By Chris Berdik | Winter 2021

Just before midnight on Sunday, March 22, 2020, President Donald Trump tweeted, “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF.”

America was just weeks into its coronavirus outbreak and was facing accelerating rates of infections and deaths. But the president’s all-caps alarm focused instead on the economic free fall triggered by both the rapidly spreading global health threat and federal and state efforts to slow the contagion by limiting gatherings, travel, and “nonessential” business activity. First-time unemployment claims had exploded to more than 3 million the previous week, and the stock market was plummeting. At a news conference the next day, Trump claimed that the health toll on Americans from the slow economy would exceed the damage from COVID-19.

“You have suicides over things like this when you have terrible economies,” he said. “You have death. Probably and—I mean, definitely would be in far greater numbers than the numbers that we’re talking about with regard to the virus.”

Public health experts quickly rejected the president’s assertion. Yet, the issue Trump raised was real. Recessions do increase suicides and the risk of other serious threats to mental and physical well-being, both immediate and long term.

Rather than a straightforward relationship, however, the research reveals a complicated set of interactions between the economy and health.

Counterintuitively, many studies have found some health benefits from economic slowdowns. Yet, there is also ample evidence that poverty is unhealthy. And one of the most consistent research findings is that the health hazards of recessions, much like the economic injuries they inflict, are uneven and fall heaviest on those who were already disadvantaged.

The intertwined vulnerabilities of health and economic disparities have perhaps never been more apparent than they are during the COVID-19 crisis. Untangling the current recession’s health impacts will be particularly challenging because of the massive and still-unfolding public health disaster at its heart, notes Benjamin Sommers, Huntley Quelch Professor of Health Care Economics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a primary care doctor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “It’s going to take a long time to sort all this out,” he says.

Nevertheless, public health researchers have begun this grim task. They hope to generate more findings on the reciprocal links between the economy and public health, inform responses to mitigate the damage, and help foster more health resiliency before the next shock inevitably arrives.

Hard times and healthier living

In the early 1920s, two Columbia University sociologists made a surprising discovery. Comparing America’s economic and mortality data from the previous half-century, William Ogburn and Dorothy Thomas found that death rates actually increased during boom years and fell during lean years. This counterintuitive finding was later replicated in studies of the Great Depression and then in subsequent research from multiple countries spanning the Great Recession of 2007–2009.

How could this apparent recessionary health boost be reconciled with the substantial evidence that poverty is bad for health? The most succinct explanation is that economic slowdowns cause a wide range of changes to our environment and personal behaviors that can either help or hurt our mental and physical well-being.

The prohealth impacts of recessions include a drop in traffic fatalities, as fewer commuters jam the roads. A 2016 Brookings Institute study found that a 1 percent increase in unemployment during the Great Recession reduced traffic deaths in the United States by 14 percent, equal to about 5,000 fewer traffic deaths per year.

Other studies indicate that people have more time to exercise during a slowdown, and that overall rates of drinking, smoking, and obesity decline. In other words, the apparent health benefits of a down economy may be due to a decline in the unhealthy behaviors we indulge in during boom times, according to Ellen Meara, professor of health economics and policy.

“When times are good, people are doing more of everything. They’re working more. They’re often eating and drinking more. They’re smoking more cigarettes,” says Meara. Indeed, some studies have shown that during recessions, tighter budgets may leave less discretionary money for booze and cigarettes.

If recessions change our behaviors, they also change our environment in ways that may lower disease risk. Specifically, a slower economy reduces emissions from vehicles and industry. COVID-19 restrictions and the subsequent slowdowns cleared skies from San Francisco to Beijing, reducing both nitrogen dioxide and the fine-particulate pollution known as PM2.5. As air pollution exposure decreases, so does the risk of heart disease, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indeed, some research has found that heart attack deaths drop during downturns and point to reduced air pollution as a likely cause.

It’s not all good news

While recessions may provide some population-wide health benefits, there’s also a rich history of research linking economic downturns to a range of negative health impacts. For instance, some studies of the Great Recession suggested that stressed-out people turned to unhealthy coping mechanisms, finding that fewer people tried to quit smoking and that tobacco use increased among folks whose income dropped below the poverty line. And while drinking may drop overall during recessions, binge drinking jumps, and drunken driving and alcohol dependence rates rise as more people lose their jobs.

