October 15, 2020 – The trillions of cells that make up our body are typically stationary. They stay at a fixed location, tightly attached to neighboring cells by so-called “adhesion molecules,” a sort of biological superglue. On certain occasions, however, a cell can break free of its adhesion molecules and detach from its neighboring cells. It then turns on its propulsive motor and cruises off to points distant. Scientists call this process the “epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition,” or simply the EMT. The EMT is beneficial for biological processes such as tissue growth and organ formation. However, the EMT can also be detrimental, for example, when a cancer cell invades surrounding tissues.

Since its discovery in the 1980s, the EMT has been thought to be the only way for a cell comprising tissue to acquire migratory capacity. Known exceptions do exist whereby cells can migrate collectively, but these cases have remained poorly understood and have often been attributed to partial EMT.

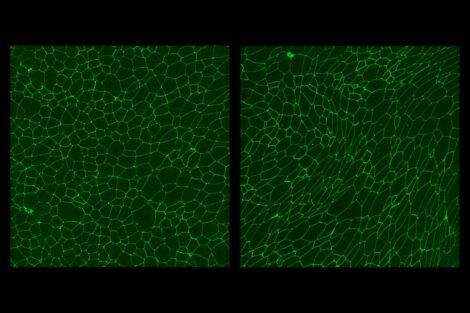

Researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have discovered an altogether different biological program through which cells acquire migratory capacity. It is called the unjamming transition, or UJT. Rather than degrading cell-cell contacts, delaminating from the tissue of origin, and finally scattering as individual entities as they do after EMT, cells instead maintain cell-cell contacts, remain integrated within the tissue of origin, and migrate collectively after UJT.

The research team noted that the UJT might be a fundamental mechanism for collective cellular migration during embryonic development, tissues regeneration, and cancer metastasis. For example, it had been thought that cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis cannot occur without EMT. But the new findings suggest other possibilities for how metastasis occurs and could eventually help researchers develop better and more targeted cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

“This study establishes the UJT as a newly discovered pathway by which cells become migratory, distinct from the well-studied EMT,” said Jin-Ah Park, assistant professor of airway biology and corresponding author of the study. “If comprehensive understanding of the UJT is accomplished in the future, we might then be able to develop a strategy for promoting or stopping cellular migration.”

The study was published in Nature Communications. Other Harvard Chan School authors included Jennifer Mitchel, Michael O’Sullivan, Ian Stancil, Stephen DeCamp, Stephan Koehler, James Butler, and Jeffrey Fredberg. Researchers from Northeastern University and Instituto de Neurociencias in Spain also contributed to the study.

Read the Nature Communications study: In primary airway epithelial cells, the unjamming transition is distinct from the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

images courtesy of Jennifer Mitchel and Jin-Ah Park