off protests across the United States and in many countries worldwide.

The horror seemed of a piece with COVID-19’s disproportionate strike on the Black community. Floyd’s death and the rampage of COVID-19 pulled the same historical thread: the endless repercussions of the institution of slavery on which the U.S. was founded. It also generated political echoes from 1918—a previous juncture of public health calamity and progressive political organizing.

“PEOPLE ARE REDISCOVERING HISTORY AND REALIZING THAT THEY HAVE TO UNDERSTAND THE HISTORICAL CONNECTIONS TO UNDERSTAND HOW WE GOT AS A COUNTRY TO WHERE WE ARE NOW. IT ALSO SPEAKS TO THE POSSIBILITIES FOR CHANGE.” —NANCY KRIEGER, PROFESSOR OF SOCIAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

“There are a lot of interesting parallels between today and what happened with regard to the 1918 pandemic,” says Krieger, “including what happened when the pandemic entered a society where there were all these different social justice movements at play—and also serious crackdowns on those who were trying to stand up for a different kind of economic system that was more inclusive.” Krieger notes that the time of the 1918 flu pandemic was also a period of major raids on any activism in the United States that was considered left wing. “Remember, the Bolshevik Revolution happened in 1917,” she says. “There was the Red Scare in the U.S. in 1918 and 1919. There was organizing around multiple issues, and one of the organizing groups that became active at that time, the International Workers of the World, or IWW, was one of the very few that actually had interracial organizing. Those are instructive parallels to look at. People are rediscovering history and realizing that they have to understand the historical connections to under-stand how we got as a country to where we are now. It also speaks to the possibilities for change.”

TRUTH-TELLING COLLABORATIONS

In this roiling time, people are eager to understand the roots of racism and its effects on the health of individuals and communities. According to Villarosa, “Right now, there’s a hunger for more information and a greater understanding. And right now may be the pinnacle of it, because there’s the combination of people having more time to consume a longer story—because we’re locked inside—and people really grappling with issues of race and justice and inequality and disparities.”

Much of this wider context has been supplied by new collaborations among journalists and public health researchers. The first data sets to document numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths by U.S. county, released on March 27, were produced not by a government agency but by the New York Times and Washington Post. To analyze exquisitely local COVID-19 data in Massachusetts, Krieger established a fruitful partnership between her scientific team and the Boston Globe.

“Frankly, in the case of the United States, it has been investigative journalists who have gotten most of the best data and have been doing the best data visualizations and the best stories—far outstripping any health department,” Krieger says. “Between the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Globe, the Guardian, the New Yorker, it’s like the institutions of journalism have turned into public health journals. It’s quite striking.”

Villarosa agrees. “Part of the change is that we have better tools for visualizing data, which has made epidemiology and biostatistics more interesting to journalists, because we can work with data using tools that were less available. And journalists have been forced to have a better and deeper understanding of public health, because we’re dealing with a public health crisis.”

She adds: “Now is also a time when the administration and the White House are trying to erode trust in journalism. These journalistic partnerships with science are extremely helpful to get out a textured sort of truth telling—a truth telling that journalists know how to do. We know how to tell stories. We know how to weave and craft narratives. When that skill is married with hard information—rock-solid, historical, and evidence-based—it’s a perfect collaboration.”

As Krieger sees it, “There are two kinds of stories that are happening. There are the stories that people tell with their bodies, as interpreted by epidemiologists. And there are the stories that are interpreted by journalists. Together, they’re powerful.”

“A MOMENT OF ETHICAL RECKONING”

The 1918 flu pandemic and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic are both prisms on racial injustice—the “Dementia Americana” that the Chicago Defender diagnosed more than a century ago.

“When you have a public health crisis, an infectious disease that is sickening and killing people, it brings out in some ways the best of people—those who are health care providers, those who care for one another—but also the worst, because there’s so much fear,” says Villarosa, whose book Under the Skin: Race, Inequality and the Health of a Nation will be published in fall 2021. “It also brings out the underlying racist ideology that’s floating around. When people are tired, afraid, panicked, and looking to blame someone, these ideas come out.