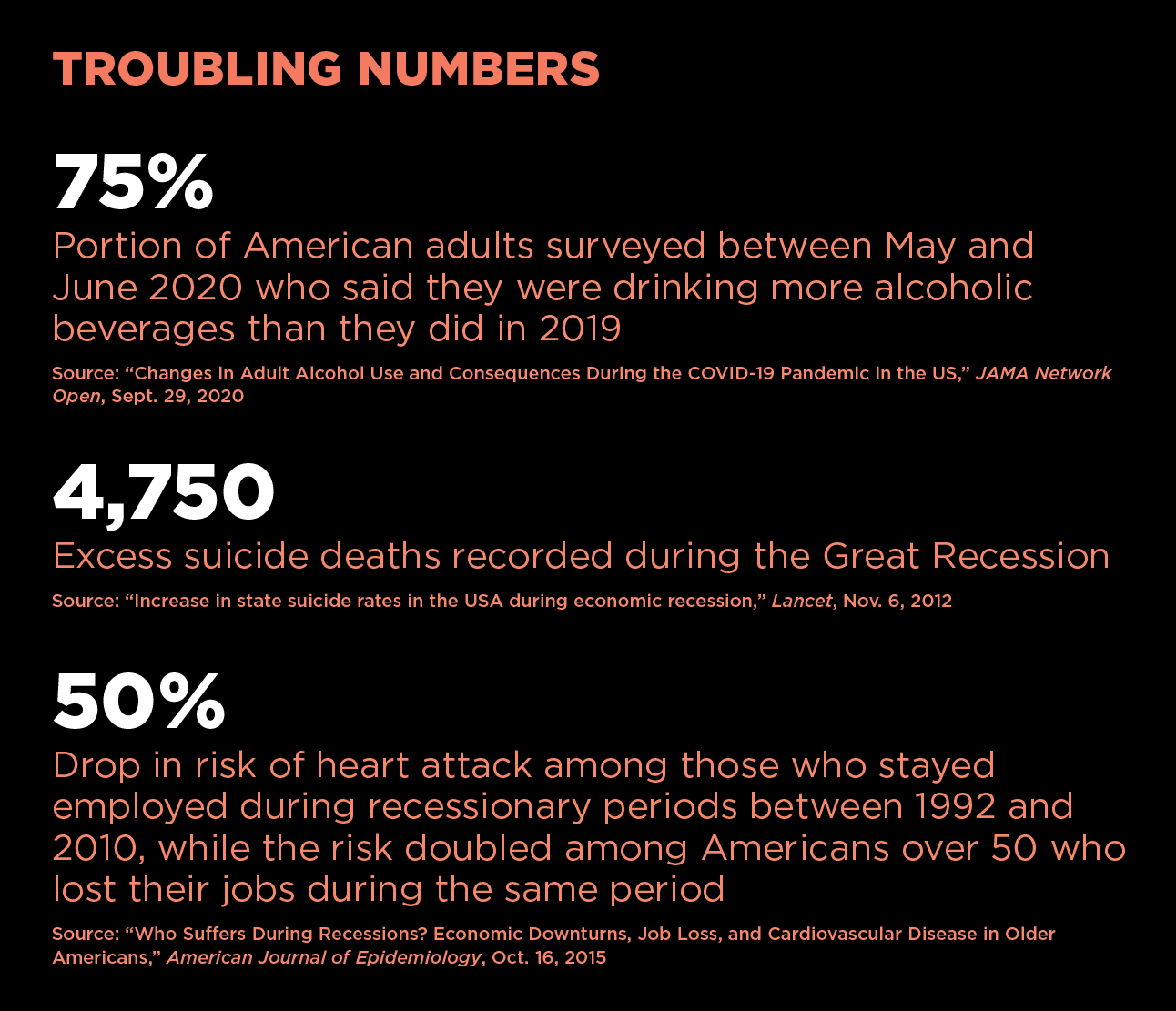

Alcohol sales from stores and online have been booming since March 2020, while sales at bars and restaurants dropped precipitously due to coronavirus restrictions that shut down many of these establishments. A September 2020 study published in JAMA Network Open reported that 75 percent of American adults surveyed in May and June of that year reported drinking more often than they did in 2019, and women reported an increase in heavy drinking (four or more drinks within a couple of hours).

Meanwhile, some studies find that cardiovascular disease and deaths increase among people hardest hit by a down economy, such as those who lose their jobs. Becoming unemployed in the current recession is particularly hazardous, says Katherine Baicker, dean and Emmett Dedmon Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago and adjunct professor of health policy and economics at the Harvard Chan School.

