As executive director of the Innocence Project, Madeline deLone works to free wrongfully convicted people from prison using DNA evidence.

Calvin Johnson almost didn’t make it out. Imprisoned for life in Georgia for a rape he did not commit, he is a free man only because of a chance discovery. A summer intern walking through a parking lot at the back of the Clayton County district attorney’s office happened to notice a box marked “Evidence” and wondered why it was next to the trash. The box included the “lost” evidence that Johnson and his legal team at the Innocence Project had been seeking for many years. Johnson spent 16 years in prison before being exonerated based on that DNA evidence.

Marvin Anderson, sentenced to 210 years in prison in Virginia for a rape he did not commit, was freed only because a crime lab analyst—contrary to policy—had saved some of the physical evidence from the case instead of destroying it. Nineteen years later, when the evidence was discovered and tested, DNA analysis excluded Anderson as the perpetrator. He had spent 15 years in prison and four years on parole fighting, alongside the Innocence Project, to have his conviction overturned.

Johnson and Anderson are two of the lucky ones—the 333 wrongfully convicted individuals who have been exonerated in this country through DNA evidence. The Innocence Project represented defendants or provided significant assistance in 177 of these cases.

Since 2004, Madeline deLone, AB ’81, SM ’84, has been executive director of the Innocence Project, which includes a team of lawyers and law students who work pro bono to free innocent people from prison using DNA evidence. Her particular focus is people “deprived of their liberty and freedom,” as she phrases it in her lawyerly way—and especially those unjustly imprisoned.

Her passion for the job, you might say, is in her DNA. DeLone comes from a long line of Philadelphia Quakers committed to social justice. Her great-great-grandmother was a suffragette who tied herself to the White House fence and went on a hunger strike for women’s right to vote. Her grandmother insisted that people leave her house if they used racial epithets. Her parents worked in education. “In my family, there was a strong sense that every human being was valuable and important,” says deLone, “and it was the job of people who had much to give much back to others.”

PRISON AS A PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

The United States, with just 4.4 percent of the world’s population, houses 22 percent of the global prison population.

It also has the highest per capita prisoner rate in the world, at 716 per 100,000 people, or some 2.2 million individuals behind bars. Mandatory minimum sentences, the criminalization of many behaviors, “three strikes and you’re out” statutes—these and other policies enacted in the 1970s and ’80s have caused prison populations to swell by 700 percent over the last 40 years.

Before she worked in the criminal justice system, it had never occurred to deLone that a significant number of people who were serving time were innocent. Calvin Johnson, Marvin Anderson, and the others freed since 1989 with the help of the Innocence Project represent just the tip of the iceberg of wrongfully convicted people. If, as conservative estimates suggest, 1 percent of people in prison in the United States are innocent, that would mean that 22,000 people are behind bars for crimes they did not commit. Many experts think the percentage is realistically more like 2.5 to 5 percent—meaning that some 55,000 to 110,000 wrongfully convicted people are serving time.

The fallout hurts not only individuals but communities as well. “Mass incarceration is one of the great public health challenges of our times,” notes the Vera Institute of Justice in a 2014 report titled On Life Support: Public Health in the Age of Mass Incarceration. The millions of people who cycle through the nation’s courts, jails, and prisons experience chronic health conditions, infectious diseases, substance use, and mental illness at much higher rates than the general population. Large-scale imprisonment, the report further notes, “has stretched the social and economic fabric of communities, contributing to diminished educational opportunities, fractured family structures, stagnated economic mobility, limited housing options, restricted access to essential social entitlements, and reduced neighborhood cohesiveness. In turn, these collateral consequences have widened the gap in health outcomes along racial and socioeconomic gradients.”

