For immediate release: December 23, 2014

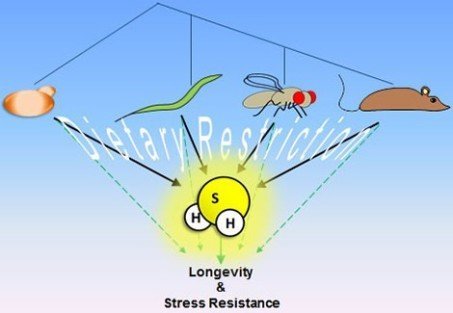

Boston, MA — A new study led by Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) researchers identifies a key molecular mechanism behind the health benefits of dietary restriction, or reduced food intake without malnutrition. Also known as calorie restriction, dietary restriction is best known for its ability to slow aging in laboratory animals. The findings here show that restricting two amino acids, methionine and cysteine, results in increased hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production and protection against ischemia reperfusion injury, damage to tissue that occurs following the interruption of blood flow as during organ transplantation and stroke. Increased H2S production upon dietary restriction was also associated with lifespan extension in worms, flies, and yeast.

Although H2S gas is extremely toxic in high amounts, low levels present in naturally occurring sulfur springs have long been associated with health benefits. Mammalian cells also produce low levels of H2S, but this is the first time that this molecule has been linked directly to the health benefits of dietary restriction.

“This finding suggests that H2S is one of the key molecules responsible for the benefits of dietary restriction in mammals and lower organisms as well,” said senior author James Mitchell, associate professor of genetics and complex diseases. “While more experiments are required to understand how H2S exerts its beneficial effects, it does give us a new perspective on which molecular players to target therapeutically in our efforts to combat human disease and aging.”

The study appears online December 23, 2014 in Cell. Watch a video that explains the findings.

Dietary restriction is a type of intervention that can include reduced overall food intake, decreased consumption of particular macronutrients such as protein, or intermittent bouts of fasting. It is known to have beneficial health effects, including protection from tissue injury and improved metabolism. It has also been shown to extend the lifespan of multiple model organisms, ranging from yeast to primates. The molecular explanations for these effects are not completely understood, but were thought to require protective antioxidant responses activated by the mild oxidative stress caused by dietary restriction itself.

First author Christopher Hine, research fellow in the Department of Molecular Metabolism, and colleagues demonstrated that one week of dietary restriction increased antioxidant responses and protected mice from liver ischemia reperfusion injury, but surprisingly, this protective effect was intact even in animals that could not mount such an antioxidant response. Instead, the researchers found that the protection required increased production of H2S, which occurred upon reduction of dietary intake of the two sulfur-containing amino acids, methionine and cysteine. When the diet was supplemented with these two amino acids, increased H2S production and dietary restriction benefits were both lost.

The investigators also found that genes involved in H2S production were also required for longevity benefits of dietary restriction in other organisms, including yeast, worms, and flies.

“These findings give us a better understanding of how dietary interventions extend lifespan and protect against injury. More immediately, they could have important implications for what to eat and not to eat before a planned acute stress like surgery, when the risk of ischemic injury can be relatively high,” said Hine.

Other Harvard School of Public Health authors include Eylul Harputlugil, Lear Brace, Humberto Trevino-Villarreal, Pedro Mejia, Yue Zhang, and William Mair.

The study was supported by grants from NIH (R01DK090629, R01AG036712) and the Glenn Foundation to James Mitchell. Christopher Hine was supported by T32CA0093823. Frank Madeo was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (LIPOTOX, I1000, P23490-B12, and P24381-B20). William Mair was supported by R01AG044346. Vadim Gladyshev was supported by R01AG021518. C. Keith Ozaki was supported by American Heart Association 12GRNT9510001 and 12GRNT1207025. Rui Wang was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“Endogenous Hydrogen Sulfide Production is Essential for Dietary Restriction Benefits,” Christopher Hine, Eylul Harputlugil, Yue Zhang, Christoph Ruckenstuhl, Byung Cheon Lee, Lear Brace, Alban Longchamp, Jose Trevino-Villarreal, Pedro Mejia, C. Keith Ozaki, Rui Wang, Vadim Gladyshev, Frank Madeo, William Mair, and James Mitchell, Cell, online December 23, 2014, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.048

Visit the HSPH website for the latest news, press releases and multimedia offerings.

For more information:

Todd Datz

tdatz@hsph.harvard.edu

617-432-8413

###

Harvard School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people’s lives—not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at HSPH teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.