According to Baicker, the connection between employment and health insurance has always compounded the risks and stresses of losing a job. But when a deadly virus is raging out of control, the loss of employer-sponsored health insurance is much more ominous.

“The fact that you lose your job and potentially your access to health care in the middle of a public health crisis—that’s where the differential effect on health outcomes is likely to come in,” she says.

Ultimately, population-wide studies can tell you only so much about a recession’s health impacts, according to Clemens Noelke, a research scientist at the Institute for Child Youth and Family Policy at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Administration.

“It depends on what outcomes you study and what populations you study,” he says.

A few years ago, when Noelke was a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, he used survey data to track nearly 9,000 Americans age 50 or older from 1992 to 2010, focusing on the respondents’ employment status and heart health.

Noelke found that people who lost their jobs during recessions had more than double the risk of heart disease than those who remained employed. By contrast, recessions reduced the risk of heart trouble by 50 percent among those who kept their jobs, which most Americans do even in a harsh economy. The researchers surmised that people who stay employed during a slowdown may benefit from having reduced work hours and more time for sleep and exercise, while avoiding the major stressor of job loss.

Thus, to a large extent, the balance sheet of a recession’s health impacts depends on the lens used to examine them. In 2016, Sommers co-authored a study looking for links between American death rates by county and the unemployment numbers, poverty rates, and median household income between 1993 and 2012. The researchers hypothesized that the unemployment rate (a standard metric for such studies) was the weakest of the three proxies for economic hardship, because many people struggle financially even when they are employed, while others may be in financial distress but stop looking for work entirely—which would exclude them from standard unemployment measures.

Indeed, Sommers and his team found a “weak and inconsistent” relationship between unemployment and mortality, while the two other economic measures were far more predictive. When poverty rates rose or household income fell by one standard deviation, mortality went up (by 3.7 percent and 8.3 percent, respectively).

“When we analyzed the data in a couple different ways, we found what you’d expect,” says Sommers, “which is that when people are worse off economically, they’re sicker and more likely to die.”

Risks to mental health

When the economy tanks, stress, anxiety, and depression bubble up. The gloom afflicts those who lose their jobs, as well as many more who worry that their job may be next. A 2016 review of 183 studies found “consistent evidence” that down economies are linked with poorer mental well-being and higher rates of mental disorders, substance abuse, and suicidal behaviors.

In the United States, suicides have been on an upward trajectory since the turn of the 21st century, topping 48,000 in 2018, up from about 30,000 in 2000, according to the most recent data available from the National Institute of Mental Health. But the increase accelerated when times were tough, notably during the Great Recession. For example, a Lancet study estimated that between 2007 and 2010, there were 4,750 more suicides in the United States than previous trends would have predicted.

As with physical illness, the risks to mental well-being multiply along with a person’s financial troubles. A 2020 study in the American Journal of Epidemiology, using survey data from more than 34,000 Americans, found that suicidal thoughts or actions increased twentyfold among those who had experienced four types of financial strain in the previous 12 months—major debt, housing instability, unemployment, and low income—compared with those who had experienced none of these stressors.

Recently, Meara has been examining publicly available surveys on how the economic downturn is changing people’s mental health.

“They’ve been fascinating and disheartening,” she says. “They paint a picture that’s pretty consistent with other recessions, that people are reporting much higher symptoms of depression and anxiety.”

The U.S. Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey, for instance, shows how economic shocks add to the risk of anxiety and depression. Take the Pulse Survey ending November 9, 2020, which found that among people who had lost jobs or income, 49.7 percent said they had felt hopeless at least several days that week, and 53.6 percent said they’d felt uncontrollable worry, versus 33.9 and 36.5 percent, respectively, among people who had not experienced income loss.

The emerging published research on Americans’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic is alarming. One study compared self-reported depression symptoms (with scores corresponding to severity) from a 2017–2018 nationwide survey with one completed between March 31 and April 13, 2020. On the second survey, which finished just one month into America’s COVID-19 reckoning, the percentage of people reporting depression symptoms had risen at every level—jumping from 16.2 to 24.6 percent for mild symptoms and from 0.7 to 5.1 percent for severe. In addition, lower-income respondents were more than twice as likely to report these symptoms.