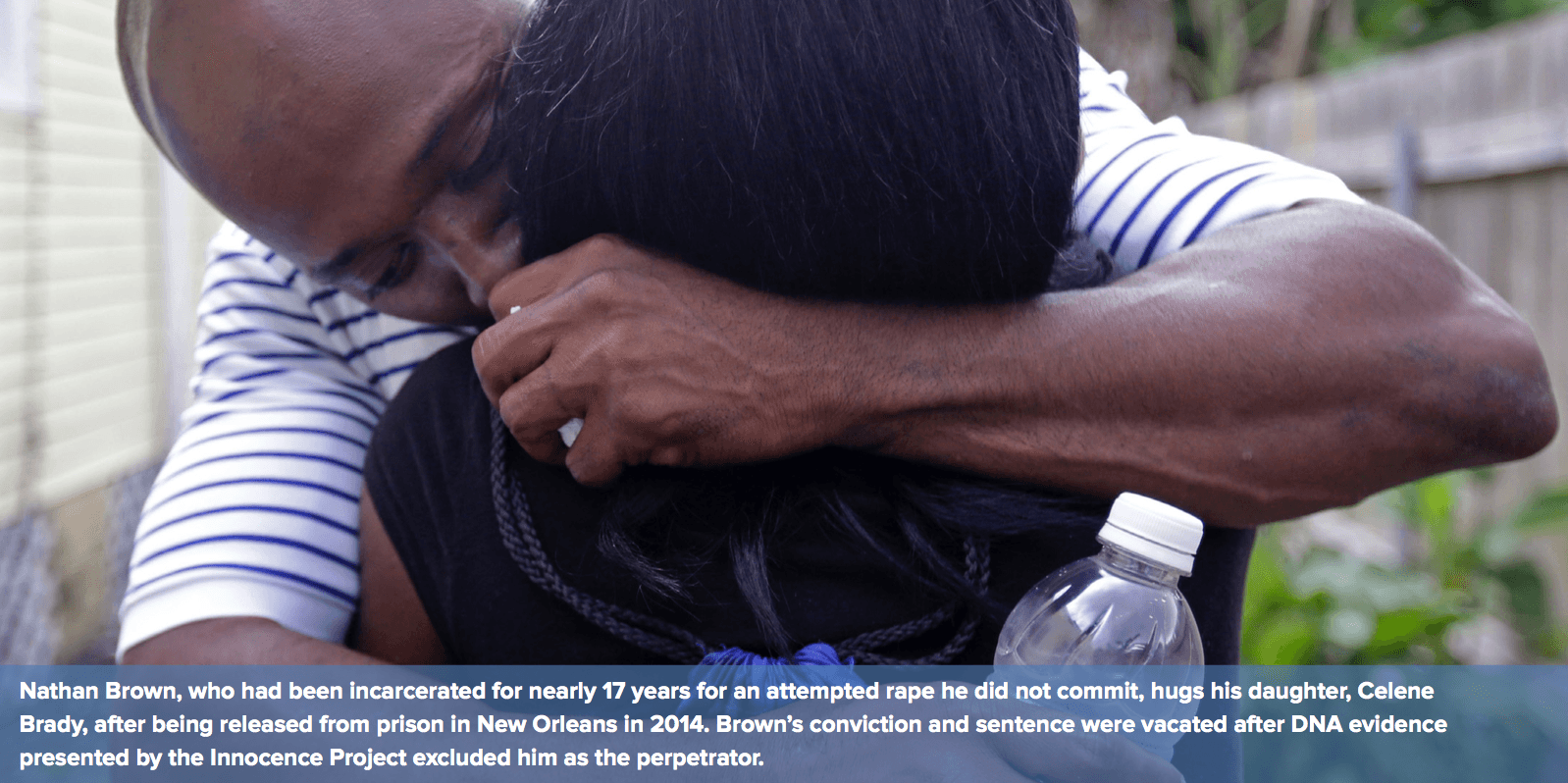

The personal costs are largely hidden. One mother never celebrated birthdays or holidays during the 20 years her son was in prison before being exonerated; there was nothing to celebrate, she explained. Some families spend enormous resources trying to stay in contact with their loved ones, who often are assigned to facilities far from the family’s home. Sometimes families aren’t able to continue visits over decades, and loved ones drift apart. Children, especially, can feel aban- doned. When people are released from prison, the rebuilding and healing can take years—or never happens at all.

The scenarios are all the more tragic when a person has been imprisoned for a crime he or she did not commit.

PROVING INNOCENCE: A FORMIDABLE CHALLENGE

Proving one’s innocence while behind bars is daunting. One of the surest ways is to present DNA evidence that was not considered at the trial. But, says deLone, in more than 90 percent of cases of serious violent crime—for example, drive-by shootings—no DNA evidence exists. Cases in which the perpetrator’s DNA is often present are those involving rape or murder. The effort to track down this evidence and proceed through myriad legal motions is painstaking and can go on for years. Sometimes evidence has been lost or destroyed, and an innocent person is never exonerated. The Innocence Project closes nearly 25 percent of the cases it takes on because the exculpatory genetic evidence is never found.

