Physician Burnout: A Public Health Crisis

Burnout among the nation’s physicians is so pervasive that a new report has deemed it a public health crisis. According to findings released in January, 78 percent of physicians say they experience some symptoms of professional burnout, such as exhaustion and diminished sense of personal accomplishment. Physicians experiencing burnout are more likely than their peers who aren’t to reduce their work hours or exit their profession, the report’s authors say. The researchers recommend appointing an executive-level chief wellness officer at every major health care organization, providing proactive mental health treatment and support for caregivers, and improving the efficiency of electronic health records. Co-author Ashish Jha, a Veterans Administration physician and dean for global strategy at the Harvard Chan School, says that physicians are spending more time on tasks that don’t directly benefit patients, which contributes to burnout.

Zhu Family Center for Global Cancer Prevention launches

The new Zhu Family Center for Global Cancer Prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health launched on February 4 with a symposium focused on cancer prevention and early detection. The center supports research and training and is guided by the belief that “all populations worldwide should benefit from state-of-the-art cancer-prevention strategies.”

Food System Transformation Needed for Human and Planetary Health

Nearly a billion people around the world are going hungry, and nearly 2 billion are undermining their health by eating too much of the wrong food. At the same time, food production is driving the destruction of natural resources that support human life. Halting these trends will take nothing short of a “Great Food Transformation,” according to a report from the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems, co-authored by Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard Chan School. The report, published online in January in The Lancet, calls for global cooperation and commitment to shift diets toward largely plant-based patterns, reduce food waste, and improve the sustainability of food production practices. “If we care about the world our children and grandchildren will live in, we need to transform our diets and the way we produce our food,” Willett says. “An immediate benefit will be improvements in our health and well-being.”