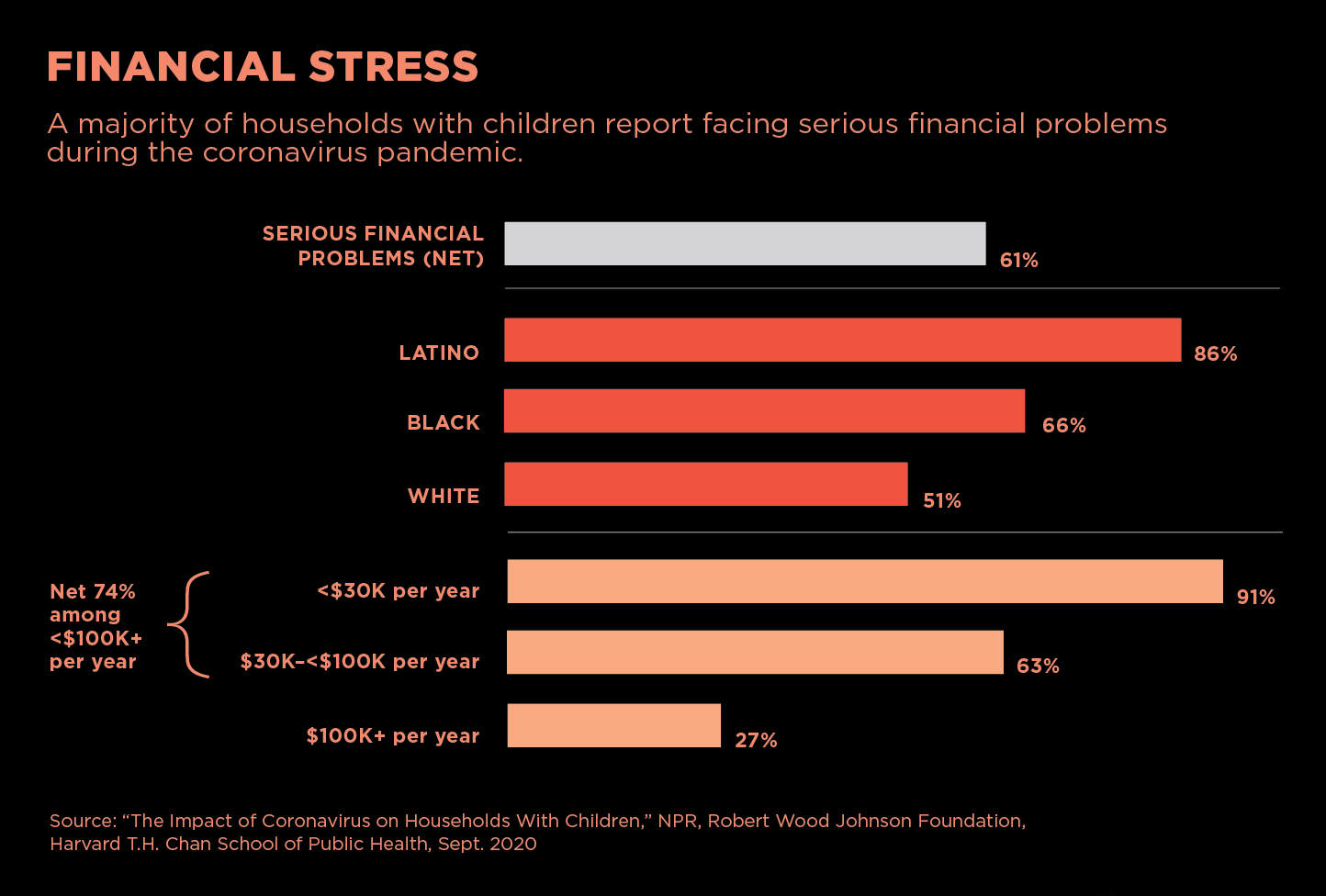

The economic losses during COVID-19 have been widespread, but they have hit people of color hardest. At the end of September 2020, the Harvard Chan School released national polling in collaboration with National Public Radio and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in which 61 percent of adults in households with children said they faced serious financial problems during the pandemic (including 86 percent of Latino and 66 percent of Black respondents, compared with 51 percent of whites).

Of course, the economic fallout is just one cause of stress and anxiety during the pandemic. People are naturally worried about themselves or a loved one getting sick. There is also anxiety about disruptions to children’s education and a vast, deep reservoir of grief for all the loss the pandemic has inflicted.

