[ Spring 2014 ]

With a mixture of research, persuasion, and social media moxie, Ashish Jha seeks to drive health care improvements

Several years ago, Ashish Jha got the call that middle-aged children dread. His mother was on the phone from New Jersey. His basically healthy 74-year-old father was confused and unresponsive, obviously ill, and needed to go to…

“Probably the most dangerous place in the world for a human being: an American hospital,” says the Harvard School of Public Health professor of health policy and management. “Nothing we do in our lives puts us at such great risk for injury as being a patient in a hospital. Not driving. Not flying. Not even being a pedestrian in Boston. Nothing else is close.”

That’s surprisingly strong stuff from someone known for his unbiased, play-it straight approach to research, whose data-dense articles are published in upper-echelon medical and health policy journals, and who is an increasingly influential member of the Washington health care wonkerati.

But it’s not the least surprising when you know that Jha, MPH ’04, is a social media natural with a witty Twitter feed and a well-read blog, that he wants to shake up the incentives in health care so it becomes safer and less costly (one proposal: tying hospital CEO pay to patient safety outcomes), and that prowling within a disarmingly sunny, friendly personality is impatience, bordering on outrage, at the snail’s-pace rate of change in health care: “There are real human costs to taking an incremental approach to health care safety. Tens of thousands of people—tens of thousands—die needlessly each year because we are not moving fast enough.”

ACA not a panacea

Some contend that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will put the foot on the accelerator. Jha disagrees. He was happy that the Supreme Court upheld the law, describing it as the most important health policy innovation in the world today. “It’s a good first draft, but nobody’s first draft is perfect. I wish we could rewrite parts of it.”

The main thrust of the ACA is expanding health insurance. But as Jha points out, “Health insurance gives you more access to health care—but health care isn’t health.” A study of Medicaid coverage in Oregon conducted by his colleague Katherine Baicker, PhD ’98, HSPH professor of health economics, showed that while such coverage did improve mental well-being and financial security, it did not improve many key measures of physical health.

The reason, Jha says, is that the law doesn’t do enough to improve the quality of health care that it’s helping pay for. Improved quality consists not only of reducing the number of errors, but also of remedying the acts of omission: the preventive services that aren’t delivered properly or the evidence-based treatments that aren’t followed. “The big things that cause morbidity and mortality and suffering—things like heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, chronic diseases—our system is just not very good at managing them.” While the ACA makes minor improvements in those areas, in Jha’s view they’re weak medicine for a serious problem.

Stronger medicine, says Jha, would be major changes to the way health care is paid for, which he contends has only been tinkered with over the past 50 years, and in a way that largely turns a blind eye to safety and outcomes. “If a hospital takes care of heart attack patients and kills them at twice the rate of another hospital, it gets paid about the same amount. That doesn’t seem quite right.”

Bihar to Boston

Jha was born in the northeastern India state of Bihar, one of the poorest regions in the country, and lived there till he was 9, when his parents, both educators, emigrated to Toronto. When he was 14, the family moved to Morris County, New Jersey. Jha thrived—a gifted math and science student, editor of the high school newspaper. He had the motivation that comes with being the child of immigrants. “The way you become accepted is through demonstrable achievement. You have to be able to show that you are good, that you are worthy, that you belong.”

After graduating from Columbia University as an economics major, he applied to medical schools for the reason you can’t mention on applications: to please his parents. They desperately wanted one of their two children to become a physician; his older brother was emphatically not interested. Jha went into internal medicine because “as an internist, your specialty is the patient, not an organ or a disease.” He still practices, working as a hospitalist in two-week rotations about six times a year at the VA Medical Center in West Roxbury.

It was near the end of his residency that Jha had the insight that steered him to a career in public health. The shortcomings, the frustrations, and the mistakes he was making happened not because he wasn’t smart enough or working hard enough, but because of the health care system itself. “If the goal was to be as good a doctor as I could be, the only way was to work in a better system.” He went on to a two-year program that combines a general medicine fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an MPH at HSPH.

