Finding offers insight into mechanisms of asthma, other diseases

August 11, 2015 — An unexpected new discovery—that, in people with asthma, the cells that line the airways in the lungs are unusually shaped and “scramble around like there’s a fire drill going on”—suggests intriguing new avenues both for basic biological research and for therapeutic interventions to fight the disease. The findings could also have important ramifications for research in other areas—notably, cancer—where the same kinds of cells play a major role.

Until now, scientists thought that epithelial cells—which line the lung’s airways as well as major cavities of the body and most organs—just sat there motionless like tiles covering the floor, or like cars jammed in traffic, said Jeffrey Fredberg, professor of bioengineering and physiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and one of the senior authors of the study, which was published online August 3, 2015 in Nature Materials. But the study showed that, in asthma, the opposite is true.

The physics of biology

The researchers decided to look at the detailed shape and movement of cells from the asthmatic airway because, according to Fredberg, a growing body of research is showing that physical forces change how cells form, grow, and behave. Given this knowledge—and the fact that no one knows what causes asthma, which afflicts more than 300 million people worldwide—it made sense to look at the shape and movement of epithelial cells, which many scientists think play a key role in the disease.

The study included lead authors Jin-Ah Park and Jae Hun Kim, research scientists in the Department of Environmental Health who study asthma, and Jeffrey M. Drazen, a pulmonologist and professor in the Department of Environmental Health, who studies “mechanotransduction” in asthma—how the bronchial constriction of asthma might trigger cell changes in the epithelium. The study also included mathematical physicists James Butler, senior lecturer on physiology in the Department of Environmental Health, and M. Lisa Manning and Max Bi at Syracuse University, as well as other colleagues from Harvard Chan School and other Harvard institutions.

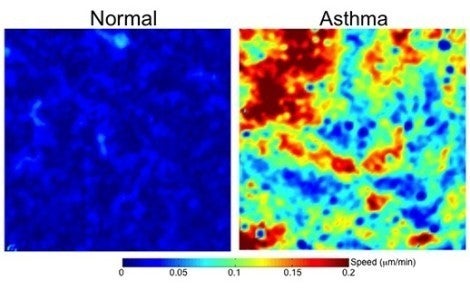

To analyze cell movement, the researchers took time-lapse images of epithelial cells. They also produced videos that show quite vividly the differences between normal cells and asthmatic cells. The videos, shown above, show that the normal cells are nearly pentagon-shaped and are jammed—they hardly move at all—while the asthmatic cells become more spindle shaped and are unjammed—they constantly move and swirl.

To analyze the mechanical forces at work, the researchers placed layers of epithelial cells—either from normal airways or asthmatic airways—on a soft gel surface that simulates the degree of stiffness of the lung. As the cells moved, their push-pull motion caused movement in the gel as well. This gel movement then enabled the researchers to infer the mechanical forces at work among the cells.

Next steps

Now that it’s known that epithelial cells in asthmatic airways are oddly shaped and are not jammed, scientists have to figure out why it’s happening—whether it’s asthma causing the cells to unjam, or if it’s the unjamming of these cells that causes asthma.

“It’s a very big question to figure out why this particular cell shape and movement is happening,” said Park. “We know that asthma is related to genes, environment, and the interaction between the two, but asthma remains poorly understood.”

Whatever the reason, knowing more about how these cells jam and unjam is important, said Fredberg, because epithelial cells play a prominent role not just in asthma, but in all processes involving cell growth and movement—including organ development, wound healing, and, importantly, cancer. The new findings about epithelial cells open the door to new possibilities for developing drugs to fight asthma as well as other diseases—and to new research questions.

“Trying to define how cells behave, how they exert forces on each other, and how that changes what they do are big open questions,” said Fredberg. “Researchers all over the world are looking more and more at these questions. It’s very exciting.”

— images courtesy Jeffrey Fredberg and Jin-Ah Park