What’s more, the physical distancing and restrictions on gathering that define our downshifted COVID-19 economy also rob us of a powerful coping mechanism—each other.

“In disasters generally, we know that social support is really protective in terms of the mental health consequences,” says Karestan Koenen, professor of psychiatric epidemiology.

“The chronic nature of the stress has depleted everyone’s resources to some degree,” she says. “If it takes all your effort to keep yourself and your family going, then you don’t have much left to support other people.”

The evidence from one measure, charitable giving, is mixed. While donations to some charities, such as those tied to disaster relief, have increased during COVID-19, many others are hurting, especially those that relied on volunteers or in-person gatherings, such as concerts or galas, for fundraising.

For her part, Meara sees some reason for optimism. Despite the recent upticks in mental distress evident in her still-unfinished research, she has also observed another, more heartening pattern.

“What I think gets lost is that people are very resilient,” she says. “When you look at a lot of the symptoms of depression, even during times of crisis, you see a lot of recovery that happens just automatically, and those symptoms actually do tend to go down over time.”

Unequal and vulnerable

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “excess deaths” chart offers a bird’s-eye view of COVID-19 devastation in America. Before the pandemic, blue bars of weekly deaths track just below an orange curve of “expected deaths” that rises in winter and dips in summer (based on historic norms). Since March 2020, however, the blue bars have burst through the model’s expectations and set a new, higher curve of deaths that mirrors the waves of COVID-19 contagion.

Between March 1 and August 1, 2020, there were 225,530 excess deaths (20 percent above expected), and 150,541 of those deaths were officially attributed to the virus. What factors account for the remaining 74,989 (one-third) excess deaths?

Some are quite likely undercounted COVID-19 deaths, but the broader disruptions of the pandemic are probably also to blame, including the recession, which piles on stress and creates additional barriers to medical care.

Of course, the public health damage from COVID-19 extends beyond the fatality figures to millions who have fallen seriously ill. And both the virus and the recession have wreaked the most havoc among those who are already disadvantaged.

“I see this pattern with my patients,” says Sommers, “when they lose their jobs, when they’re worried about paying their rent, or they actually get evicted, or when they’re struggling to afford their medications or to afford healthy food. It is a real, multifaceted insult to people’s well-being.”

In a recently published study of COVID-19 data from Massachusetts, Sommers and other Harvard Chan School researchers found that several factors, including more crowded living conditions, more immigrants, and more people working in food-service jobs in a city or town predicted higher COVID-19 infection rates.

The researchers also found significant racial disparities in who got sick. A 10 percent increase in Black population between localities was associated with 312 more cases per 100,000 residents, and the same increase in an area’s Latino population was associated with 258 more cases per 100,000 residents. These findings mirror the CDC’s national figures, which show that African Americans and Latinos, respectively, have 2.6 and 2.8 times the COVID-19 infection rate of whites. Native Americans, meanwhile, have 3.5 times the COVID-19 infection rate of whites.

These health disparities have roots in economic inequality and structural racism that results in unequal labor conditions, wages, and protections, according to Natalia Linos, an epidemiologist and executive director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University. “The racial inequities about who’s getting sick have to do with who has the privilege to work remotely versus who has to be there in person,” she says.

Black and Latino deaths from COVID-19 didn’t simply outpace those of whites; they also skewed younger, so more of the deaths among people of color were working-age adults, according to a study led by Mary Bassett, director of the FXB Center and François-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights at the Harvard Chan School.

Indeed, in early March 2020, when America had suffered just a handful of COVID-19 deaths, Bassett and Linos co-authored a Washington Post op-ed warning that the U.S. could be more vulnerable to a widespread epidemic than other wealthy countries, due partly to the nation’s economic and racial inequities.

Among the disparities they cited were the millions of Americans without health insurance who might avoid testing and other critical medical care because of the financial burden, the millions of undocumented immigrants who would likewise avoid treatment fearing discrimination or deportation, and the 2 million incarcerated Americans whose health needs are often overlooked.

In addition, they wrote, “Americans, on average, are not as healthy as our peers in wealthy countries,” and the rates of preexisting conditions such as diabetes and chronic respiratory disease are highest among the poorest Americans. Unmentioned in the op-ed was the fact that nearly 34 million American workers had no paid sick leave, making them less likely to stay home if they became ill (including 49 percent of workers in the lowest income quartile, versus 8 percent in the highest quartile).

