Government-funded program known as PEPFAR allowed School to scale up efforts

February 11, 2013 — The largest public health initiative in history dedicated to a single disease was announced unexpectedly during President George W. Bush’s State of the Union address in 2003: $15 billion over five years to fund a new international AIDS effort. For AIDS researchers at HSPH, the program known as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) offered the opportunity to dramatically scale up their efforts in African countries hit hard by the disease.

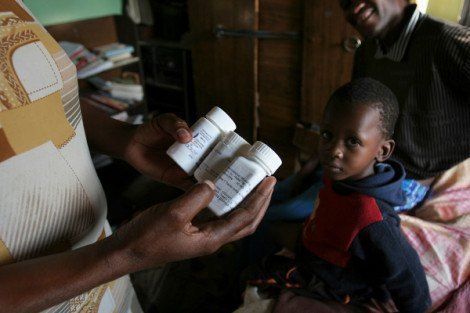

“By the early 2000s, thanks to new drug discoveries, AIDS was no longer a death sentence in the developed world. But the vast majority of AIDS patients, who were (and still are) in Africa and Asia, didn’t have access to treatment,” said Phyllis Kanki, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at HSPH. Kanki spearheaded the School’s application to PEPFAR— the largest government grant in Harvard University’s history. “PEPFAR was designed to address that gap. We couldn’t really go on thinking that we had addressed the AIDS epidemic if we didn’t do something to provide treatment to people in resource-limited countries.”

The School received a total of $362 million from PEPFAR for work in Nigeria, Botswana, and Tanzania training health care workers, developing monitoring and evaluation systems, strengthening health care infrastructures, and collaborating with local hospitals and clinics that provide treatment for AIDS patients. HSPH’s PEPFAR grants wound down last year, and researchers at the School are now working with partner organizations to transition activities to full local ownership.

The legacy of Harvard’s PEPFAR program is immense: newly refurbished and equipped clinics and labs, thousands of trained health care workers, and the treatment of more than 160,000 people who otherwise would not have received lifesaving AIDS drugs.

“PEPFAR has demonstrated that with the appropriate resources, we can support the highest quality of care with the local economy in mind. Outcomes have been great,” said Kanki, who has served as the program’s principal investigator, devoting most of her time to the Nigeria program. Richard Marlink, Bruce A. Beal, Robert L. Beal, and Alexander S. Beal Professor of the Practice of Public Health, directed efforts in Botswana, and Wafaie Fawzi, professor and chair of the Department of Global Health and Population, oversaw the program in Tanzania.

“By all accounts, PEPFAR has been quite successful,” Max Essex, Mary Woodard Lasker Professor of Health Sciences and chairman of HAI said at a January 10, 2013 symposium. “This is in no small part because of Harvard School of Public Health’s efforts.”

A partnership approach

From the beginning, HSPH researchers involved in PEPFAR adopted the partnership approach used by HAI in the countries that host its programs, Marlink said. “Any work we do has to help the health of the people who live in that country. We’re not in charge even though we’re coming in with money. Our hosts have to decide how best to use it.”

Infusing PEPFAR’s massive budget — and the stringent rules that came with it — into the system demanded quick decisions on a huge range of issues. Most international projects can be run as sub-contracts out of a faculty member’s research budget, Marlink said, but PEPFAR was so large and complex it required the creation of a new administrative entity in each country that would allow the initiatives to continue beyond the initial funding. From human resources policies to governance structure, everything had to be built from the ground up.

The experience has provided a wealth of insights that can be applied to future large-scale public health efforts, Fawzi said. “It was important for us from the start to have an operations research agenda. We were keen to develop lessons that could be replicated and shared.” (see sidebar)

Lessons learned

Source: Harvard School of Public Health PEPFAR PEPFAR’s global impact

Source: www.pepfar.gov |

Health benefits extend beyond one disease

A key lesson the researchers learned is that efforts focused on a particular disease can have a beneficial ripple effect throughout the rest of a country’s health care system.

“The labs we renovated weren’t only for HIV tests,” Marlink said. Their expanded capacity enabled more tests to be conducted for a range of other conditions such as tuberculosis and other chronic diseases. And health care workers were trained to address the whole of their patients’ lives, not just their HIV status. “They started asking their patients about issues like their family situation and whether they had access to clean water. That helps do more than prevent HIV infection. That helps the health of the entire population.”

The researchers and their colleagues will continue to be involved with the programs in various capacities, such as serving as advisors, technical assistance projects and training programs. And they eagerly await word on whether the U.S. Congress will reauthorize PEPFAR later this year, allowing the now-independent Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, AIDS Prevention Initiative in Nigeria, and Management and Development for Health (Tanzania) to apply for additional funding.

“Care needs to be sustained,” Fawzi said. “We still have a long way to go.” The governments of some of the countries receiving PEPFAR funding may be able to fill the gap if the program is not reauthorized, but poorer countries like Tanzania are likely to lose the progress they have made against HIV/AIDS over the past decade.

Marlink is optimistic. “Those of us who have seen the use of these funds realize that they are a good investment in saving lives and preventing new HIV infections,” he said.

PEPFAR should not only be continued but could also be used as a model for tackling other treatable infectious diseases like tuberculosis and malaria, and chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, Marlink said.

At the recent PEPFAR symposium, HSPH Dean Julio Frenk observed, “PEPFAR changed the way we think about what public health can accomplish.”

Kanki observed, “Everyone was surprised by what we were able to do. In the grant application, we said that we would get 100,000 people on treatment in Nigeria. That amount seemed astronomical at the time, but we hit those numbers and beyond.”

Read Harvard Magazine coverage of the symposium

Read Harvard Gazette coverage of the symposium

HSPH delegation visits Tanzania and Botswana nutrition, AIDS program

HSPH Professor Fawzi expands HIV/AIDS collaborations in Tanzania