November 8, 2016 – In recent years, a growing body of evidence has suggested that phthalates—synthetic chemicals used in scores of products ranging from vinyl flooring to food packaging to medical tubing to cosmetics—can cause reproductive harms. Now, two new studies from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have revealed that these hormone-disrupting chemicals may increase both the risk of miscarriage and risk factors for gestational diabetes.

Much of the evidence about phthalates’ potential harm comes from animal studies; less is known about their impact in humans. The results of these two studies are important because pregnancy loss is prevalent—about 31% of all conceptions end in miscarriage—and the incidence of gestational diabetes has tripled over the past two decades, now occurring in 7% of all pregnancies worldwide.

The problem with plastics

One study followed a group of 256 women at Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center from 2004 to 2014 who were undergoing medically assisted reproduction, such as in-vitro fertilization. The researchers measured concentrations of 11 phthalate metabolites in the women’s urine around the time of conception. Women with the highest concentrations of a type of phthalate called di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, or DEHP, were 60% more likely to lose a pregnancy prior to 20 weeks than those with the lowest concentrations, the study found.

Lead author Carmen Messerlian, a research fellow in Harvard Chan School’s Department of Environmental Health, called the findings compelling, noting that this was the first study to examine how phthalate exposure may affect pregnancies in their earliest stages among couples who have difficulty becoming pregnant. Russ Hauser, Frederick Lee Hisaw Professor of Reproductive Physiology and acting chair of the Department of Environmental Health, was senior author, and was also a co-author on the second study.

DEHP is a plasticizer—it helps make polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics flexible and durable. It’s found in items such as medical equipment, building materials, shower curtains, plastic window blinds, and headphone cords. PVC plastics with DEHP are also used in manufacturing, such as in tubing or conveyer belts in food processing plants. Because DEHP is only loosely chemically bonded in plastic products, it can easily leach out, and people can be exposed to DEHP through air, water, food, intravenous fluids, or skin contact with DEHP-containing plastics.

Some cosmetics, fragrances may pose risk

A second study followed a separate group of 350 pregnant women who delivered their babies at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston from 2006 to 2008. Following the women throughout their pregnancies, and taking urine samples at early, mid-, and late pregnancy, the researchers found that those with the greatest urinary concentrations of monoethyl phthalate (MEP)—a type of phthalate commonly found in personal care products such as fragrances and cosmetics—had twice the risk of excessive weight gain during pregnancy than those with the lowest concentrations. Those with the highest mid-pregnancy MEP concentrations also had a seven-fold higher odds of impaired glucose tolerance (higher-than-normal blood glucose levels) in mid-pregnancy than women with the lowest concentrations, although these findings need to be replicated in larger studies, said lead author Tamarra James-Todd, Mark and Catherine Winkler Assistant Professor of Environmental Reproductive and Perinatal Epidemiology.

Both excessive weight gain and impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy are risk factors for gestational diabetes. And approximately 50% of women who develop gestational diabetes go on to develop type 2 diabetes in the years following pregnancy, said James-Todd.

“We know that improving a woman’s lifestyle through a healthier diet can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes,” she said. “The question is whether we can also reduce the risk by reducing exposures to the highly prevalent phthalates found in cosmetics and fragrances, which can be absorbed through the skin or inhaled.”

Avoiding exposure

“Phthalates are ubiquitous,” Messerlian said. “And while they don’t bioaccumulate—they are not stored in our bodies for a long time—we do have repeated daily exposure to them.”

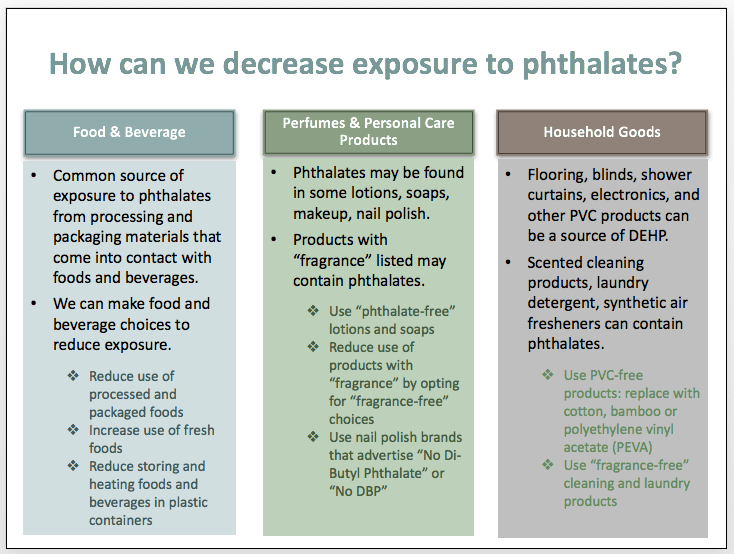

There are some steps people can take to limit their exposure to these chemicals, said Messerlian and James-Todd. People can reduce consumption of processed and packaged foods which may contain phthalates from contact with food processing or packaging materials. People can also buy non-PVC shower curtains, non-PVC window blinds (bamboo or cotton instead of plastic), and natural linoleum flooring instead of vinyl.

Since phthalates are used as an ingredient in some scents found in creams, lotions, sprays, and other personal care products, one way to reduce exposure is to avoid products that list “fragrance” or “parfum” as an ingredient and to instead use unscented products that say “fragrance free” or “phthalate-free.”

Additional studies are needed to confirm the potential impact of phthalates on miscarriage and on risk factors for gestational diabetes, said Messerlian and James-Todd. More studies are also needed to explore whether changing the types of products we choose will have real effects on our health.

Additional studies are needed to confirm the potential impact of phthalates on miscarriage and on risk factors for gestational diabetes, said Messerlian and James-Todd. More studies are also needed to explore whether changing the types of products we choose will have real effects on our health.

In the meantime, since phthalates are in so many products and there is only so much consumers can do to avoid them, “We need to rely on better regulations surrounding the use of these chemicals in consumer products, as well as the development of safer alternatives,” said James-Todd.

photo: iStock