Today, it’s conventional wisdom and a scientific truism that regular exercise is one of the healthiest habits around. But public health researchers weren’t always so certain that physical fitness was essential.

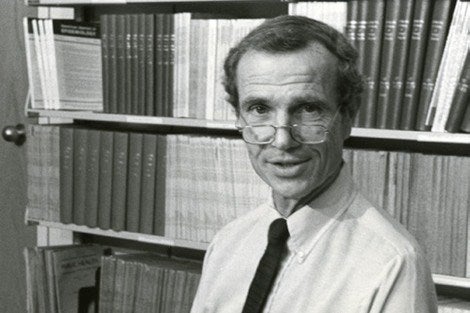

One of the first to scientifically document a link between physical activity and a longer, healthier life was Ralph Paffenbarger Jr., a pioneering epidemiologist who taught at HSPH from the 1960s to the 1990s. His attention-getting formula: Every hour of vigorous physical activity earns the exerciser an extra two or three hours of life.

When naysayers questioned whether that extra longevity consisted mostly of time spent exercising, the gentle yet tenacious researcher known as “Paff” to his colleagues observed that exercise not only “adds years to your life but life to your years.”

In 1960, Paffenbarger launched the College Alumni Health Study, which tracked the health and physical activity habits of 52,000 men who entered Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania between 1916 and 1950. Findings from the ongoing study have conclusively shown that men who exercised strenuously, burning 2,000 calories a week, lived longer than those who didn’t. Similar findings have been documented for women through the School’s long-running Nurses’ Health Study.

Paffenbarger took his findings to heart. He began running regularly in his 40s and became an avid marathoner. Paffenbarger remained an adjunct professor at the School until shortly before his death in 2007, at age 84.

Along with studies by Jeremy Morris of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Health, Paffenbarger’s research helped prompt changes in federal health recommendations and laid the groundwork for the modern fitness movement. He and Morris were jointly honored in 1996 with the first International Olympic Committee prize for sport science.