“Whenever we get someone out of prison, I think about how old they were when they went in and how old they are now,” deLone says. “And I may compare that to my own family. Some people didn’t get out until they were 30, but they were imprisoned when they were 17—at that time, about the same age of my kids. Or they went to prison in 1981, when I got out of college, and they are just coming out now.”

These empathic calculations sustain her. “Every time someone gets out,” says deLone, “no matter how hard the work seems or how frustrating some of the battles are, I can’t imagine anything more important than helping the next person get out and preventing the next person from going in.”

“THE ONLY STUDENT CRAZY ENOUGH FOR THIS JOB”

DeLone found her way to prison work through two Harvard schools. After studying biological anthropology at Harvard/ Radcliffe colleges and planning to be a doctor, she shifted her focus and came to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where she studied health policy and management. Courses on the epidemiology of mental illness led her to start thinking about people who were institutionalized, whether through psychiatric hospitalization or criminal incarceration.

She worked most closely with health systems expert Marc Roberts, professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management, who passed away in 2014. Knowing of her work with Roxbury Youthworks, which helped young people in the inner city through alternatives to incarceration, Roberts informed her of a job in the Department of Juvenile Justice in New York City, overseeing health care for kids in juvenile detention. “He said I was the only student he’d ever met who was crazy enough to think that this would be a good job,” she remembers. “It was not a time when many people in public health were focusing on criminal justice. But I thought it sounded like the most interesting and important job imaginable.”

After working with incarcerated adolescents, deLone went on to become the administrator of a 24-hour clinic in one of the jails on Rikers Island in New York that housed 2,500 men. A year and a half later, however, the anger and fear that pervaded the jail environment every day wore her down, and she left to continue work on prison health improvement from outside the jails. Eventually, deLone went to law school, becoming first a litigator for children’s rights, and later working as a staff attorney at the New York Legal Aid Society’s Prisoners’ Rights Project.

Then she heard about the Innocence Project, a young nonprofit that needed a leader to help it grow. She was already a believer. “When we as a society lock people up, we have an obligation to try to minimize the harm that comes from that act,” she says. “It’s even more critical to take a person out of that situation who has actually done nothing wrong.”

A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH TO PRISON REFORM

Drawing on her Harvard Chan experience, deLone has adopted a public health approach to both improve life for prisoners and prevent innocent people from being incarcerated in the first place. Volunteering for years on the prison health committee of the American Public Health Association, she edited the third edition of the association’s Standards for Health Services in Correctional Institutions. Determined to weave international human rights principles into the updated standards, she and the committee pored over treaties, conventions, and other international docu- ments and standards to see how they could be applied to U.S. prisons, particularly to address issues raised by prison violence and solitary confinement.

More recently, in her leadership role at the Innocence Project, she has sought to bring the rigor of public health research techniques to forensic science, which in many ways remains unvalidated. While fingerprint evidence might seem irrefutable, for example, there are some cases of innocent people being convicted in which faulty fingerprint evidence contributed to a wrongful conviction. Juries unaware of the dearth of scientific backing behind many forensic disciplines may believe shaky evidence to be fact, increasing the likelihood of wrongful convictions. DeLone believes that public health epidemiologists and biostatisticians can help improve forensic science in the criminal justice system by strength- ening study design and analyses, and that others in the public health community can work with those in the criminal justice system to help apply principles of quality improvement and learning from error to the field.

