One tiny vial of blood contains a remarkable amount of genetic information about both the person from whom it was drawn and infectious agents like HIV circulating at the time of the needle prick. Because HIV mutates so quickly, having access to lots of samples to study is a valuable resource. “It’s a diamond for science,” said Sikhulile Moyo, Laboratory Manager at the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership (BHP). He was referring to the blood samples banked in the BHP freezers. “Specimens would be a more accurate term,” he corrected, “biological samples freely given to be processed for diagnosis or disease monitoring.”

One tiny vial of blood contains a remarkable amount of genetic information about both the person from whom it was drawn and infectious agents like HIV circulating at the time of the needle prick. Because HIV mutates so quickly, having access to lots of samples to study is a valuable resource. “It’s a diamond for science,” said Sikhulile Moyo, Laboratory Manager at the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership (BHP). He was referring to the blood samples banked in the BHP freezers. “Specimens would be a more accurate term,” he corrected, “biological samples freely given to be processed for diagnosis or disease monitoring.”

Over 1.5 million specimens are stored at the BHP headquarters in Gaborone, Botswana. Most are blood samples collected from tens of thousands of patients who have participated in BHP clinical trials over the past 20 years. Besides blood samples, the biorepository also includes specimens of hair, tissue, breast milk, and other bodily secretions.

The samples were collected for one reason: to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Botswana has one of the highest rates of HIV in the world with about 25% of adults infected. When the BHP was established in 1996, hospitals were overcrowded with very sick AIDS patients. There was no available treatment. Death, often agonizing, was the expected outcome.

In 2002, Botswana’s Ministry of Health launched a national antiretroviral program to provide free AIDS drugs to eligible citizens. The BHP played an important advisory role in planning, implementing, and monitoring the program. BHP clinical trials evaluated different drug regimens. Samples in the freezers come from those trials and others that followed. Today, with proper treatment, people living with HIV can expect to live a nearly normal life.

“What we have in the freezers is a history of the AIDS epidemic in Botswana,” said Moyo. There are blood samples from across the spectrum of the epidemic: from studies in the 1990s before the national program, to studies of treatment-naïve patients beginning drug regimens in the 2000s, to current studies of sero-converters—people recently infected with HIV.

Freezers

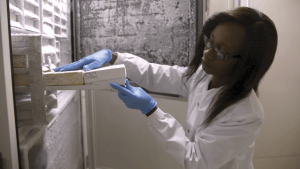

Though each sample is small in size, storing over a million samples becomes an issue. The BHP currently houses 70 freezers at headquarters. The majority of samples are kept in big freezers at close to -80°C, but viable cells used for immunological studies are stored in liquid nitrogen tanks at -140°C.

Each big freezer costs about $25,000, weighs 805 pounds, and can hold 24 steel racks of 2000 separate vials for a total of 48,000 samples. Each sample is bar-coded with a unique identifier. Descriptive information such as date and time of collection, study identifier, and specimen type is stored in an electronic inventory system that links to non-confidential demographics such as the age and sex of the participant. Samples are anonymized, meaning personal information such as name and address has been removed.

Because the samples are irreplaceable, efforts are taken to ensure their safety and integrity. The freezers are equipped with a temperature monitoring system connected to the internet, a mobile phone network, and a security company.

Freezers are expected to last ten years or longer, but disasters happen. If a freezer breaks down in the middle of the night, Moyo is awakened by a text and a phone call. If he’s not available, the security company works its way down a list of key staff contacts, with Dr. Joseph Makhema, CEO of the BHP, last on the list. Whoever responds must quickly move samples to a reserve freezer the BHP is required to have available at all times. When the power fails, a back-up generator keeps the freezers cold.

Shared Access

The stored samples are useful not only for the BHP, but for the global HIV/AIDS research community. When a study participant signs a consent form allowing the use of his or her sample for a specific research study, the participant has the option to sign a second consent form that allows the unused portion of the sample to be used for future HIV research.

In addition to BHP scientists and students, researchers from other countries can request samples for their HIV studies. If the study doesn’t overlap with work already underway and an ethics review board approves the study, samples will be packed and shipped, as they have been to South Africa, Great Britain, the U.S. and Canada.

“BHP acts as the custodian,” said Moyo. “This resource is open to other scientists as long as their research has been approved.” Though scientists have a reputation for being highly competitive, AIDS researchers have a history of working together. Most large HIV/AIDS studies are collaborative efforts across institutions and countries. “At BHP, we can try to chew the pie,” said Moyo, “but we definitely need others to help us chew the pie.”

“The samples are valuable because they represent a unique population of HIV-infected people at different stages of the epidemic,” said Max Essex, Chair of the Harvard AIDS Initiative and the Botswana Harvard Partnership. “These samples can be used to address a range of research questions, from how much the virus might have evolved over the last 20 years to how the epidemic itself has changed over that time.”

Photos by Dominic Chavez

To see original article, please click here.