As of late November, the U.S. had the highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the world (fourth highest in cases per capita and eighth highest in deaths per capita among nations with at least 5 million people).

“We’re at about one-and-a-half million deaths globally, and the top three countries are the U.S., Brazil, and India, all of which have deeply unequal societies,” says Linos. “Is there something to be said about inequality and COVID-19?”

There is plenty of data about the expanding inequalities themselves. While most recessions take their biggest toll on already disadvantaged communities, the COVID-19 recession has been especially unequal. For instance, in the Great Recession, lower-paid employees suffered far more layoffs than higher-wage earners, but white-collar jobs in financial services and real estate also took a big hit and were actually slower than lower-paying sectors to rebound during the recovery.

By contrast, the current recession’s losses are concentrated in hospitality and other service industries with a high percentage of low-wage jobs held by people of color. These industries also employ a disproportionate number of women, who are simultaneously bearing the brunt of closed schools and vanishing child-care options. In the month of September 2020 alone, some 617,000 women (eight times the number of men) dropped out of the workforce, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

At the same time, wealthier Americans have been rapidly recovering from COVID-19’s economic disruption. By early summer of 2020, the job losses that higher-wage earners sustained in the first months of the pandemic had largely been reversed.

Reinforcing the safety net

It will take many years to fully assess the health ramifications of these job losses, according to Sara Bleich, professor of public health policy. Bleich studies economic and policy influences on food insecurity, which is linked to a host of health issues across the life span such as increased risk of birth defects, anemia, asthma, diabetes, and cognitive and behavioral problems.

Annual reports by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) show that Americans’ access to sufficient, nutritious food rises and falls along with their economic fortunes. By early November, the Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Surveys indicated that the number of adults reporting that their households sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat rose to 26 million, more than tripling the pre-COVID-19 baseline of nearly 8 million.

The biggest piece of the nutrition safety net, the $65 billion Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) was insufficient even in normal times, says Bleich, when its main purpose was to supplement the food budget of low-income households. From February to May 2020, SNAP participation increased 17 percent—three times faster than in any previous three-month period—and brought the number of Americans relying on food assistance to about 43 million.

“Now, we’re seeing massive job losses, so not only are the number of families relying on the program growing,” she notes, “but so are the needs of the families that were already relying on SNAP whose income has gone down or gone to zero. How do you make up that gap?”

Bleich points out that funneling federal dollars into SNAP not only improves public health but also stimulates the economy, with every $1 spent pumping up the GDP by $1.50, according to a 2019 USDA study.

“If you give money to low-income people, it quickly goes back out into the economy and spurs recovery,” she says. Bleich hopes awareness of SNAP’s benefits, combined with the expanding numbers of people who now depend on the program, will increase support for it among policymakers and the public.

In fact, the pandemic has prompted many states to make SNAP benefits easier to use. Since the start of the outbreak, the number of states allowing people to use SNAP online has skyrocketed from just two to 46 and the District of Columbia. The number of authorized online retailers has also increased from less than a handful to more than a dozen. After several months of delay, the most recent pandemic stimulus package passed as part of the fiscal year 2021 appropriations and temporarily increased the maximum SNAP benefit by 15 percent (or about $100 for a family of four each month). But given the well-documented inadequacy of the SNAP benefit, Bleich believes that a permanent increase is needed.

Overall, several studies find that broader social safety nets cushion the stress of economic downturns, while cutting these programs leads to worsening public health outcomes. Nevertheless, government spending decisions are always a contest of competing priorities, says Bleich.

“Lower-income people tend to have a weaker political base,” she says. “The reality is that the safety net serves such an important purpose in the lives of millions of Americans, but its advocates are usually not the loudest voices in the room.”

Both Bleich and Linos contend that a full recovery from COVID-19 and the current recession will need to meaningfully address structural inequalities and the health disparities that appear to be widening during the pandemic.

Linos hopes that the twin catastrophes of the pandemic and economic collapse have revealed the tight, reciprocal links between America’s health and economic well-being and the fragility that inequality can bring to both.

“I do think that it’s a chance to have those conversations, and to say that deep-rooted inequality in our country is a vulnerability,” she says. “This tragedy isn’t a one-time thing that is just a fluke. It will happen again, and with climate change and zoonotic diseases becoming much more frequent, we know that this is the kind of shock that we need to be better prepared for.”

Chris Berdik is a Boston-based science journalist.