Harvard Chan School symposium, part of Harvard Climate Action Week, offers tools, ideas from a global perspective

May 10, 2023 – The wide-ranging health impacts of climate change, including food insecurity, migration, war, and the spread of infectious diseases—and practical solutions to address these problems—were the focus of a half-day symposium hosted by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The May 8 event, titled Climate, Health & Equity: Toward a Sustainable Future, was part of the inaugural Harvard Climate Action Week, sponsored by the new Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability.

Speakers at the symposium, held at Harvard Business School’s Spangler Center, included community activists, state and federal administrators, and scientists.

“Climate change is not a distant abstract concept or threat,” said Harvard Chan School Dean Michelle Williams in opening remarks. “Climate change is harming our health, right here and right now. Climate change is deepening inequities, right here and right now. And we all know that we have the tools to tackle climate change, right here and right now.”

The symposium featured a brief video highlighting Harvard Chan School’s decades-long legacy of tackling the health impacts of climate change, such the landmark Six Cities Study, which led to a tightening of U.S. air pollution standards in the 1990s, and the founding of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (Harvard Chan C-CHANGE) in 2018.

On the climate change front lines

Kari Nadeau, John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies and chair of the Department of Environmental Health, moderated the event, which featured several panels. The first featured three community activists: Carolina Reyes, a community health care worker from Springfield, Mass.; Shweta Narayan, a global climate campaigner with the international nongovernmental organization Health Care Without Harm; and Passy Amayo Ogolla, program manager for the nonprofit Society for International Development.

Narayan, who lives in a small village in southern India, said she has seen temperature and rainfall changes affect local agriculture and disease spread. Reyes spoke about increasing rates of allergies and asthma in Springfield. And Ogolla described droughts in her community, and elsewhere in Africa, that have led to food insecurity, malnutrition, and people dying from hunger. “The challenges are dire, not just affecting health, but the entire livelihood of the community,” she said.

On a personal level, Ogolla has taken action to improve the situation by planting a fruit tree forest in her community to provide both shade and healthy food—and she has encouraged others to plant more trees as well. Reyes has worked to educate doctors, religious leaders, and families about climate change’s health impacts and the importance of keeping the environment safe and healthy for all. “We’re in 2023 and we’re still using gasoline,” she said. “Why are we still using harmful nail polish? Plastic bottles? We have to make it personal and make the government take it personally too.”

Governments must be accountable for setting policies aimed at limiting climate change, the activists agreed. Said Ogolla, “I strongly believe that prevention is better than cure. I would strongly call upon policymakers to look into their climate and sustainable energy policies and strategize toward implementing these now so that future generations can have a planet to look forward to. And not just any type of planet—a planet where people are healthy and living sustainably.”

Documenting food insecurity

Louise Ivers, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute and professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, moderated a panel on food insecurity, noting that it affects a quarter of a billion people worldwide. Panelists included Harvard Chan School’s Chris Golden, Abrania Marrero, and Jennifer Leaning.

Golden, assistant professor of nutrition and planetary health, spoke about his research on how climate change destabilizes food systems. Much of his work has focused on Madagascar, where he has assessed how impacts such as sea temperature rise and ocean acidification can lead to coral bleaching, threatening the ability of fisheries to reproduce and to provide seafood for Indigenous cultures and others living in the global South. As for solutions, Golden suggested using environmental data to create an early-warning system for communities and countries to predict where health impacts might occur. He also described his work creating artificial reefs in Madagascar to help rehabilitate fish stocks.

Marrero, a postdoctoral research fellow, discussed her studies of nutrition, small-scale farming, and climate resilience of island nations, particularly in Puerto Rico. She noted that although Puerto Ricans traditionally grew their own food, the situation changed in recent years to the point where, today, 85%-95% of the food in the country is imported—much of it highly processed and unhealthy. “This radically affects the health of people, of local economies, of livelihoods, of ecosystems,” Marrero said. Research she’s worked on has shown that people who eat locally produced foods have better nutritional status. She also noted that there is much to be learned from small-scale food producers about healthy land stewardship, which can both bolster livelihoods and reduce food insecurity. Studying how small producers operate “can really help us think about what are the practices that we can learn from on a larger scale,” she said.

Leaning, senior research fellow at the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health & Human Rights, talked about how climate change-driven drought led to migration and conflict in Syria, fueling that nation’s ongoing civil war. She also discussed the problem of dangerous heat in India, noting that the government there is working to form heat action plans so that people have adequate shelter and water during life-threatening heatwaves.

A focus on policy

State and federal actions to mitigate the health impacts of climate change were the focus of two panels. One featured Melissa Hoffer, who was appointed Massachusetts’s first-ever Climate Chief earlier this year. Having a state climate chief is crucial to ensure that climate considerations are “in the bones” of all the other state agencies, Hoffer said. She has been working on a variety of fronts, such as increasing the use of electric vehicles and promoting environmental justice.

“We know what we need to do,” said Hoffer. “We have to stop using dirty fossil fuels. We need to stop investing in all the institutions that support the development and production of these fuels. We have to start baking in a social cost of carbon.”