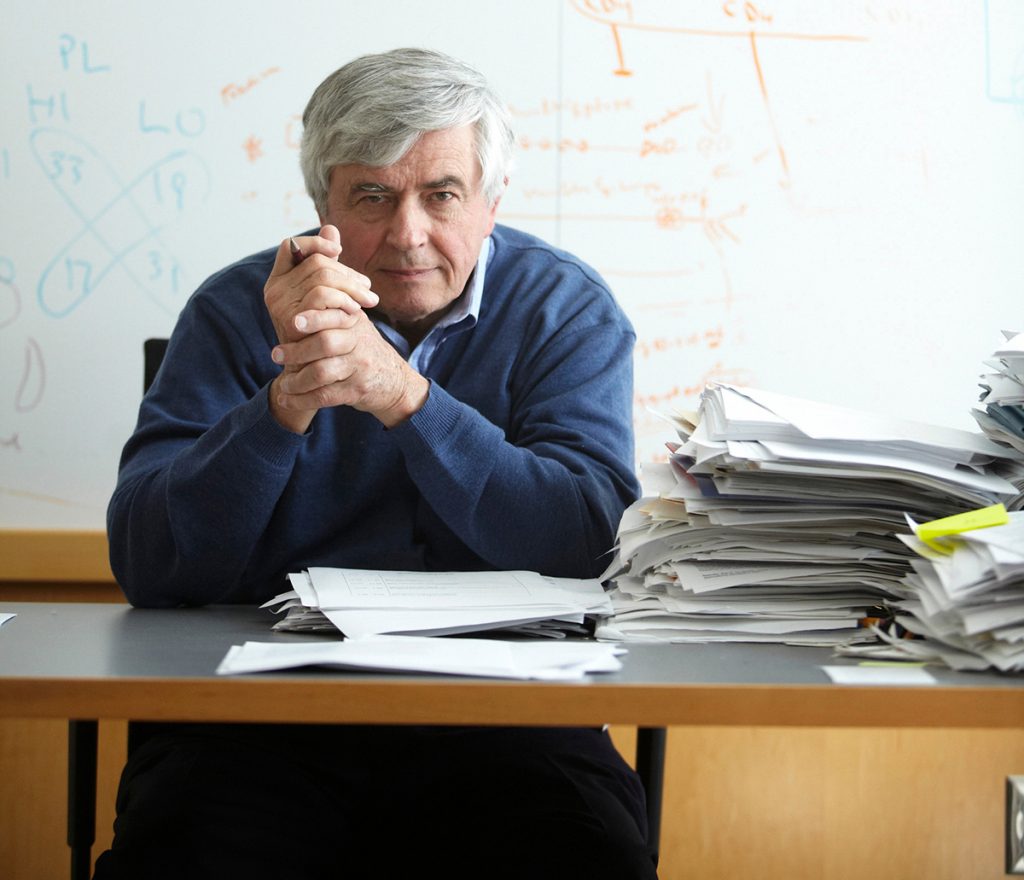

Pioneering AIDS Researcher Max Essex Honored

Researchers and other well-wishers from around the world, including Former President of Botswana Festus Mogae, gathered at the Harvard Chan School in November to celebrate trailblazing AIDS researcher Max Essex. The School and its AIDS Initiative hosted a scientific symposium to honor Essex, the Mary Woodard Lasker Professor of Health Sciences, as he prepares for retirement. Essex’s career spans more than four decades and is marked by many far-reaching achievements. In the early 1980s, he was among the first scientists to hypothesize that a retrovirus was the cause of AIDS. His research was instrumental in creating the first widely used HIV blood-screening test, and he helped discover a second AIDS virus, HIV-2, which is found mainly in West Africa. Essex also helped establish both the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health AIDS Initiative and the Botswana–Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership.

Marking 50th Anniversary of a Lifesaving Therapy

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT)—a mixture of water, sugar, and salt that is remarkably effective at rehydrating patients with cholera or other diarrheal diseases—is credited with saving tens of millions of lives worldwide. On November 19, a standing-room-only crowd at the Harvard Chan School gathered to mark the 50th anniversary of the first clinical trials of ORT, and to honor Richard Cash, senior lecturer on global health, who was instrumental in those trials and in bringing this low-tech, inexpensive therapy into worldwide use. Speaking at the event, Cash said that sometimes the simplest solution to a problem is the best one—and ORT is a perfect example.

Preparing for Pandemics with Simulations

Simulating a pandemic—in schools, housing complexes, or workplaces—could help people be better prepared if a real pandemic strikes. So says Pardis Sabeti, an expert in the genomics of infectious diseases, who co-authored a March 13 article in Wired about a simulated viral outbreak she helped run in 2018 at Florida’s SMA Prep. Sabeti, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard Chan School and a professor at Harvard University’s FAS Center for Systems Biology, partnered with Andres Colubri, a computational researcher in her lab, and teacher Todd Brown on an experiential learning module called Operation Outbreak.

Students were assigned various roles—as clinicians, epidemiologists, government officials, military, media, or the general population—and had to respond in real time to an “outbreak” that “spread” via Bluetooth from one student’s phone to the next. Sabeti and her partners now intend to create an open platform that teachers or researchers around the world could use to organize their own outbreak simulations. “Rapid response to a real-life pandemic is essential, and the role of community awareness and preparedness is critical,” Sabeti and her team wrote. “Why wait for a real-life pandemic to learn how to respond?”

Musician Esperanza Spalding Sings the Intersection of Art and Public Health

Using artistic tools like music and storytelling could be a powerful way to promote both healing and social justice. That was the message at a Harvard Chan School event that featured Esperanza Spalding, a Grammy-winning jazz bassist, vocalist, and composer, and a professor of practice in Harvard University’s Music Department. On February 27, before a rapt audience in Kresge cafeteria, Spalding and student panelists discussed the resonances between art, healing, and social justice. Spalding then sang and played bass on a few of her witty social-commentary-filled compositions.

Student panelists included Melanie Chitwood, SM ’19, Tariana Little, DrPH ’20, Ayesha McAdams-Mahmoud, SD ’19, and Katy Weinberg, MPH ’19. During the discussion, Spalding observed that art can provide a “cloak of anonymity” that makes it easier for people to share stories that are intimate, painful, or hopeful. “There is something about calling something art that makes it feel so much safer to share truths—and to receive other people’s truths,” she said.

Photos: ©Brian Stauffer, ©J.D. Levine Photography, gerenme/iStock, Kent Dayton