Today’s physicians and nurses, he explains, are better trained and equipped than ever before. But with all that capability comes complexity—and an exponential growth in the chances for things to go wrong. Jha argues that the focus needs to be on fixing systems. “Investing in improvement is no longer about telling doctors and nurses to do the right thing. It’s about fundamentally redesigning how you take care of patients.”

Raising the stakes

Jha has a convert’s zeal and conviction when it comes to revelatory powers of data. His blog is called An Ounce of Evidence, and the tagline for it and his Twitter handle states that “an ounce of data is worth a thousand pounds of opinion.” Jha says his only strongly held view is that “we should use data and empiricism to make decisions,” and he’s known for keeping bias and preconceived notions out of his research. “Ashish truly lets the evidence tell the story,” says Julia Adler-Milstein, PhD ’11, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan and a former student of Jha’s.

Jha has a split PubMed personality. He’s got researcher cred to spare as the co-author of dozens of the sorts of studies that home in on a relatively narrow question and build the knowledge base, result by result. But he also has a flair for analysis and a comparable number of review and opinion pieces on topical issues such as big data, hospital readmissions, and electronic health records (strongly for). His overarching concern is health care quality and patient safety.

Jha has a split PubMed personality. He’s got researcher cred to spare as the co-author of dozens of the sorts of studies that home in on a relatively narrow question and build the knowledge base, result by result. But he also has a flair for analysis and a comparable number of review and opinion pieces on topical issues such as big data, hospital readmissions, and electronic health records (strongly for). His overarching concern is health care quality and patient safety.

In that regard, Jha has shoulders at the School on which to stand. Lucian Leape, an adjunct professor in health policy and management, and other faculty pioneered the science of documenting medical errors, revealing how common these mistakes are, yet how infrequently they result in lawsuits.

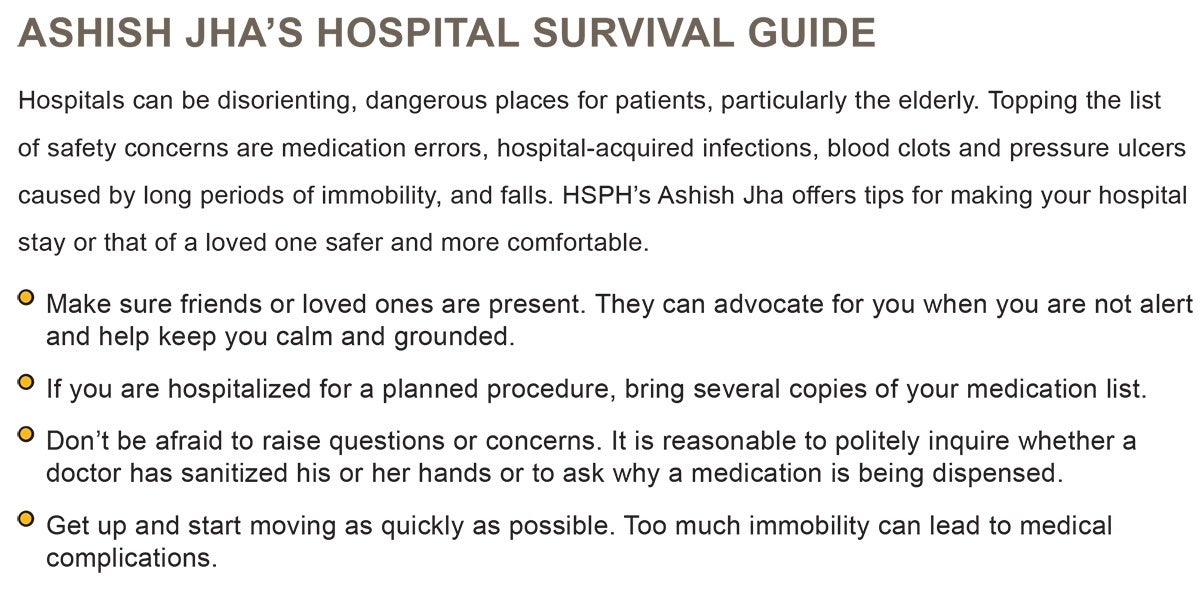

Jha had a front-row seat on the issue during his father’s hospitalization for what turned out to be a transient ischemic attack. Fortunately, his father was not harmed, but Jha witnessed three serious errors in his care, including his father receiving a medication intended for another patient.