FIRST DAY OF FREEDOM

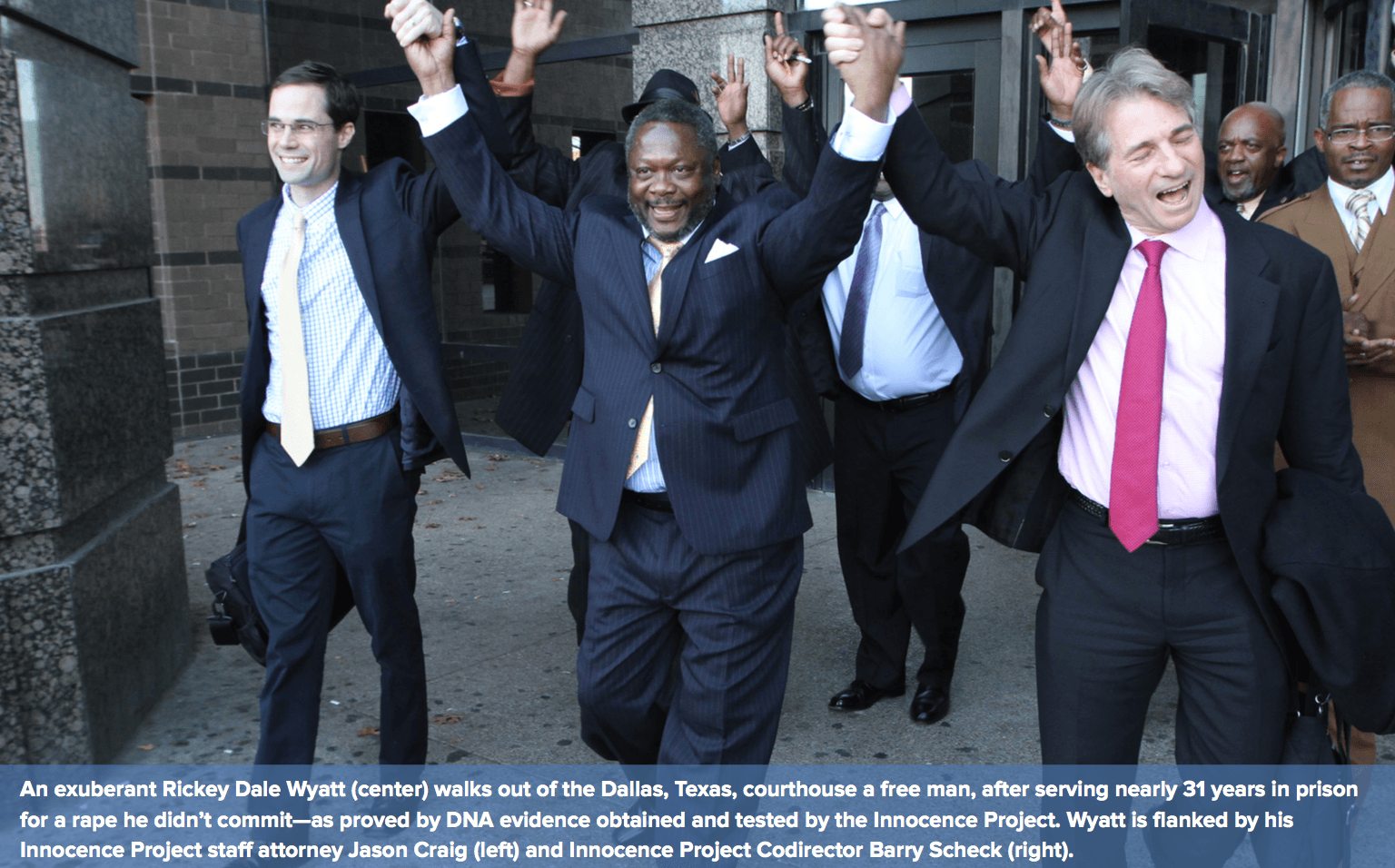

After losing years or decades to wrongful incarceration, exonerees emerge into a world that’s utterly changed. Although justifiably angry when first imprisoned, at some point, observes deLone, many come to some sort of peace with the situation, refusing to permit anger to eat them from the inside.

Indeed, by the time of their release, most exonerated individuals have forgiven the people involved in their imprisonment—even those whose mistaken eyewitness identification ensured their conviction—and just want to get on with their lives. Frequently, they are driven to make sure that what happened to them doesn’t happen to anyone else. “They become tremendous advocates for the reforms that will prevent wrongful convictions,” says deLone. “There is no more powerful voice than the voice of the exonerated.”

As joyful as it is, however, an exoneree’s release can also be bittersweet. “There’s something amazing and wonderful about welcoming someone home, and at the same time something unbelievably horrible about the error and the amount of time they spent away,” says deLone. She worries about the wrongfully convicted people who don’t have that sustaining inner strength, the people the Innocence Project may never find because they have given up.

Upon each prisoner’s release, the Innocence Project team sets up a videoconference with the exoneree, who is usually accompanied by an Innocence Project lawyer and social worker and often the law student who most recently worked on the case. “When the exoneree calls in,” says deLone, “the room bursts into applause, and it goes on for as long as people can clap. You think somehow you would get used to it. I’ve probably been here for 75 or 80 of these exon- erations and peripherally involved in a number more, and it never gets old. It takes my breath away every time.”

Jan Reiss is assistant director of development communications and marketing at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.