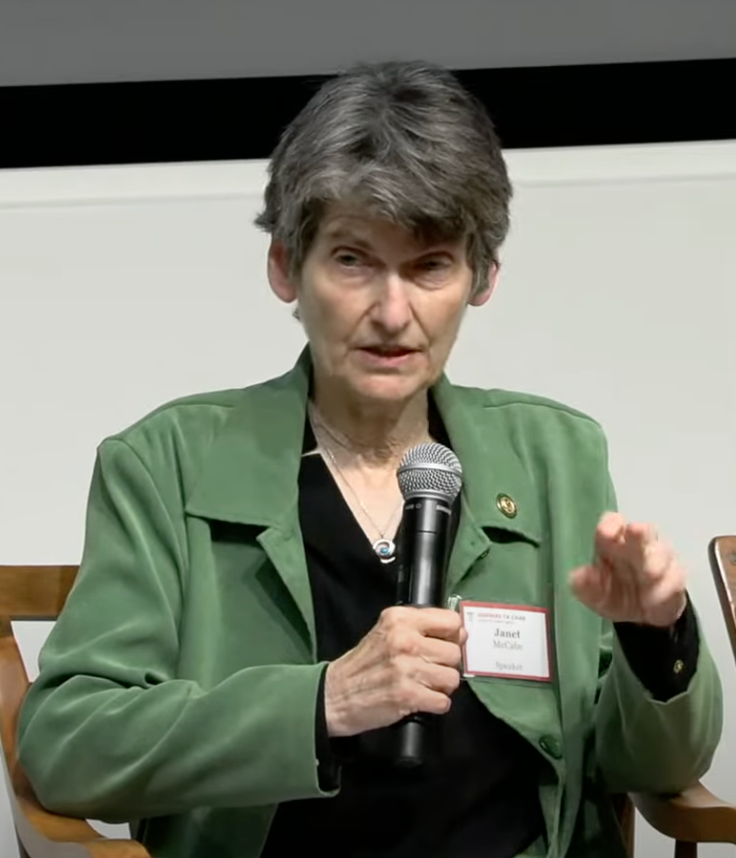

Janet McCabe, deputy administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, spoke with Harvard Chan School’s Tamarra James-Todd, Mark and Catherine Winkler Associate Professor of Environmental Reproductive Epidemiology, about federal policies aimed at reining in climate change. “This is an incredible time at the EPA,” said McCabe, citing a new federal rule that will massively reduce air pollutants from heavy-duty trucks, a proposed rule that would institute the toughest-ever emissions caps on all cars and trucks, and an upcoming proposal on limiting fossil fuel-fired power plant emissions. These rules, together with rules being put in place by other federal agencies, put the nation on target to meet President Biden’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions by roughly 50% by 2030, said McCabe.

Climate change and infectious diseases

Increases in malaria and diarrheal diseases, even another pandemic—such are the infectious disease threats posed by climate change, according to three experts from Harvard Chan School who spoke during a final panel.

Aaron Bernstein, C-CHANGE interim director and soon-to-be director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Environmental Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, said that as temperatures increase, insects move—along with the diseases they carry. For example, he said, tick-driven Lyme disease is now showing up in Canada for the first time, and avian malaria, transmitted by mosquitoes, is impacting birds at higher altitudes than ever in the mountains of Hawaii. Marcia Castro, Andelot Professor of Demography, noted that deforestation in Brazil puts people in closer contact with wildlife, raising the risks of zoonoses—diseases that jump from animals to humans. And Caroline Buckee, professor of epidemiology, talked about how extreme weather events lead poor people living off the land to become “climate refugees,” moving to cities to find work. “If you were going to design a perfect situation for a global pandemic, you put them in crowded places and connect them by global travel,” she said. “That’s exactly what we have.”

The researchers stressed the importance of gathering adequate data to document climate-driven impacts on the spread of disease, and for governments to regulate these impacts. Buckee added that it’s key for researchers in the global North to learn lessons from partners in the global South, who have experience in handling extreme heat and natural disasters. Bangladesh, for example, does a great job of responding to cyclones because they hit the country regularly. Creating meaningful academic partnerships in countries like Bangladesh could help in developing strategies for the future, she said.

Climate resiliency

Keynote speaker for the symposium was environmentalist and civil servant Heather McTeer Toney, who previously served as the first woman, the first African American, and the youngest-ever mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, where she fought to clean up the community’s tap water. She went on to serve as regional administrator for the EPA’s Southeast region and as a leader in the Mom’s Clean Air Force. Currently she is vice president for community engagement for the Environmental Defense Fund and executive director of Beyond Petrochemicals, a campaign launched by Michael Bloomberg to stop expansion of petrochemical and plastic pollution in the U.S.

Communities facing environmental injustice across the U.S. have been resilient in the face of climate change effects “because it’s what we have to do,” Toney said. In addition to dealing with polluted air, water, and land, these communities also face a host of other issues, such as unfair healthcare and education systems, police brutality, food disparities, and failing infrastructure. Efforts to address the health impacts of climate change, she said, must take all of these factors into account. “We have to connect the dots,” she said.

Feature photo courtesy Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability

For stories of climate hope and action, subscribe to The Climate Optimist newsletter.