Jha sees patient safety through the lens of systems analysis and through his own experience as a physician. He advocates the adoption of electronic health records. “I’ve practiced in paper-based systems, and I’ve practiced in electronic systems. I’m a much better doctor when I am practicing in an electronic system.”

He also supports financial incentives that put real money at stake to drive improvements in quality. Jha coauthored a study published earlier this year showing that the size of compensation packages for the CEOs of nonprofit hospitals are correlated with technology improvement and patient satisfaction scores, but not with patient outcomes or community benefit. “Doctors and nurses don’t practice in a vacuum—they practice in systems. And how a health care system sets up your doctor and nurse to be able to do the right thing is determined not by what’s going on in the clinic or the hospital room, but in the boardroom and the CEO’s suite.”

Jha believes that CEO pay should, in large part, hinge on quality improvement and patient safety. He further argues that as much as 15 or even 20 percent of hospital revenues should be at stake, to motivate a health care organization’s leadership to incorporate quality and safety into day-to-day practice.

Jha even floats the idea of letting patients wield financial clout. Instead of relying on surveys and satisfaction scores, how about giving patients say-so over how much is paid for their care—up to 30 percent of the bill?

“That’s Ashish for you,” says Leah Binder, president and CEO of the Leapfrog Group, an employer-financed organization that grades hospitals. “Always, always outside the box.”

Trust the messenger

It’s a safe bet that some of Jha’s message would not be received so kindly if the messenger weren’t so engaging. He smiles easily and laughs, sometimes at himself. Adler-Milstein describes her former teacher as the “most socially adept person I have ever met.” Many people in health policy circles principally think about what they have to say, notes Mark Miller, executive director of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which advises Congress on Medicare policies. Jha stands out because he listens.

Given his social grace, it makes sense that Jha thrives in the chatosphere of social media. His Twitter handle, @ashishkjha, has more than 4,000 followers—hardly Bieberian, but impressive for somebody who tweets about Medicare data sets and quality indicators. Jha has found that Twitter’s 140-character limit distills, rather than constrains, his thinking: “You need to get quickly to the point of what’s important, why people should read this. It forces clarity.” He started his blog in 2012 because he wanted to make unnecessarily confusing health care policy issues intelligible for a wider audience.

Most of Jha’s posts are his pithy gloss on health care policy doings and research (including his own). But he sometimes dips into personal experience. He told the world not only about his father’s hospitalization, but also about his experience last summer as an emergency room patient, after he fell while rollerblading and dislocated his left shoulder. The pain was excruciating but went untreated for too long, he recalls, with some of the staff more concerned with securing his insurance information than easing his suffering.

The cost of complacency

Health care quality is not just a rich-world problem, and Jha cites research showing that between 20 and 30 million years of healthy life are lost each year globally because of injuries from hospital care. Numbers like that mean unsafe hospitals should be framed as a major public health threat, he says. Having established the Harvard Initiative on Global Health Quality, he is partnering with the Global Health Delivery Project, co-founded by Paul Farmer, and will be collaborating with Indian health officials to improve the quality of health care there. This spring, Jha is teaching an EdX course on improving global health care. [Sign up for it at http://bit.ly/ph555x]

No one would ever say they are against improving the quality of health care. But Jha points out that there are entrenched interests in any health care system— people and institutions who like and depend upon the status quo. He counters that the cost of not doing more, of merely working around the edges of quality-of-care issues, is too high.

“We’re not going to solve these problems without evidence, new knowledge, new insights. That’s what’s so exciting about working on health care issues right now: It’s a chance to craft solutions with real-life impacts—a chance to save lives.”

Peter Wehrwein is a Boston-based journalist and editor specializing in health care and science.

Photos: Kent Dayton / HSPH; ©Bailey-Cooper Photography 3 / Alamy; ©moodboard / Alamy

Download a PDF of The provocative pragmatist