“THERE ARE LONG-STANDING INTERPRETATIONS THAT SAY THE PEOPLE WHO ARE TO BLAME FOR THESE DISPARITIES ARE THE PEOPLE WHO EXPERIENCE THEM. THEIR BODIES AREN’T GOOD ENOUGH. THEY DON’T LISTEN TO INSTRUCTIONS. THIS HAS BEEN THE PREVAILING MANTRA.” —MARY BASSETT, DIRECTOR OF THE FRANÇOIS-XAVIER BAGNOUD (FXB) CENTER FOR HEALTH AND HUMAN RIGHTS

That was as true in 1918 as it is today, she says. “At the time of the 1918 pandemic, Black people were at the breaking point, a crisis point—newly freed but still facing disenfranchisement, anti-Black violence, including lynchings—and they were still legally segregated. There was racism in health care. And there were long-standing racist ideas that some-thing is wrong physiologically with the Black body, and that something is wrong mentally, emotionally, and morally with Black people in general. Black communities were segregated, unclean, left to falter from our society in a state-sanctioned way that brought on disease and lowered life expectancy.”

As Northwestern’s Yancy wrote in JAMA, “This is a moment of ethical reckoning.”

But will the moment bring the needed reckoning? At the end of May, New York Times columnist Roxane Gay wrote: “Eventually, doctors will find a coronavirus vaccine, but Black people will continue to wait, despite the futility of hope, for a cure for racism.”

“My own sense is that the COVID pandemic by itself would not have occasioned such a strong response—that people would havjust shrugged their shoulders and said health inequities are inevitable, blaming them on preexisting conditions as opposed to framing them as preexisting inequities,” says Krieger. “And had the George Floyd killing not happened during the pandemic, had it not happened after a period of shutdown and economic distress, it also may not have had the same effect. But the COVID pandemic plus the gross injustice of the brutal murder of George Floyd, filmed with the offending officer looking completely indifferent— both struck the same nerve.”

And that rare confluence of public tragedies could be pivotal. “We’re at the point now where we have to jump past the business of trying to put each other at ease and actually have the conversation,” said former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, in a Harvard Chan School Voices in Leadership discussion in July. “That means, on the part of a lot of people, putting your defenses down, opening your heart, and listening.”

“I wasn’t part of the civil rights movement, so in my lifetime, this is the biggest moment of reckoning that I’ve seen,” says Villarosa, who is 61. “It is a clarion call. It is a time for change. And I see an openness that I’ve never seen in my lifetime for a radical upheaval leading to revolutionary change. I see it in a hunger for information from young people. I see it in a hunger in white people to understand the racial disparities and not blame individual Black people for the issues that we face.”

Evelynn Hammonds sounds a note of caution. “Whenever there are these kinds of moments in American history, there’s always backlash. There’s resistance. And I think we’re going to see more of that.” To leverage this historical moment with the aim of eliminating racism once and for all, Hammonds believes that data is not enough. “We can’t just create more and more complex models,” she says. “We can’t just keep drawing maps and showing them to people. We have to look at the structures that support the social determinants of health and figure out how those structures can be dismantled.”

Mary Bassett agrees, in part. “Moments can turn into movements, and they can fail. I as a young person was part of the radical health movement, which framed health as a human right. I’ve seen movements fail. People often think they fail because activists got tired or decided that they had to make more money or something like that. But the reason they fail is more accurately a combination of pushback, of employment opportunities lost, of leadership arrested, of leaders being killed,” she says. “It’s possible that this moment could end with words, and like the Occupy Wall Street action, leave us with a sense that there was a moment, but that the moment didn’t turn into a movement.”

Yet even Bassett senses there is something new afoot. “I may be overly optimistic, but I haven’t seen this kind of outpouring of wide-spread public protest in 50 years, seemingly spontaneous. The thing that is transformational is the embrace by young people who are not people of color. Corporations are saying that they have to support the movement. We’re witnessing some-thing that could be a tipping point, and it makes me incredibly hopeful. Things that were considered too fringe to talk about, raised by people from unexpected quarters, using phrases like ‘white supremacy’ or the concept that reparations should be treated with seriousness—these things matter,” she says. “Efforts in the past have failed. But the things that drive people and motivate them to stand and fight, they’re still here.”

Madeline Drexler is editor of Harvard Public Health

Lead image: The National Library of Medicine / Public Domain